Brownpundits have come on Youtube.

Currently, i have only uploaded History series podcasts on Youtube, but hopefully in the coming days we can upload some vodcasts and some popular podcasts on too

Brownpundits have come on Youtube.

Currently, i have only uploaded History series podcasts on Youtube, but hopefully in the coming days we can upload some vodcasts and some popular podcasts on too

https://brownpundits.libsyn.com/teaching-in-the-time-of-covid-19

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/teaching-in-the-time-of-covid-19/id1439007022?i=1000512866865

https://www.stitcher.com/show/brown-pundits-podcast/episode/teaching-in-the-time-of-covid-19-82364378

COVID-19 is wreaking havoc on the lives of young children, students, and youth. The disruption of societies and economies caused by the pandemic is aggravating the pre-existing global education crisis and is impacting education in unprecedented ways.

Brown Pundits- Shahada, a UK College Lecturer, discusses COVID-19 with Michelle Kerr, a Maths Teacher from California. They compare their experiences, concerns and impact.

Covid-19 has impacted on Education on so many levels and there are many parallels with society in general:

COVID-19 is having a negative impact on young people’s mental health. We are concerned that, with most young people not currently attending school and many young people not having access to resources and materials with which to learn, there will be a subsequent detrimental effect on both academic attainment and wellbeing. Exams have been cancelled in many states and here in the UK. This is having a negative impact on attendance and motivation.

The COVID-19 crisis is likely to have a long-lasting impact on young people’s mental health and the services that support them, including schools and children’s services. The Government must consider this throughout its emergency response and policies to recover from the crisis. Has COVID-19 highlighted pre-existing decline in mental health?

The impact, particularly on groups who are already disadvantaged, is likely to widen existing inequalities and to contribute to a rise in young people looking for mental health support. Is this a reflection and consequence of inequality in education?

Discussions touched upon the existence of hierarchy in education and its parallels in greater society? For instance, will deprived students disproportionately be disadvantaged? Ultimately is this a reflection of class privilege?

A controversial point discussed was weather Teachers have a professional responsibility to physically go into the classroom. Both expressed very different perspectives!

Its been argued that Standardised tests are not an accurate representation of a student’s abilities and they lack reliability. We touched upon the controversial issue of removing standardised testing in education. Weather standardised testing should be formally put to an end. Has the removal of standardised testing been accelerated as a consequence of COVID-19? Will this result in a lowering of standards and skills? And again which group will be disadvantaged and advantaged?

Time will tell, the true long term impact of COVID-19 on Education…….

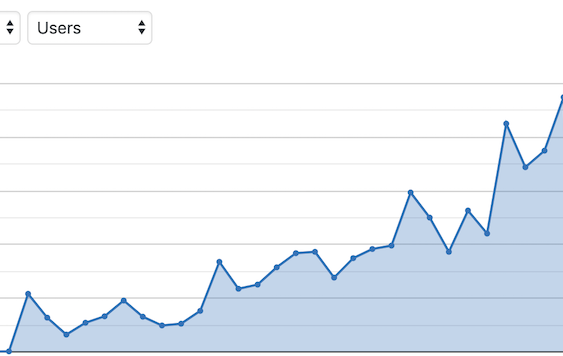

Since the readership is now plural majority Indian (going by IPs) I should probably ask this question… (JR’s OIT posts are now shared routinely hundreds, even thousands, of times on Facebook)

“A good story is a problem. It makes your mind shut down, and you ignore everything else”.

ATF agent in Manhunt: Deadly Games

I have recently been reading ‘Billion Dollar Loser’ by Reeves Wiedem, about WeWork and its founder Adam Neumann. It reminded me of an NYT article from Amanda Hess last year titled “Fyre Festival, Theranos and our never-ending ‘scam season'” about the rise of grifting among Millenials. She pointed to Billy McFarland (Fyre Festival), Elizabeth Holmes (Theranos), and Anna Delvey (SoHo grifter) as examples of American Millenials who have become infamous in the last few years for overselling bad products/personalities and underperforming or outright lying people out of enormous amounts of money. Jia Tolentino wrote in 2018 that “At some point between the Great Recession, which began in 2008, and the terrible election of 2016, scamming seems to have become the dominant logic of American life.” She further expounded on this phenomenon as “Grifter season comes irregularly, but it often comes in America, which is built around mythologies of profit and reinvention and spectacular ascent. The shady, audacious figures at its center exist on a spectrum, from folk hero to disgrace. The season begins when the public catches on to a series of scammers of a particularly appealing sort—the kind who provoke both Schadenfreude and admiration.”

Adam Neumann, the co-founder of WeWork, is another addition to this list. Some on Twitter would argue that Elon Musk, and to a certain extent, Travis Kalanick, should be mentioned in the same breath as these grifters, but he is not a millennial and at least has something to show for all the hype. There are many similarities among this lot, including the worship of Steve Jobs (Neumann in passing, Holmes to the extreme), megalomania (Neumann telling a rabbi, “I am WeWork”), abusive behavior with employees (Neumann hired people for office jobs and forced them to do hard labor, Holmes was frequently threatening, McFarland did not pay local workers in Exuma), no or little experience in the industries they wanted to disrupt (Neumann had been a landlord for one floor of a building before starting WeWork, Holmes came with a background in chemical engineering undergrad training which she never finished, McFarland had never organized a musical festival before), middle class upbringing (Neumann’s parents were doctors, Holmes’s worked in the government, McFarland’s were real estate developers), using family and friends for early funding (Neumann through his wife Rebekah Paltrow and the connections he made at the Kabbalah center, Holmes through her family friends such as Tim Draper and Victor Palmieri), nepotism (Neumann employed his wife, sister and brother in law, Holmes installed her brother and his fraternity brothers at Theranos), and lots of charisma. There was even overlap between Neumann and Billy McFarland. McFarland had started his first company out of a WeWork office.

There were a lot of dissimilarities too. Neumann fudged numbers, but Holmes outright lied to people about her technology and what it could achieve, possibly harming cancer patients. Neumann had a major benefactor, Masayoshi Son, who invested billions in WeWork, an opportunity that Holmes did not get but more on Holmes later.

Neumann wanted to disrupt an industry that he did not understand well and which may or may not need to be “disrupted.” WeWork was a lousy landlord that provided small spaces for high prices with the promise of ‘community building’ in the form of common areas, beer on tap, and fancy coffee. Neumann tried to frame it as a tech company even though there was little to no technology involved in this operation. He wanted to ride the wave of success that tech companies were on. Unfortunately for him, he believed in his own bullshit. At its height, WeWork was opening up a new co-working location every day. By the summer of 2019, WeWork had 528 in 29 countries. The company had raised $12.8 billion but was losing $219,000 an hour.

The person who I find the most similar to Adam Neumann is, ironically, Donald Trump. They share many traits such as megalomania, exploiting their employees, hypocrisy (implementing vegetarianism at WeWork while having Lamb dinners), nepotism, fondness for opulence (Private jets, fancy cars), self-dealing (Neumann buying buildings and renting them to WeWork), showmanship, wanting absolute power, and expanding their brand outside their areas of expertise. The final days of Neumann at WeWork are reminiscent of the final days of the Trump presidency: everyone around Neumann knew that the jig was up, but they were too afraid to say anything. There is still litigation going on about his exit.

The tale of WeWork’s rise and fall is also the story of how venture capitalists (V.C.s) have taken over the startup world. In a NewYorker story titled “How Venture Capitalists are deforming capitalism“, Charles Duhigg wrote that ‘Whereas venture capitalists like Tom Perkins once prided themselves on installing good governance and closely monitoring companies, V.C.s today are more likely to encourage entrepreneurs’ undisciplined eccentricities.’ He writes at length about what happened at WeWork once the leash was off:

“WeWork had a number of internal problems that should have concerned Dunlevie and the other board members. In the spring of 2018, the board learned that a senior vice-president had prepared a lawsuit accusing a colleague of giving her a date-rape drug. She also alleged that executives often referred to female co-workers with such epithets as ‘bitch,’ ‘slut,’ and ‘whore.’ (The senior vice-president received a settlement, and the suit was not filed; Dunlevie told me that he has no recollection of the complaint.) There were reports, too, of top executives using cocaine at events, dating subordinates, and sending texts like ‘I think I should sleep with a WeWork employee.’ Some board members knew that Neumann used drugs, that he had once punched his personal trainer during a workout session in his office, and that a raucous party in Neumann’s office had ended with a glass wall shattered by a tequila bottle.

The board had also allowed Neumann, a passionate surfer, to take thirteen million dollars in WeWork funds and invest them in a company that made artificial-wave pools, even though surfing had nothing to do with WeWork’s business. Neumann spent millions more to finance an idea from Laird Hamilton, a professional surfer, to manufacture ‘performance mushrooms.’ The board knew that WeWork had spent sixty million dollars on a corporate jet, which Neumann and his family took to various surf spots. It had stood by as WeWork’s name was changed to the We Company; not long afterward, the company paid Neumann $5.9 million in stock because he had trademarked the word ‘We.’ (The payment was later returned.)”

For decades, venture capitalists have succeeded in defining themselves as judicious meritocrats who direct money to those who will use it best. But examples like WeWork make it harder to believe that V.C.s help balance greedy impulses with enlightened innovation. Rather, V.C.s seem to embody the cynical shape of modern capitalism, which too often rewards crafty middlemen and bombastic charlatans rather than hardworking employees and creative businesspeople.

———————————————————————————————–

“I tend to be wary of charismatic people. My father always reminded me that Ted Bundy was also very charismatic”. A former WeWork employee on the podcast WeCrushed.

There is an alphabet soup of regulators and regulations that governs laboratory medicine in the United States, including but not limited to FDA, CMS, CAP, AABB, Joint Commission, CLIA, and so on. Devices in a laboratory are regulated by the FDA. Any new device that one brings on or any new testing methodology that one wants to start requires permission from the FDA. Recently, many labs have applied for or received emergency use authorizations (EUA) from the FDA for their lab-developed tests (LDTs). Getting a full authorization for an LDT is a painstaking and tedious process involving loads of paperwork, which hindered the early rollout of COVID testing in the U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is responsible for regulating lab personnel and effective running of testing. They have approved some organizations such as The Joint Commission (TJC), CAP, or AABB to do inspections on their behalf. A lab director (M.D. or Ph.D.) has to get licensed to work as the lab director, and the buck stops with them. College of American Pathologists (CAP) is one of the leading organizations in the U.S. that inspects and provides guidelines to pathology labs. CAP is mentioned in the book ‘Bad blood’ by John Carreyrou inaccurately as the “medical association representing laboratory scientists”. CAP is an association of board-certified pathologists who are distinct from medical lab scientists (MLS).

Theranos considered itself above all these regulations. They constantly lied and manipulated data to satisfy the minimum requirements for getting their lab registered. They showed a running loop of pre-recorded videos to Novartis that showed blood flowing their cartridge and getting tests done for their Theranos 1.0 machine, in order to sell their product. Holmes was not trained in pathology, not even biology. She came with an unfinished bachelors degree in chemical engineering. Holmes’s mind veered from idea to idea until something stuck. She started Theranos initially to develop a wrist-worn device that analyzed a person’s blood, then switched to using small amounts of blood for lab testing and wanted to deploy it to help cancer patients, then to use the same technology to detect swine flu, to use the same technology to assist the US military in Afghanistan and Iraq, and to have her machines in Safeway and Walgreens.

Holmes was a control freak. She would ask anyone visiting the Theranos offices to sign an NDA first, this included all employees as well. She would pit one team of engineers against another for similar tasks. She appointed people to keep an eye on when employees came to work and left. In a tactic also used by WeWork, Holmes would order dinner frequently that arrived at eight o clock at night, ensuring that employees stayed late. Anyone who dared dissent was purged from the company without explanation. There was a lot of staff turnover at Theranos during its existence. There was a lot of hype created by Elizabeth, using her idea as revolutionary and selling it to gain reputation and money while actually delivering nothing. Along the way, she fooled V.Cs, CEOs of Pfizer/Safeway/Walgreens, General Mattis, Herny Kissinger, Rupert Murdoch, Larry Ellison, and David Boies.

These two stories illustrate two ambitious millennials who wanted to change the world, fooled enough people, spent billions of dollars to achieve their dreams but ended up as cautionary tales. As old Abe Lincoln would say, “You can fool all the people some of the time and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time”.Good riddance Elizabeth Holmes and Adam Neumann.

Books and podcasts that I accessed while reading this piece, 1) Billion dollar loser by Reeves Wiedeman 2) Bad Blood by John Carreyrou 3) WeCrashed podcast 4) The Drop Out, podcast.

An article comparing WeWork and Theranos that complements this piece is from Bussiness Insider: https://www.businessinsider.com/with-wework-theranos-line-between-charm-and-fraud-doesnt-exist-2019-9

P.S I think Adam Driver should play Adam Neumann in the movie version of WeWork. Both of them have a military background, are very tall, and of course, charismatic.

Charles Cameron, a contributor to this weblog, and an early guest on our podcast has died after an illness. I do not know any details (I saw a Facebook post), but I felt that it was important to mention his passing since his contribution to this forum was appreciated, and from what I knew of him he seemed a man with a great heart and boundless curiosity.

Death is inevitable, and a part of life. We too shall pass in our own time. All we can hope for in this one life is to leave memories that honor what we stood for after we leave.

Why was he arrested?

He was protesting alongside his comrades against the arrest of PTM leader, Manzoor Pashteen. Pashteen galvanized the youth and adult population in former federally administered tribal areas (FATA) that border Afghanistan. The presence of PTM threatens the ‘national narrative’ put forth by Pakistani establishment that they ‘cleared’ FATA of all militants during the Zarb-e-Azab operation (2014-2017). PTM contends that during and after the operation, military demolished homes and business places of non-militants living there and killed (or facilitated the killing of) many tribesmen who were actually anti-militant (Pashteen wrote about this for the NYT, read here. )

Following Ammar’s arrest, there were more protests in different cities in Pakistan. In Faisalabad, many protestors were picked up by the police today for protesting against the arrest of Ammar, who was protesting the arrest of Manzoor Pashteen. This suppression of dissent is reminiscent of fascist regimes around the world. There are not a lot of people as well-read and politically conscious as Ammar and his fellow protestors and muzzling their voices by force merely exposes the fragility of the military’s narrative. The number of people who think like Ammar in Pakistan is probably less than five hundred. Compare that to the numerical strength of Army proper: half a million (and millions of admirers). Since January 2017, when bloggers were abducted by agencies (and later released), there has been an uptick in ‘disappearances’ of progressive activists and students. Due to the abovementioned numerical mismatch, these abductions don’t always get the media coverage they deserve, and mainstream political parties almost never defend these dissenters. In such dark times, just a safe release of these protestors would be a welcome step.

P.S A twitter thread of tributes to Ammar by creative comrades: https://twitter.com/tooba_sd/status/1224025720873275394?s=21

One of the weirdest emails I’ve ever received.

The insults directed to me by people who are Pakistani or by people who are Hindus are peculiar, because they presuppose a sense of communal identity which I mostly lack. Insults toward Bengalis and Muslims just leave me scratching my head. Also, now that I am no longer 15 I don’t think that the measure of a man is how much “pussy” they bag….

Last month BP received more traffic from India than the United States for the first time. Above you can see a three-year trendline of BP user growth. In a little over one year “Brown Pundits” in some form will have been around for 10 years…

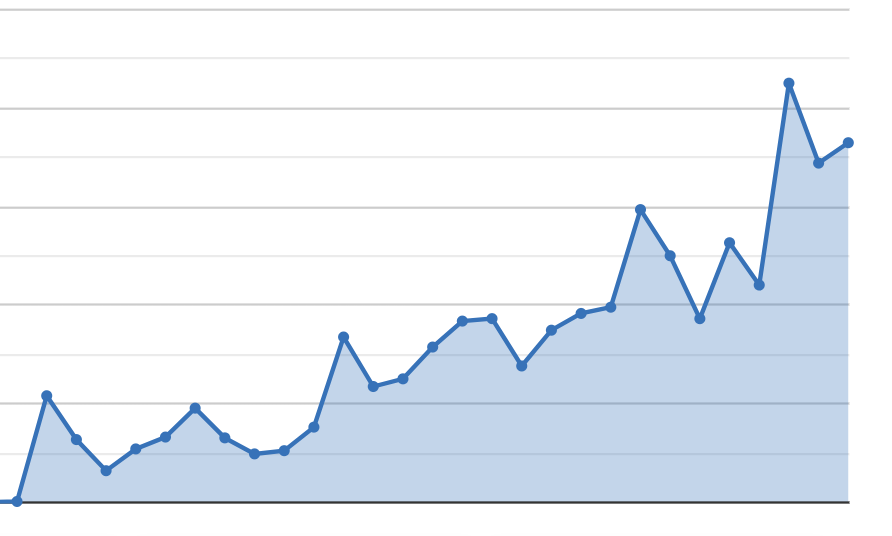

This weblog finally surpassed 1,000,000 pageviews after two years.

Above you can see the monthly trajectory of unique users who have visited per month since June of 2017. The “trendline” seems pretty consistent.

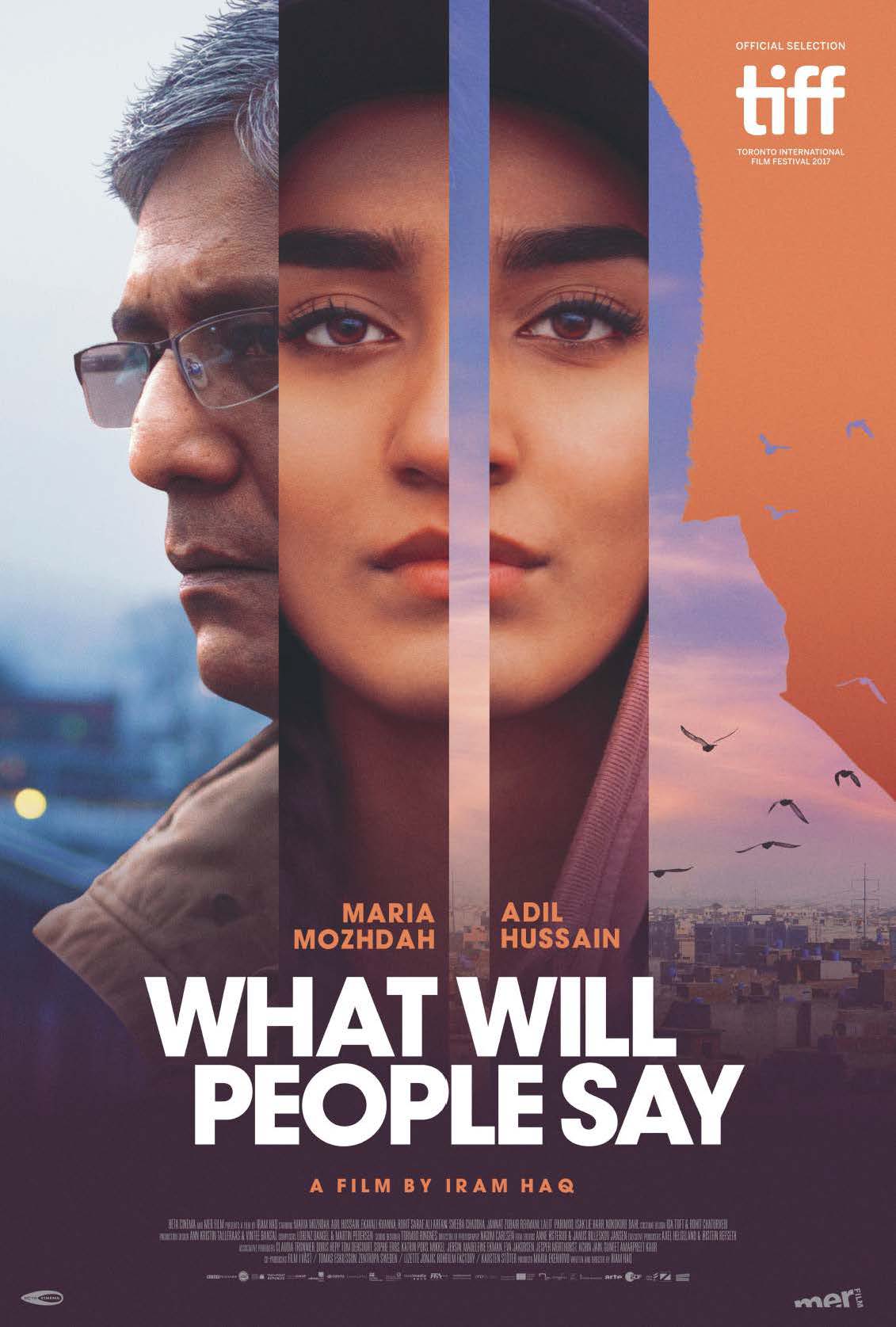

**Caution: Spoilers Ahead**

I was watching the film ‘What will people say’ (courtesy, Kanopy), an official selection at the Toronto film festival in 2018. It is a story familiar to anyone who grew up in Pakistan or in a desi family abroad. A young, second-generation Pakistani teenage girl (Nisha) in Norway wants to live her life like any other teenager in her peer group but is restricted by her parents. Like most rebellious teenagers anywhere in the world, she finds ways to do what she wants to do (go out partying with a friend in the middle of the night) but stops just shy of having physical relations with one of her guy friends. One such day, she gets caught by her father who finds one of her male Norwegian friends in her room and starts beating him and then turns his fury on her. A neighbor calls the police and Nisha is escorted to a safe place by Norway’s version of the CPS.

After spending a night at CPS, Nisha’s mother calls her to tell her that everything will be okay and that her father will pick her up from CPS in a few minutes. Nisha, being a teenager, falls for this trap. She ends up on a flight to Pakistan with her father. Her father leaves her at his sister’s house and returns to Norway the next day. Nisha tries to contact someone in Norway but she has no access to international calling or internet. Her first night, she tries to run away in the streets but comes back to find her aunt at the door telling her that the nearest airports in 350 Kilometers away. At another instance, she tries to send a message to one of her Norwegian friends via facebook through a net cafe but is caught and her Norwegian passport is burned. She spends eight months at that place. While she is there, she falls for one of her male cousins living in the same house.

One night, they are caught kissing at night by local police who beat him mercilessly and ask her to strip at gunpoint. The police then ask the guy to fondle her in front of them, all while taking photos of them. The couple is then dragged to their house and police demand money in exchange for deleting those photos. Nisha’s father is summoned from Norway by the Pakistani relatives and she is sent back. While Nisha’s father is in Pakistan, he spits at her face and then takes her in a taxi to the top of a mountain and orders her to jump from there. She tries to plead with him while he throttles her and tries to push her. He is unable to, and they end up back in Norway.

There is a family meal and her mother tells her that they are giving her a final chance. The prospect of her becoming a doctor is brought up and that it would be one way in which the honor of family can be redeemed. Some of the dialogues used by her mother upon her return are,

“People don’t even invite is to weddings anymore.”

“I wish you were stillborn”.

Within a few days of her return, she comes back from school to find that there is a ‘match’ ready to happen. The boy (Adnan) is a doctor in Canada and from a Pakistani family. Adnan’s aunt is visiting Nisha’s house and he is present via Skype.

Her father muses out loud that she can study and later work once she is in Canada. The boy’s aunt says ‘No, there is no need for studies or work. Adnan earns plenty of money. She’ll later be busy enough with children and the house”.

Nisha’s mother agrees with this statement.

After a brief chat, the ‘match’ is finalized and they are officially “engaged”. Sweets are consumed by everybody present (they are Pakistani, after all). The boy’s aunt then says, “Nisha, we are doing it only for your wellbeing”. The following night, Nisha, who had been rooming with her younger sister, decides to run away from the house again. It is snowing outside and before she leaves, her younger sister (who is about 6-9 years old) wakes up and sees her leave but doesn’t say a word. Once she has climbed down from her third story apartment, she walks towards the street outside their apartment complex and looks back. Her father is standing in the window, looking at her. Their eyes meet for a few moments and then Nisha takes off in the snow, running far away from the house. The End.

I thought the movie was generally well-made. There is some exoticization of Pakistan, as one expects in most films for a primarily western audience. The narrow streets, old houses, mountains in the background and a dilapidated bus, with Khawaja-siras (transgender people) selling boiled eggs to passengers, the old school vegetable and fruit market, classrooms without whiteboards and households without domestic servants. I read later that the story is loosely based on the life of its director, Iram Haq.

The premise, as I said earlier, is familiar to a Pakistani or a Pakistani-origin person. The rank hypocrisy of Pakistani society, the guilt-trapping (Pakistani parents’ favorite sport), violence in the name of honor and efforts to ‘save face’ in the community are daily realities of a desi household. While honor killings get splashed as headlines (deservedly), there is a lot of ‘micro-violence’ that happens every day in a middle-class Pakistani household with young girls (I’m talking about a representative sample). Some of the statements that I have bolded and put in quotation marks in the synopsis are familiar tropes of Pakistani parents, once they find out that the human being they created is not a robot that they can program. The situation, however, is much more dire for girls than it is for boys. Particularly when it happens abroad. One of my mentors used to say that Pakistanis in the diaspora tend to be normal people until their daughters start growing up. If it were up to Pakistani parents, they would bottle up puberty of their children and throw it away in the trash, instead of dealing with it like people everywhere else.

I write this not just as a commentator but as a witness. Both of my sisters, at different times in their lives, were ‘disciplined’ when they developed an interest in men that my parents had not chosen for them to marry. Sister number one was a teenager and had a crush on one of her teachers (which is the most teenager thing that I can think of). The guy in question used to visit our house for coaching (a normal occurrence for our household, to be clear) and he belonged to a lower-middle-class background. Once the ‘crush’ was discovered, he was banished from our house and my sister was warned never to mention his name again, or there would be dire consequences. She was 16 at the time. Around the time that she turned 17, she was engaged to a cousin who was studying abroad at the time. She got married at 18 and has lived abroad ever since. She has always been an obedient and slightly-passive child and has done okay in life, despite the obvious disadvantage.

Sister number 2 has always been a more outwardly emotional and strong character. Her first ‘issue’ arose during teenage years when she was found talking too many times with one of the male cousins. She would also ‘dress up’ (as much as one could in a provincial Punjabi town) when she went to coaching centers in the city during her high school years. Later, when she was in college, she needed some help with coursework and an acquaintance who worked in that profession was asked to help. The acquaintance deputed one of his juniors to help my sister. Fast forwards a few years and they were romantically involved. My parents were having none of that. They tried to ‘arrange’ her marriage at different places but she would stage some sort of stunt (act cold/be sarcastic/or just being rude) to get out of it. She tried to kill herself at least twice during this period. She was probably physically beaten more than once as well (I was at boarding school between 2000-2006 and in med school for 5 years after that so I only heard these things second-hand). I had met the dude in question and found him to be okay, nothing too spectacular or bad. As the firstborn male, I held a certain role in the family so I first cajoled my mother (who hated the guy partially because he was 10-12 years older than my sister and partially because he came from a lower-middle-class family and my sister has always had ‘high’ ambitions) and later my father (who felt guilty for having introduced the couple in the first place) and sister number 2 finally got married to him.

Were my parents monsters or merely representing the middle class, small-town, religious morality that they themselves grew up in? I don’t know the answer to that question. They are otherwise very decent, educated, ‘honorable’, pious people and a neutral observer meeting them for the first time won’t be able to see anything wrong outwardly. The pathos inflicting my parents is not restricted to them, it is shared by everyone around them, most of the society is rotten. And it’s not getting any better with time.

P.S A book that deals with issues of ‘honor’ in the Pakistani diaspora, particularly in Britain, is ‘Maps for lost lovers’ by Nadeem Aslam. One can also glean some knowledge about this from certain portions of the movie ‘Blinded by the Light’.