A review by my Uni batch mate, Sunil Koswatta

Charles Allen has written two books on The Buddha and the Sahibs and Ashoka—The Search for India’s Lost Emperor. The second book, written about a decade after the first one, is largely an expansion of the first.

Both are the stories of the “Orientalists” who discovered India’s lost history, the lost Emperor Ashoka, and the Buddha Dhamma that thrived in India during Ashoka’s time. Their methods of discovery were crude, sometimes outright criminal by today’s standards. However,there were honest“sahibs” who dedicated their whole lives to science and discovery; conversely, there were opportunistic and greedy “sahibs” whose only objective was wealth. Allen weaves his tale in a way to take the readers along with the discoverers while (mostly) permitting the readers to judge for themselves.

Among the most interesting are William “Oriental” Jones, who established the Asiatic Society of Bengal; James Prinsep, who deciphered Ashoka texts; George Turnour, who translated Mahawansa from Pali to English; Alexander Cunningham, who discovered many of the Buddhist pilgrimage sites; Dr. Waddell, who discovered Kapilavastu and Lumbini; and John Marshall, who finally introduced proper methods of archeological excavation.

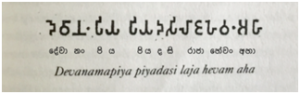

Prinsep worked to decipher the lettering on the pillar known as the “Feroz Shah’s Lat” or “Delhi No 1” for four years. His breakthrough came when he examined two dozen brief inscriptions of the same lettering at the Great Stupa at Sanchi. Prinsep guessed that these short inscriptions could only be records of donations. He was struck by the fact that almost all short transcripts ended with the same word with two characters: a snake-like squiggle and an inverted T followed by a single dot.

Here, he observed that the language was not Sanskrit but a vernacular modification of it, which had been fortunately preserved in Pali scriptures of Ceylon and Ava, a nineteenth century Burmese kingdom.Prinsep’sassistant with Pali was a Sinhalese named “Ratna Paula” (quite likely a corruption of the name “Rathanapala”).Both in Sanskrit and in Pali, the verb “to give” was “dana” and the noun “gift” or “donation” was “danaṁ” sharing the same Indo-European root as the Latin “donare” (to give) and “donus” (gift). This led to the recognition of the word “danaṁ,” teaching Prinsep the two letters, d and n of Brahmi 1. The snake-like squiggle represented the sound “da”, and the inverted T with the single dot the sound “naṁ.”

Too, Prinsep noticed that a single letter (like an inverted y) appeared frequently before or near the terminal word. Prinsep determined this letter to mean “of,” the equivalent of Pali “ssa,” based on his earlier investigations of the coins from Saurashtra. If his hunch was correct, then the general structure of each sentence was something like “So-and-so of the gift.”Prinsep’s translation of one such Sanchi inscription is “Isa-palitasa-cha Samanasa-cha danaṁ” (The gift of Isa-Palita and of Samana.)

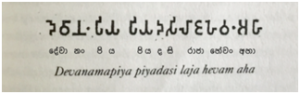

The opening sentence of Delhi No 1 had been observed to repeat itself again and again at the start of many sections or paragraphs of text in the pillar inscriptions and on the rock edicts. This,Prinsep could now read as “Devanampiyapiyadasi raja hevaṁ aha.” After conferring with Ratna Paula, Prinsep concluded that this opening phrase was best represented in English as “Thus spake King Piyadasi, Beloved of the Gods.” Prinsep published his findings in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in April, 1837.

But who was the author of these extraordinary edicts? Who wasPiyadasi? Prinsep couldn’t find a Piyadasi in all Hindu genealogical tables that he consulted. Only one possible candidate presented himself, one who had emerged from George Turnour’s translations of the Pali Chronicles of Ceylon: “King Devanampiatissa succeeded his father on the throne of Ceylon in the year of Buddha 236. He induced Dharmasoka, a sovereign of the many kingdoms into which Dambadiva was divided, and whose capital was Pataliputta, to depute his son Mahinda and his daughter Sangamitta, with several other principal priests to Anuradhapura for the purpose of introducing the religion of Buddha.”

In a letter sent to Prinsep on June 6th of 1837, Turnour excitedly revealed the identity of Piyadasi. “I have made a most important discovery. You will find in the introduction to my Epitome that a valuable collection of Pali works was brought back to Ceylon from Siam, by George Nodaris, mudaliar in 1812. This collection of Pali texts included a copy of the Island Chronicle, the original chronicle from which the later Great Dynastic Chronicle took its earliest historical material, but a less corrupted version—and with crucial differences. While casually turning the leaves of the manuscript I had hit upon an entirely new passage relating to the identity of Piyadasi … who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and own son of Bindusara, was at the time Viceroy of Ujjayani.”

King Devanmpriya Piyadasi of the Feroz Shar Lat inscription (Delhi 1) was not King Devanampiathissa of Lanka, as Prinsep had assumed. He was his Indian contemporary Ashoka Maurya.

After Prinsep’s death his work was continued. Alexander Cunningham relied on the accounts of the Chinese pilgrims Faxian and Xuanzang to discover the Buddhist pilgrim sites. Faxian’s Records of Buddhist Kingdoms was translated in 1836, and Xuanzang’s History of the Life of Xuanzang and His Travels in India was translated in 1853. Faxian, who travelled to India in 400 CE, identified Ashoka as Wuyou Wang (The King Not Feeling Sorrow). Faxian visited Sankisa, and Lumbini, and from Lumbini travelled south to cross the Ganges at the point he describes as “the confluence of the five rivers,” just upstream of the capital of the country of Maghada: Pataliputra. Faxian describes Wuyou’s palace and his towering city walls and gates as being inlaid with sculpture-work. About two hundred years later, when Xuanzang arrived, the Buddha Dhamma was in decline and the Pataliputra was all but abandoned. Cunningham conducted his field surveys with copies of Faxian’s andXuanzang’s travels in his knapsack. He tracked down almost all sites visited by the Chinese pilgrims, including Sravasti, Kosambi, Ayodya, Sankisa, Taxila, and Nalanda.

However, Cunningham assumed that Pataliputra must have been swept away by the changing course of the Ganges. Dr. Waddell thought otherwise. Taking together both Faxian and Xuanzang accounts,Waddell prepared a chart of Ashoka’s palaces and other chief monuments, and his chart led him over a railway line that marked the southern limits of “old” Patna, to a series of mounds known as Panch Pahari or the Five Brothers. He wrote afterwards, “I was surprised to find most of the leading landmarks of Ashoka’s palaces, monasteries, and other monuments when reexamined so very obvious that I was able in the short space of one day to identify many of them beyond all doubt.” Around the modern village Kumrahar, Waddell found various fragments of sculpture and other confirmatory details and learned from the villagers that whenever they sunk wells, they stuck massive wooden beams at a depth of about 20 feet beneath the ground. Megasthenes, a Greek diplomat who stayed at Pataliputra for six months during the Emperor Chandragupta’s reign, had recorded that Pataliputra was surrounded by wooden walls.

As mentioned before, not all sahibs treated their objects respectfully. James Campbell, the Commissioner of Customs, Salt, Opium and Akbari in Bombay Presidency in the 1890s, excavated several sites in Gujarat. Among his early triumphs was finding a new Ashokan rock edict, which he had allowed to be taken to bits, mislaid, and lost. A relic subsequently identified by the accompanying inscription as a segment of Buddha’s alms bowl was thrown away. He then moved on to tear apart the “Girnar Mound,” a large stupa a few miles south of the famous Girnar rock inscription.

In spite of some irresponsibility, all of these men contributed to the rediscovery of India’s past. The books that tell their stories are excellent, and in this reviewer’s judgment both belong in any Sri Lankan’s private library.

Sunil Koswatta

how the separatist movement evolved. The latter chapters are on the dynamics of the Tamil Diaspora in Norway. The excerpts are from that part of of the book.

how the separatist movement evolved. The latter chapters are on the dynamics of the Tamil Diaspora in Norway. The excerpts are from that part of of the book.