Come summer, Indians engage in a unique mango one-upmanship: Alponso or Langda; Ratnagiri or Devgarh Alphonso; Gujarati Kesar or Banarsi Chausa. If you ask me, this kind of mango tribalism is trite. The mango season is short. Eat whatever you can find.

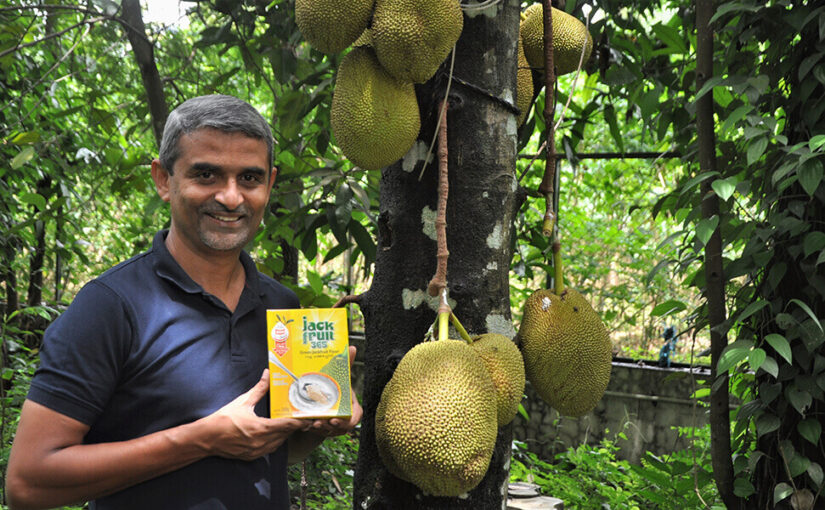

But this is also the season of jackfruit, a fruit far more complex in flavour, and a veritable super food that Indians in its native land love to despise. Jackfruit of course has an exalted status in traditional Tamil literature, alongside banana and mango. Jackfruit can grow prolifically anywhere in peninsular India and the mid-to-lower Gangetic belt, pretty much.

I’ll share a couple of The Plate’s jackfruit stories here.

Follow ThePlate.in to understand India from farm to plate!

X: https://twitter.com/thePlateIndia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theplateindia/

Recently I read a piece on Indian cuisine from a “woke” perspective,

Recently I read a piece on Indian cuisine from a “woke” perspective,