My personal belief is that jati-varna was one of the major reasons that India did not Islamicize more than it did. These sub-elite solidities “absorbed” external shocks and mediated individual relationships with the world. Collective entities like this are common across the world, but the genetic distinctiveness of these groups is like nothing you see elsewhere (with the possible exception of endogamous isolation like premodern Ashkenazim). I also believe that the jati in particular predates the arrival of the Aryans 3,500 years ago. Varna-like concepts exist in other Indo-European societies, but only jati exists in India, and I believe that genetics will uncover jati-like stratification in the IVC over time. Jati may be one reason that the IVC seems archaeologically to be an “anarchistic” society in terms of governance and politics insofar as they can infer anything from material remains (there seem to be no grand public buildings as in Mesopatamia or Egypt).

But, today, in 2022, the jati-varna system is a problem for India. In particular, I think the reservation system is socially toxic and economically inefficient. Because I have libertarian conservative viewpoints, I have always opposed caste-based reservations, just as I oppose affirmative action in the USA. This has little to do with empirical or utilitarian calculus and everything to do with deontological principles. But, from a utilitarian perspective, I believe that reservations result in the misallocation of talent, as well as emigration.

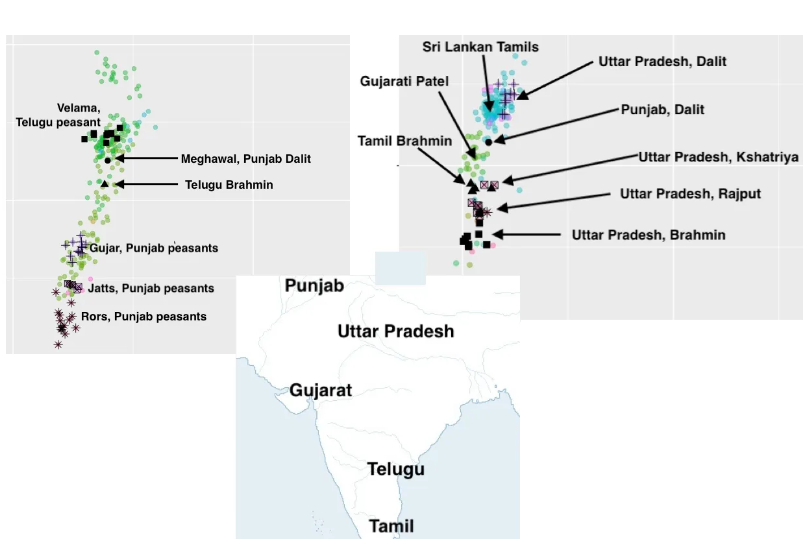

How to fix this problem? The genetics indicates endogamy rates of 99% or less for possibly a thousand years or more. Today, the jati-varna endogamy rate is lower. Perhaps 95% is the high bound from the estimates I’ve seen. This means within several centuries jati-varna as we understand it will not be viable. The rate of genetic/social/cultural exchange will be too high to maintain traditional solidities. This will not mean that all castes will disappear; some will likely persist, but many societies have endogamous minorities. The way India is unique is that it is a whole civilization that is built around endogamous minorities. This does not scale as well to a modern economy and unitary society, and it is cannot persist if current social trends continue.

This problem will “naturally” take care of itself in both India and Pakistan (two countries where endogamous communities are ubiquitous), but, there are possible social and cultural movements that can accelerate or retard this process. The transformation of Hinduism into a more cohesive and confessional religion will probably be part of this. Like jati-varna, Hinduism’s strength was its fractious decentralization, as it absorbed and flexed in various directions to maintain its integrity in the face of proselytization. But in the world of 2022, the strategies of survival and persistence in the face of five hundred years of Muslim domination (in North India) are not appropriate; cultural involution and retreat simply invite defeat. The extremely diverse and almost contradictory nature of Hinduism allowed it to be a catchall system that integrated many jati groups with idiosyncratic beliefs and customs. The two reinforced each other as parallel institutions. Arguably, the weakness of jati will be the weakness of Hinduism unless the latter evolves and changes. One primary reason that non-Hindus never convert to the religion is that conversion still puts one outside of the jati-varna social networks of other Hindus while ostracizing oneself from one’s birth community.

Of course, some Hindus like the system the way it is. Some of these go by the term “trads,” but these types simply say out loud what the revealed preference shows is the majority viewpoint of most Hindus in India. What do they worry about? Higher-status groups do not want to become lower-status. Also, some high-caste Hindus believe they are more beautiful (lighter-skinned) and intelligent than lower-caste Hindus, and they do not want to dilute their human capital advantage. Objectively, it seems clear that many high-caste Hindus are indeed lighter-skinned and have facial features considered more beautiful than that of other Indian castes (I’m talking about Indian preferences on the whole). Additionally, whatever you may think about the heritability of intelligence, this is also certainly a possibility for differences between the groups.

But there doesn’t need to be such a great concern. Most societies have intelligent and beautiful subgroups, but they are not restricted to a particular social or political element. Restricting these traits to a particular social and political group causes problems, as you can see in India. The reality is there are beautiful/handsome and intelligent Dalits, so why not marry them if you are a Brahmin? These characteristics will persist, and the upside is that the social divisions between the jatis will diminish, and India can have a cultural matrix that’s more amenable to economic growth and individual liberty.

As someone with a conservative bent, there are natural hierarchies and status differences in any society. This is normal, and total leveling will never be possible, nor should we even aspire to it. Difference is worth appreciating. But the system of jati-varna in India as it is operationalized today is not conducive to human flourishing because it retards the development of broader social and cultural institutions that allow for national collective action. This is not abstract. China is a perfect example of a society with class status, but never has it had jati-like endogamy. Radically different dialect groups, like Hakka and Cantonese, freely intermarry with minimal conflict or controversy, so long as socioeconomic status is this. This is the future. You can delay it or ride the tiger.

In the run up to Indian parliamentary elections in 2024, there is excitement in some sections of social media about “freemarket” ideas espoused by C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) and the Swantantra Party he helped found in 1959.