Script for the Youtube Video:

Script for the Youtube Video:

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode of Browncast, Gaurav and KJ talk to Indian Mango and Nitesh about the Landslide in the Maharashtra assembly elections 2024.

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this chat our 2 Resident US citizens and 2 Indians analyze US elections and its implications

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode KJ and Gaurav talk to a Marathi commentator from Marathwada-Vidarbha region about upcoming MH elections and the role of Maratha politics in it.

In the run up to Indian parliamentary elections in 2024, there is excitement in some sections of social media about “freemarket” ideas espoused by C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) and the Swantantra Party he helped found in 1959.

Sharing a piece here I wrote on Rajaji’s ideological relevance in contemporary politics. This was written after visiting and reporting from the many institutions he built pre and post 1947 for the now defunct Pragati Magazine in 2018.

You can follow me here.

And the food-and-agriculture-focussed independent media platform called the ThePlate.in I run.

Here goes…

Rajaji: Our Forgotten Hero

Among the leaders in the front ranks of the freedom movement, and those counted as the makers of modern India, Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) is perhaps the man most forgotten. Gandhi is the ‘Father of the nation’; the very existence of India as a modern democracy, and lately all its faults—from clogged drains to currency fluctuation—are credited to Jawaharlal Nehru’s side of the ledger; the race to usurp Vallabhbhai Patel’s legacy has given India a Guinness record for the world’s tallest statue; Bhimrao Ambedkar is not only a Moses-like lawgiver who framed the constitution but also the messiah of marginalized; Maulana Azad, now firmly located in Indian-Muslim politics, finds an occasional ode to his prescience about the fallacy of Pakistan and subsequent fate of subcontinental Muslims. Rajaji is less lucky than Azad. Continue reading Rajaji: Our forgotten hero

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

Modi does the unthinkable – goes to polls with a non-populist (revdi-free) budget

At the start of this year, I had written about Modi’s excellent economic stewardship during his second term amidst a period of extreme economic turbulence globally – a once-in-a-century pandemic followed by a major war which roiled energy markets and rapid rate hikes in the West to combat inflation (Modi’s fiscal masterclass). I had noted then that Modi:

“has achieved the near impossible of following a disciplined fiscal policy while not just maintaining his political capital, actually expanding it”

But I had fully expected that he would open up the purse strings during the election year budget this February notwithstanding his public remonstrations against the growing revdi (freebies) culture. And for good reasons. One, Modi had gone in for a ‘revdi’ at the end of his first term in 2019 (the cash transfer scheme for 120 million farmers). And the economic scenario in 2024 was decidedly more mixed compared to 2019 with greater level of economic distress among the poor. Two, recent state elections had seen parties winning based on extremely aggressive freebie promises. For example, Congress won handsomely in Karnataka last year with promises of a slew of freebies (or welfare programs if you like) amounting to more than 2% of the state’s GDP. So I must not have been the only person who was stunned to see that Modi had decided that the normal rules of politics does not apply to him. And as of today, his judgment appears to be spot-on because the only debate about the 2024 elections appears to be what his margin of victory will be. The reasons for this – the so-called “akshat-wave” after the Ram mandir inauguration, the opposition being in absolute shambles, the ever-increasing political stature of Modi – calls for a separate discussion. In this post, I peer into the future and see what Modi’s fiscal statesmanship could potentially mean for the country.

A 10-year long fiscal tapasya….

For reasons that are not entirely clear, fiscal conservatism has been an article of faith for Modi throughout his career as an administrator. He has held on to it steadfastly during his entire 10 years as the the Prime Minister. For anyone familiar with Indian politics, it is easy to appreciate how challenging it can be to stick to fiscal discipline even during times of buoyant revenues. This makes his unrelenting fiscal focus all the more remarkable considering that for most of his tenure, he has been hemmed in by weak tax revenues. Therefore, to call Modi’s 10 year long commitment to financial discipline as a tapasya (penance) would not be out of place.

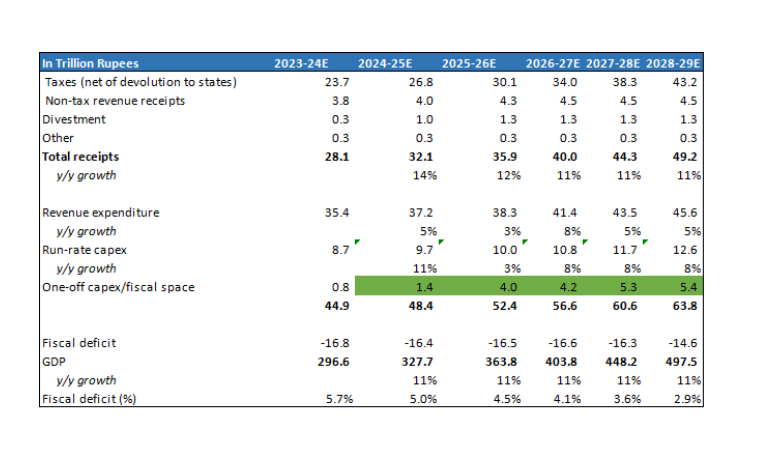

…might finally yield a Rs.20T (~$50bn) -sized fruit during Modi-3

And Modi is on the cusp of reaping the fruits of that tapasya in his third term. Barring unexpected shocks – electoral and economic – he could be presiding over a period where the economy has sizeable fiscal resources to pursue its socio-economic goals; a rare event in independent India’s economic history. Underpinned by a solid cyclical recovery in the economy and strong buoyancy in tax collections (direct taxes likely grew at 20% in 2023-24, twice the pace of nominal GDP growth), Modi-3 is not only placed very comfortably to meets its 2025-26 fiscal deficit target of 4.5% (vs. 5.8% in 2023-24), it will also have its disposal, up to Rs.4 trillion of fiscal space during 2025-26 for spending on new programs or projects (or >1% of GDP) after meeting its regular revenue and capital expenditure obligations. That is the base case which assumes direct taxes grow at 15% annually. In a bull case of direct taxes continuing to grow at 20%, the above figure could be as high as Rs. 5.5 trillion. Further, this figure will continue to swell with each succeeding year as the economy expands and revenue growth outpaces the growth in base expenditure. During Modi’s third term, I estimate that the central government will have up to Rs.20 trillion of aggregate fiscal space for new programs/projects. Also, note that many of the programs of the central government include contribution from the states, which means the total fiscal resources available could be well higher than Rs. 20 trillion.

(For those interested in the math behind the above numbers, I discuss the same at the end of the post) .

Potentially transformative, but availability of funds is not enough

What can one do with an annual budget of Rs.4 trillion? Well, for perspective, the Jal Jeevan Mission which was initiated in Modi’s second term with an annual budget outlay of Rs.0.7T (Rs.3.5T over 5 years, 60% funded by centre) will have provided tap water connections to 160 million households by end of 2024 (110 million connections provided as of April 2024). No commentary required on how transformative this project has been for the 100s of millions of beneficiaries.

In the first two terms, Modi’s focus was primarily on building physical infrastcucture – road building under Gadkari has been an unqualified success while in case of Railways, huge investments have been made, it is still a work-in-progress with mixed results so far. Even welfare schemes had a physical asset bias – from toilets to piped water to housing. While the government deserves a lot of credit for strong execution, it has to be underlined that these are relatively low-hanging fruits from a governance perspective. As the priority areas inevitably shift from road and railways to more complex ones, quality of policymaking, human capital and management will be the key drivers of outcomes, and not just availability of funds. To wit, it is way more difficult to develop 20 high quality IITs or a few hundred Kendriya Vidyalayas compared to building 100K kms of roads. Or just throwing around money into PLIs will not deliver a successful industrial policy.

An opportunity for Modi to cement his legacy – a wide range of focus areas to choose from

What areas Modi will prioritize with the Rs.4 trillion per year (~$50bn) of additional resources is anyone’s guess because this is one government which revels in keeping its plans a total secret. One can only say two things with certainty -one, Modi will be extremely keen to cement his legacy with a couple of flagship projects/programs which has a transformational impact on society. Two, the consummate politician that he is, he will have his eyes firmly on what programs will drive the optimal political benefit for the 2029 elections (and all the state elections over the next few years).

The list of potential programs is endless. Below, I discuss briefly a few ones which I see as critical ones. I classify them into 3 categories: A) long term strategic B) medium term economic growth and C) quality of life. Obviously, most of these programs will tick all three boxes, the classification is based on how a politician like Modi would want to see it. Admittedly, some of the resources might also simply get used up in standard fiscal management as well – ie Modi might simply want to reduce fiscal deficit at a faster pace, or execute the long pending reduction on tax surcharges on the rich or fill up the job vacancies in the government.

The second part is investment in energy transition. So far, the Modi government has bet big on solar but now it has also stated its intention of expanding its nuclear fleet (add 15 GW by 2030). While investments in solar power has been largely driven by private players, the government will need to play a big role in setting up nuclear plants. A back-of-envelope estimate for the cost of the plants would be $50 billion and it would be reasonable to assume that the government will have to invest close to half of that amount.

The fiscal math

Assumptions

Fiscal deficit falls to 4.5% by 2025-26 and below 3% by 2028-29.

A few points:

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

The 1946 vote and the Muslim mandate for partition

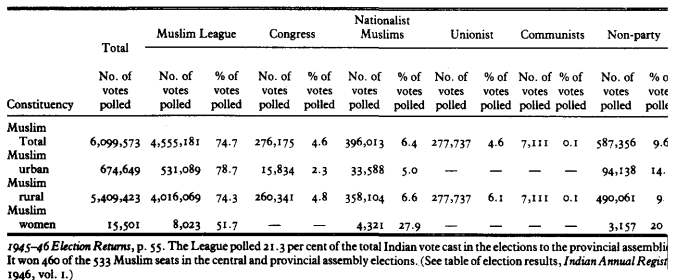

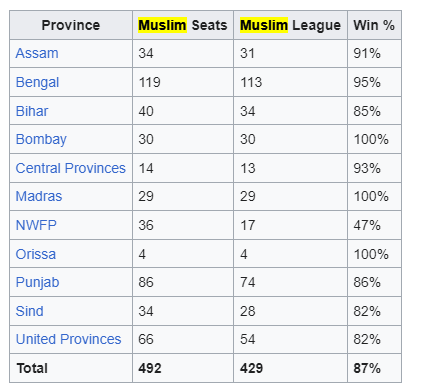

The 1946 elections remains inarguably the most consequential election within the Indian Subcontinent. Jinnah’s Muslim League (ML)went into the polls with a single-point agenda of partition and the Muslim voters responded with feverish enthusiasm, delivering a crushing victory for ML across all provinces, thereby paving the way for partition. The party won an overwhelming 75% of the Muslim votes and 87% of the Muslim seats, and except for NWFP, its minimum seat share was 82% (see table below). Of note, provinces from current day India -places like Bombay and Madras, which had zero chance of being part of a future Pakistan – gave a 100% mandate to Jinnah.

(for those who are not aware, we had a communal electorate at that time which meant Muslim voters would vote exclusively for Muslim seats)

Facts belie claims of Muslim society non-representation in mandate

As regarding the role (culpability?) of the Indian Muslim society in facilitating partition, establishment historians put forth two arguments. One, Jinnah had kept the Pakistan promise deliberately vague and hence the voters did not realise what they were voting for. Two, the overwhelming mandate from the voters cannot be taken as representative of the sentiments the whole society as only a tiny proportion of Muslims had the right to vote. The first one is a qualitative debate and can be debated endlessly. But the second assertion is easier to examine since we have actual voting and demographic data and that is what I will endeavour to do in this post. I reference one specific claim which is quite popular in social media — that the mandate was only from 14% Muslim adult population, based on an article written by a leading X handle, Rupa Subramanya, who has a rather interesting history with respect to her ideological leanings.

The analysis that follow will show that at least one adult member (mostly male) from close to 40% of the Muslim households in British Indian provinces and at least 25% of Muslim adults were eligible to vote .

I cannot emphasize enough that this is not something which should be used to question Indian Muslims of today. The founding fathers of the modern Indian nation made a solemn promise to Muslims that they will be equal citizens of this nation and that should be unconditionally honoured. But as a society, we should have the courage and honesty to acknowledge historical facts rather than seek to build communal peace on a foundation of lies, as the left historians have done; Noble intentions are not an excuse. Talking of fake history, one cannot but marvel at the sheer degree of control over the narrative of the establishment historians that they have managed to perpetrate the claim about the 1946 vote for more than seven decades when there is hard quantitative data available on number of voters, the country’s adult population etc. One can only imagine the kind of distortions they would have done to medieval history where obfuscation would have been infinitely easier.

Some basic facts about the 1946 elections

I will start off with some facts and estimates which are broadly indisputable.

A) The 1946 provincial elections was limited only to British Indian provinces

The 1946 elections was limited to provinces directly ruled by the British which accounted for roughly 3/4 of British India’s population. While the provincial representatives in turn elected 296 members of the Constituent Assembly, the princely states nominated 93 members the constituent assembly, i.e in proportion to their respective population. With ML bagging 73 of the 78 Muslim seats in CA, the partition debate was as good as sealed.

B) 28% of the adult population of the provinces was eligible to vote

The total strength of the electorate was 41.1 million voters while the total population of Indian provinces was 299 million. Taking into account only the adult population (age of 20+, ~50% of the population), it implied 28% of the population were eligible to vote.

(data is sourced from Kuwajima, Sho, Muslims, Nationalism and the Partition: 1946 Provincial Elections in India, Manohar, New Delhi, 1998, p. 47.)

C) An estimated 25% of the adult Muslim population of the provinces were eligible to vote

While I am unable to source the actual data for the percent of eligible voters within Muslim community, there is no reason to think it would be an order of magnitude lower than the overall 28% number. As I show in the Appendix, voter and turnout data indicates the number should be in the 25% range, if not higher; i.e. about 9 million Muslims out of 37 million adult Muslim population in the provinces were enfranchised.

D) Close to 40% of Muslim households had members eligible to vote

The 28%/25% voter ratio discussed above is skewed by the fact that very few women were allowed to vote. Only 9% of adult females had voting rights which in turn implied that 46% of adult males had voting rights. (Source: Kuwajima, Sho). If we assume the same proportion for Muslim females, that would imply little over 40% of Muslim adult males were enfranchised.

E) 75% of the 6 million Muslim votes went to ML

4.5 million Muslims voted for Muslim League out of a total 6 million Muslim votes cast from an electorate size of 9.2 million. Of note, there is no major urban-rural divide — the figure for rural areas is 74% vs 79% for urban areas.

Muslim mandate way more broadbased than projected in mainstream narrative

Based on the above data, at the very least, one has to concede that 25% of the Muslim society had a say on the issue of Pakistan and three-quarters of that group did vote for creation of an independent Muslim State. This severely undercuts the claim that only a tiny elite voted for Pakistan — Rupa’s 14% figure, for example, is clearly wrong **. But even the argument that the bottom 75% had no say on the issue is inaccurate because the voting rights were not just based on class, but also on gender. As noted above, close to 40% of adult male Muslims were enfranchised — in other words, 40% of Muslim households had an adult member who could vote. And of this 40%, three-fourths or 30% chose to vote for Pakistan. That clearly means that a much larger cross-section of the Muslim society had a say than just a tiny elite or the educated middle classes (or the salariat class as Ayesha Jalal calls it). This appears to be a more reasonable interpretation of a mandate given the context of the time when universal for women was still a new or evolving concept in many advanced democracies.

** The error that Rupa makes in arriving at the 14% figure is two-fold. One, she takes the adult Muslim population for entire British India (~44 million) whereas the elections were held only for provinces (~37 million). Second, she uses actual voter turnout (6 million) instead of the total size of the Muslim electorate (~9.2 million).

What are some of the counterarguments to the above interpretation?

A) What about the fact that the Muslims in princely states had no vote?

This argument, on the face of it, is not without merit. But one needs to be honest about framing it — this is not a case of a vertical class divide in enfranchisement but a horizontal regional divide. Therefore, the proponents of the non-representative nature of the mandate will have to make the case that the Muslim subjects of the princely states would have taken a significantly different view on Pakistan versus the ones in the provinces, just harping on the class divide will just not cut it.

Let us look at what the data can tell us. The adult Muslim population from the princely states would be another 8 million. Based on 1941 census data nearly 60% would be from three large states — Hyderabad (17%), Punjab (18%) and Kashmir (24%). Is there any reason to believe that the Muslims of Hyderabad or Punjab would have voted very differently versus their neighbor provinces of Madras Presidency or Punjab province? A debate on this issue is beyond the scope of this post but I would say that the burden is on those making the “non-representative mandate” argument to make that case.

For the record, if we take total Muslim population figure, then the proportion of adult and male adult enfranchisement of Muslim community would go down to 21% and 34% respectively

B) Muslim women were largely excluded

As noted earlier only about 9% of adult women were enfranchised. Assuming a similar (or lower) figure for Muslim women, indeed they had little say on the matter. One interesting aspect is that even among the Muslim women eligible to vote, very few seem to have turned up to vote. Only 15K of them voted which would be a turnout in the low single digits at best! But among those who did vote, more than 50% voted for ML, which is admittedly well below the overall support of 75%. But still, the fact is that a slim majority of Muslim women too voted for Pakistan. Also, electoral mandates need to be interpreted based on the context of that time and broadbased women suffrage was still at a relatively early stage even in more advanced democracies.

C) Hey! only 4.5 million out 37 million Muslim adults voted for ML

This would mean only 12% of adult Muslims expressed support for Pakistan. In a very narrow mathematical sense, this is, of course. right. But this is just not how electoral mandates are interpreted in any democracy. If one uses this yardstick, it would mean Presidents in one of the world’s oldest democracies, have been consistently elected with support of just a quarter of the electorate because voter turnout in US has generally been around 50%. The ones who had the right to vote but chose not to exercise it will need to be excluded from any interpretation of the mandate.

Conclusion — acknowledge history and move on

Partition has a cast a long shadow on Hindu-Muslim relationship and perhaps it was a wise decision in the immediate aftermath to underplay the Indian Muslim community’s role in it. But a fiction cannot be the basis for a permanent peace. At some point, we will all have to collectively acknowledge the historical facts and have the maturity to move on. One additional problem also is that this fictional narrative about the mandate further feeds into the Muslim victimhood that they had chosen a secular India over a Islamic Pakistan and have been betrayed by rising Hindu majoritarianism. A honest appraisal of history might perhaps lead to a more constructive political strategy.

Appendix — estimate of eligible voter percent within Muslim community

A) The Muslim population in the provinces was 79.4 million. Given higher birth rate among Muslims, the adult population is lower than the national average — using Pakistan’s 1951 census data as a proxy, I estimate the adult Muslim population to be 47% or 37 million.

B) Total number of Muslim votes cast was 6 million (Ayesha Jalal)

C) Average turnout across communities was around 65%

D) If one assumes a similar turnout for Muslims, then the total electoral size for Muslims comes to 9.2 million which implies 25% of adult Muslim population was eligible to vote. It is quite likely that the turnout was much lower because the turnout amongst Muslim women was abysmally low (Ayesha Jalal)

So it is reasonable to conclude that at least 25% of the adult Muslim population living in the provinces were enfranchised in 1946.

The late “Cho” Ramaswamy was a Indian actor, comedian, editor, political satirist, playwright, film director , Member of Parliament and lawyer . in 1970 he had an argument with his friends who dared him to start a magazine and to win the bet , he launched a political magazine that turned 54 this year. The first issue had this iconic cartoon where one donkey says to the other ” Looks like this Cho fellow has launched a magazine” and the other replies “Great , we will have a feast then!”. The cartoon donkeys make their appearance once in a few years while all of us readers have been reading Thuglaq for decades !

I happened to attend the 54th annual meet of Thuglaq, the one-of-a-kind event where the entire rank and file of the magazine meet with its readers, on Pongal day ,as it always happens. This unique practice was started by Cho and after his death in 2016, S. Gurumurthy, the Chartered Accountant, Journalist and RSS Idealogue has been successfully running the magazine while maintaining such traditions as well. Cho, while his sympathies for the right wing and Modi was always transparent , also was known for changing his views as the situation on the ground demanded and did not hesitate to critique even sharply the parties he supported. He was famously responsible for the TMC (Tamil Manila Congress – Moopanar and P.C Chidambaram led) formation and TMC – DMK alliance and helped in shaping the BJP-DMK Alliance during Vajpayee’s time as well when he went against his childhood friend Jayalalitha. Under Gurumurthy, while Thuglaq retains most of the founding tenets of the magazine, discussing mostly only politics and a sliver of spirituality, the irrepressible and at times irreverent humor of Cho is definitely missing. Gurumurthy seems to have almost made it a dry right leaning political magazine to the mild disappointment of long-time readers like me.

In spite of the strong shift to the right, Gurumurthy has retained and even strengthened some unique features of Thuglaq. One being inviting political leaders of all hues including the ones he opposes like DMK, Congress, Communists to share their experiences and points of view in the magazine. And to continue and strengthen this annual unique event on Pongal day when the Editor of the magazine and his entire staff meet and interact with all the readers and invite political leaders to address and interact with the audience as well. Who’s who of Indian politics have attended these meetings – Advani, Modi and most of the BJP Leaders, the erstwhile Janata leaders like VP Singh, senior communist leaders and Tamil Nadu leaders across political parties.

For this year’s event, the two main guests were Shashi Tharoor from Congress and K Annamalai, the firebrand BJP Tamil Nadu Chief. Sadly, since Annamalai was coming in from a meeting at Delhi, his flight was delayed and by the time he entered the Music Academy Hall, Shashi had finished his speech and had left. The program began the way it always does, with the editor introducing the entire staff of the magazine on stage starting from the veteran reporters like Ramesh whom most of Tamil Nadu knows to the attenders. This is again a unique gesture that surely must be appreciated. Then selected readers from the audience come to the stage and make their comments, queries and criticisms to which Gurumurthy replies. This year, apart from the regular questions about state and national politics , there were a few questions and concerns regarding the Maldives standoff and Guru gave his opinion and also deferred to the veteran diplomat and politician and ex Minister that Shashi is and requested him to give his point of view when his turn came. The audience as expected was mostly sympathetic to BJP’s cause.

Shashi spoke well, noting down all the key concerns and objections raised by the audience against Congress and addressed them valiantly. He also accused Modi government of subsidizing North at the cost of the South, lamented the subjugation of federalism and also explained the Maldives situation in an objective way without blaming the BJP government but cautioning it to be careful not to push Maldives into the axis of China. Ram temple issue being a topical one, he took it head on saying that he will visit the temple but not on the 22nd as he has in any case not been invited and would not want to go even if he were as he felt it was made into a political event. This caused some unrest in the audience as it did when he was overly critical of Modi. Overall, it was a measured speech, fully knowing it was a partisan audience who were against his world view, Shashi Tharoor, I felt stood his ground gracefully. It was comforting to see Gurumurthy come up to the stage after and admonishing the audience for interrupting Tharoor’s speech, commenting that since Dr Shashi Tharoor maintained the decorum of the forum, it behooves the audience too to do the same even if they believe he is all wrong.

Then came the star of the show, Annamalai who has caught the imagination of the public in the state especially those who desire an alternative to the Dravidian parties. His was a systematic take down of the DMK, its history and all that he felt was wrongs done by them. He also attempted to answer all the criticisms laid by Dr Tharoor, replying to the preferential treatment to the North charge, gave a population-based defense of the budget allocations favoring the North. He explained the BJP’s plans for the south and Tamil Nadu in particular. Gurumurthy too jumped on to the same North – South subject later and gave a historical perspective based on argument that the north suffered more from the partition which at least I could not buy fully.

A few broad inferences for me from the event

For Congress, it appears as though this boycotting of hostile TV Channels and media is a petulant and self-defeating act. I too cannot stand some of these loud TV Channels and can understand the reasoning but if one is running a political party, surely one needs a thicker skin and like Shashi Tharoor showed, one can hold their point of view even among a partisan hostile crowd and come out with head held high! I overheard a lot of the audience commenting that “Tharoor is a good leader but will he survive in the Congress”. It is up to the Congress to convince people of that and give such leaders more responsibilities and have them engage with people more.

For BJP, this preferential treatment of North over South and the damage to the federal structure narrative is hitting home to the audiences in this part of the world and even to those who are favorably disposed towards it. The narratives countering it, the ones I heard from Annamalai and Gurumurthy were not entirely convincing. There have been other arguments on this subject which have featured in BP Podcasts by folks like Maneesh about Freight Equalization policies and such which seems to have some merit in them but are seldom heard here. Are those too nuanced and complex arguments, am not sure but the ones that I listened to now still leave me with the feeling that we in the south have been hard done by both the Congress and more so by the BJP Government.

Interacting with the audience live, especially if it is a large one and answering them impromptu seems to be a rare occurrence and should be celebrated more. The audience too needs to learn to respect the speaker and not jeer if an opposing point is presented. The audience in this event have been that historically and when they went a bit haywire, they were immediately pulled up. Politicians, those who are well qualified (Please note I do not say educated!) and passionate about a subject can still convey their stances without resorting to name calling and hyperbole. Both Shashi Tharoor and Annamalai were strong but objective and respectful in their speeches.

The argumentative Indian can also be objective and respectful and can engage in constructive dialogue and achieve much more!

The YouTube Recording of the entire event.

This post is contributed by याज्ञवल्क्य, also known as @Saiarav Sai (@Saiarav) / X (twitter.com) from X.

The God lording over the oil market has almost always turned a benign eye towards Modi. Oil prices fell by nearly half within a year of him becoming the PM and has stayed moderate for most part of his rule, a big blessing for a a country which depends on imports for more than four-fifth of its consumption. And Modi has used this divine largesse really well, taxing it heavily and testing the limits of his political capital and used these revenues to fund his ambitious capex program amidst anemic overall tax collections. How the timing of oil price movements has been near perfect politically for him can be a separate post in itself; but I will just note that if you had asked an oil analyst in March 2022 where oil prices would be at the start of 2024 if A) the Russia-Ukraine war continued to drag on and B) the developed world saw a period of double digit inflation — his/her answer would likely have been a triple digit figure. But yet here we are, at the start of 2024, with Brent trading under $80.

Petrol and diesel prices stay high despite lower oil prices

So here we are, with oil under $80 and yet the Modi sarkar has not deemed it fit pass on the munificence to the hapless consumers who still have to cough up nearly Rs.100/litre for petrol and diesel, the same level it was in early 2022 when oil had crossed $100/bbl. You might be wondering why I have started with a rambling introduction to get to this point — and I have no reason to offer, except perhaps that I am abusing the munificence offered by Medium, liberated from the character limit from my standard social media app. Thanks for indulging me, dear reader, now I will get down to business, I promise. (Not a good thing to abuse munificence of any kind, which is kinda the point of this post).

A lot of noise, too little light in the debate on fuel pricing

While this issue periodically generates heated debates on X, for the most part, it has been largely ignorant chatter and largely driven by one’s political leanings. And I have not come across any piece in mainstream media which has attempted to shed light on this issue. And that is both astonishing and extremely sad — here is the question regarding pricing of the most important commodity for any economy, and people do not know how it is priced? And we are talking of third largest oil consuming economy in the world here. It is astonishing because oil and its products constitute one of the most transparent, liquid and well understood markets amongst all commodity markets.

So here is my modest attempt to shed a tiny bit of light.

In India, the oil marketing business is largely dominated by oil PSUs who also have a refining business. The business model for oil refining and marketing is pretty straightforward:

A) OMC purchases oil, most of it is imported. The price of oil is linked to Brent, the global oil benchmark. So the refiner pays Brent oil price + ocean freight + insurance. (I am keeping it simple here — the actual price can be a bit higher or lower than Brent)

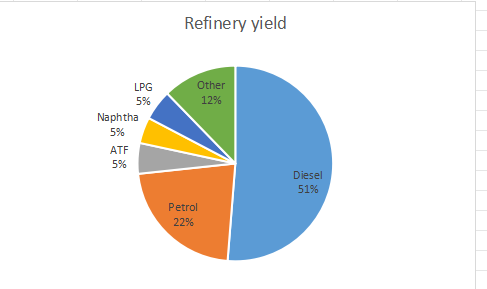

B) The OMC refines the crude oil in its refineries resulting in various petroleum products — primarily three high value products diesel, petrol and ATF but also propane, naptha etc. The chart below shows the yield of BPCL refineries in 2022–23 — the three high value products account fot nearly 80% of the total output.

C) The products are sold to end customers. For petrol and diesel, which is what this discussion is about, this would mean transporting the products to petrol pumps. Further, the marketed volumes for an OMC could be higher than its refining capacity, which means it will have to buy some part of its products from private refiners (Reliance and Nayara).

The OMCs provide value-add at two stages — refining the oil and marketing the oil and expect to be rewarded for the same. Let us take an example of how that works. First, at the refining stage, the company makes a margin which is the difference between weighted average selling price of all the refined products less the crude landed cost — this is called Gross Refining Margin or GRM. High value products (petrol, diesel and ATF) sell at a price well above the crude oil price while a product like Naphtha sells for less than the crude price. But keep in mind, the high value products account for 80% of volume and hence driven the GRM. As the term implies, this is just the ‘gross’ margin and the company obviously has operational expenses during the refining process.

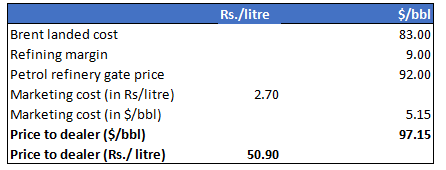

At the marketing stage, the company would expect a margin for maintaining a retail network and transporting the products to the dealers. And of course, there are costs of marketing the products as well. As of 2019, the per litre marketing cost + margin was Rs. 2.0–2.5 per litre (source: page 60 of this Petroleum ministry report). So let us say, its Rs. 2.7 currently accounting for inflation. The unit of measurement will keep shifting from barrels to litres, so you might want to keep in mind that 1 barrel = 159 litres.

Continuing from the above table, let us say, the OMC sells petrol at the refinery gate at a price of $92 (which would be refining margin of $9/bbl). Adding in a marketing cost of $5, the price to the dealer would ultimately come to Rs. 50.9/litre.

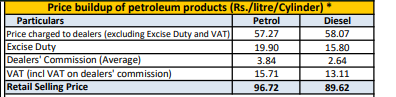

Adding to the price paid by the dealer, we then have the central and state government taxes and the dealer margin. Currently the price build-up for petrol and diesel (for Delhi) stands as follows:

Source: PPAC November 2023 report

Note that the price at which it is sold to the dealer is Rs.57–58 which implies a per barrel price of $109–110 while Brent currently trades at <$80. Since the marketing cost & margin is fixed, that means, the OMCs are getting a refining margin of $20+/bbl on both petrol and diesel.

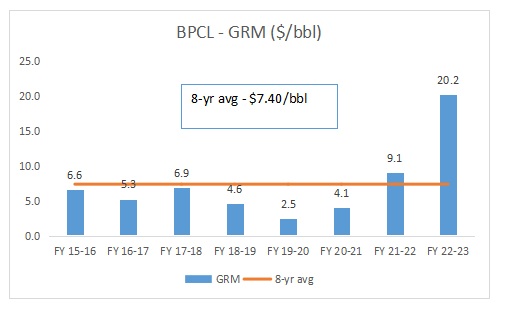

Is $20 high, or is it low, or is it normal? Below is the chart of BCPL’s GRM for the last 8 years. Note that this is the GRM for its entire set of product and petrol and diesel margins will be a couple of $ higher.

Typically, OMC GRMs have averaged mid single digits and the last two years, and especially FY 22–23 were outliers.

But what is the official pricing policy?

In theory, petrol and diesel prices are deregulated which means prices track the global prices for the two products (which is simply Brent price + regional refining margins). But it does not take an oil market expert to figure out that the policy has been quietly buried since early 2022.

The pricing is arrived at by what is called the Trade Parity Price (TPP) which is the weighted average of Import Parity Price (IPP) and Export parity Price (EPP) weighted in the 80:20 ratio. IPP simply means what is the theoretical price at which petrol or diesel can be imported to India ( we do not need to import since we have surplus refining capacity) — that price is basically the one at which refiners in our region will find it attractive to export to us. In other words, IPP for petrol and diesel is based on the refining margin of the two products in our region. The same concept applies for EPP — it is the price at which one can export which is linked to refining margins in the key export markets. Typically, the margins in Singapore market is used as the benchmark. And that explains why refining margins shot up in the last couple of years.

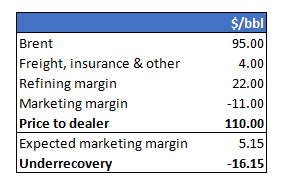

Underrecovery ….or how OMCs made bountiful GRMs but little money in FY 22–23

A $20/bbl GRM in FY 22–23 should have been a major cause of celebration for OMCs but it was not for the simple reason that the GRM was a notional number. For all of FY 22–23, the OMCs were selling petrol and diesel at Rs.57–58/litre to the dealers which is roughly around $110/bbl. Now considering Brent averaged $95 during the year and shipping costs had shot up during the year, this is how BPCL’s overall margins would have looked for petrol assuming a $22/bbl margin. Remember that the company is supposed to make $5.15/bbl towards marketing margin and costs. Instead, they incurred a loss of $11/bbl. And that is what OMCs, quite morosely, term as underrecovery. In reality though, the company did make a combined refining & marketing margin of $11/bbl but if one assumes refining and marketing costs of, say $8–9/bbl, they made very little in terms of cash profits from sale of petrol. There is also the further angle that they would have had to purchase some portion of petrol and diesel from Reliance and Nayara at global prices (ie $95+$4+$22 = $122) and sell that for $110. And on top of that, they had to incur huge losses on LPG cylinder sales, so yea overall a tough year, but I digress. The case that BPCL will be putting forth to the government is that they made $16/bbl underrecovery on petrol and diesel in FY 22–23 and they should be allowed to recoup those “losses” — my rough estimate is that that amounts to Rs.25,000 crores to be recouped!! To put this number in perspective, BPCL annual profits have averaged 8–12K crores in the past and the company is asking that they be allowed to make 25–30K crores for FY 22–23 because, hey, GRMs were so high.

So what is a reasonable GRM for OMCs?

Singapore refining margins for petrol and diesel are currently around $10 and $20 respectively. So if one goes by that figure, diesel should be around Rs.55 to the dealer might well be justified while petrol price should be around Rs.51. As a reminder, the current price to the dealer is Rs.57–58.

So even based on market pricing, there would be a case for cutting the petrol price. Of course, the question that arises is what about the losses incurred in FY 22–23, which I will come to later. But I would argue that the government has anyway jettisoned their pricing policy and should therefore stick to that changed stance and just view it as what is a reasonable GRM that the OMCs should be getting. I would say, $6.5/bbl is a pretty healthy margin. Or stick to the current pricing policy and slap a windfall tax (just like they do on exports of refined products).

One counterargument to this is that OMCs have ambitious growth plans and these high GRMs will be really helpful. In my view, they should just be asked to borrow money.

In the next section, I discuss what the potential for cutting prices is.

If we go strictly by the official fuel pricing policy, then BPCL needs to be allowed to recoup its underrecoveries of Rs.25K crores, so any cut is out of question, for this year, or the next, or maybe even the one that follows — and that is asuming oil does stay at $80. Or Modi could request BPCL to be let bygones be bygones — and I am sure the BPCL CEO, as a good corporate citizen, will give it a sympathetic hearing — and ask them to adjust the price down to current TPP levels, in which case, as I have pointed out earlier, there is scope to cut petrol prices by >Rs.5/l and diesel by a couple of Rupees. Votaries of free market can stop reading at this point because as I had suggested in the previous part, the government should just tell the OMCs that they stay happy with a GRM of $6.5/bbl. That would be $8.5/bbl refining margin for both petrol and diesel.

If we go with $8.5/bbl, then what would be the price to the dealer? I am assuming Brent price of $80/bbl though prices have generally remained a few dollars below that level over the last few weeks. Also note that since a large component of our imports are now discounted Russian crude, the average import price should be below Brent ( we also buy cheaper quality, lower price crude vs Brent generally, but not getting into further details). At $80/bbl and $8.50/bbl of refining margin, we can potentially reduce prices by Rs.6–7/litre. But there are two factors which need to be considered as well, one positive and one negative — the OMCs are sitting on huge surplus profits built up over the first nine months of FY 23–24. On the other hand, the OMCs are currently selling LPG cylinders at a loss.

How much surplus profits have OMCs build up?

Let us look at BPCL’s financial performance since the start of FY 22–23. Excluding exceptional items, the company’s profits during FY 22–23 would be around Rs. 5–6K crores. This compares to historical annual profits of Rs.10–12K crores. So that would mean a loss vs historical average to be recouped of, say Rs. 5K crores (not the insane underrecovery figure of Rs.25K crores or ~Rs.20K crores post taxes). How much after-tax profit did BPCL make in 1H 23–24? Rs.19K crores!! Yes, you read that right — they made 1.5x in 6 months vs their peak annual profit historically. If we consider Rs. 13K crores as reasonable profits for FY 23–24, they have already achieved it *AFTER* recouping their losses for FY 22–23. In other words, even if they do not make another Rupee for the rest of the year, they would be fine. But given benign oil prices in Q3 , they should be making outsized profits in Q3 as well. Short point: the company is sitting pretty as far as profits go.

While I have not analyzed the other two OMCs in similar detail, the profit performance broadly follows the same trend as BPCL, as is to be expected.

Losses on LPG sales, possible combinations for price cuts

At current global LPG prices, OMCs are making a loss of between Rs.150–175 per cylinder sold. The OMCs have made humongous surplus profits from LPG sales in 1H 2023–24 — as per this article by Devangshu Dutta, those profits are not recorded in the books, the surplus profits are instead placed in an adjustment account to offset future losses. Mr. Dutta estimates the fund has accumulated Rs.12K crores by end-September. I will leave out this part in my analysis since there is no disclosure by OMCs in this regard but if true, it provides further upside to potential price cuts.

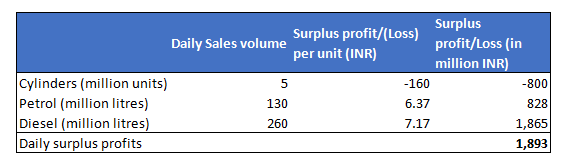

At $80 oil price, this is how I see surplus daily profits earned by the OMCs in aggregate. They collectively make Rs. 1.89 billion of surplus profits every day.

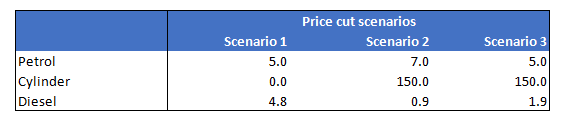

So a price cut can follow any of the following combinations. Politically, a sharper cut in petrol and LPG prices is more preferable ahead of the elections (scenario 2 and 3) while a cut in diesel prices would be better for battling inflationary pressures. And there is upside to these price cuts if one considers that the OMCs are sitting on large surplus profits this year so far. My own preference would be somewhere between scenario 1 & 2 but I would definitely not grudge Modi dipping into the OMC’s surplus proifts and going for a bigger cut. Of course the risk in that case is he will need to revert to more normalised prices by the end of this year. Or horror of horrors, bring down the fuel taxes.

I would like to highlight that I consider these cuts as the floor estimates considering assumptions for the price build-up are quite conservative, whether it be on crude oil landed cost or marketing costs and margins. Apart from the fact that OMCs are already sitting on huge surplus profits.

Postscript: I have grown tired of explaining why these price cuts have no impact on the fisc. As you can see from the analysis above, price cuts do not require even a single Rupee of tax cuts by the centre. Currently, all the surplus profits are just flowing into OMC’s Profit & Loss account.

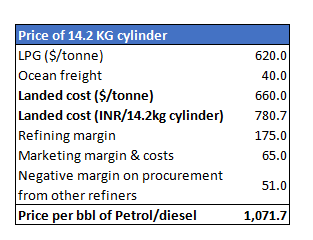

Appendix — LPG cylinder price math

Source: based on this 2017 PPAC report — domestic costs in 2017 was Rs.120. Should possibly be currently in the range of Rs.150–175 after accounting for inflation

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

Continue reading Yogi has not been an economic miracle man for UP…so far