Script for the Youtube Video:

Script for the Youtube Video:

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode, Omar and Mukunda talk to Hussein Ibish about the recent events in Syria and their impact on the Middle east. Interestingly, Hussein mentions India as a potential host for Iranian uranium if a new deal is to be made..

Our friends at scribebuddy.com have prepared a transcript. I am posting it below, unedited.

Dr. Ali: Good evening, everyone, and welcome to another episode of the Brown Pundits broadcast. We have with us again 1 of our guests, Hossam Aibish. Mr. Aibish is a resident fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, and he is a regular columnist for The National in UAE. He writes for several other publications, has hundreds of speeches and videos, is a very well-known commentator on Middle Eastern issues. Continue reading Browncast: Hussein Ibish on Middle East

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode of Browncast, Gaurav and KJ talk to Indian Mango and Nitesh about the Landslide in the Maharashtra assembly elections 2024.

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this chat our 2 Resident US citizens and 2 Indians analyze US elections and its implications

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode KJ and Gaurav talk to a Marathi commentator from Marathwada-Vidarbha region about upcoming MH elections and the role of Maratha politics in it.

Please find the earlier review of the same novel i wrote a few years back: Parva: An epic masterpiece – Brown Pundits

Spoilers ahead

Continue reading A civilization born in blood : a relook at the final act of Parva

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

Modi does the unthinkable – goes to polls with a non-populist (revdi-free) budget

At the start of this year, I had written about Modi’s excellent economic stewardship during his second term amidst a period of extreme economic turbulence globally – a once-in-a-century pandemic followed by a major war which roiled energy markets and rapid rate hikes in the West to combat inflation (Modi’s fiscal masterclass). I had noted then that Modi:

“has achieved the near impossible of following a disciplined fiscal policy while not just maintaining his political capital, actually expanding it”

But I had fully expected that he would open up the purse strings during the election year budget this February notwithstanding his public remonstrations against the growing revdi (freebies) culture. And for good reasons. One, Modi had gone in for a ‘revdi’ at the end of his first term in 2019 (the cash transfer scheme for 120 million farmers). And the economic scenario in 2024 was decidedly more mixed compared to 2019 with greater level of economic distress among the poor. Two, recent state elections had seen parties winning based on extremely aggressive freebie promises. For example, Congress won handsomely in Karnataka last year with promises of a slew of freebies (or welfare programs if you like) amounting to more than 2% of the state’s GDP. So I must not have been the only person who was stunned to see that Modi had decided that the normal rules of politics does not apply to him. And as of today, his judgment appears to be spot-on because the only debate about the 2024 elections appears to be what his margin of victory will be. The reasons for this – the so-called “akshat-wave” after the Ram mandir inauguration, the opposition being in absolute shambles, the ever-increasing political stature of Modi – calls for a separate discussion. In this post, I peer into the future and see what Modi’s fiscal statesmanship could potentially mean for the country.

A 10-year long fiscal tapasya….

For reasons that are not entirely clear, fiscal conservatism has been an article of faith for Modi throughout his career as an administrator. He has held on to it steadfastly during his entire 10 years as the the Prime Minister. For anyone familiar with Indian politics, it is easy to appreciate how challenging it can be to stick to fiscal discipline even during times of buoyant revenues. This makes his unrelenting fiscal focus all the more remarkable considering that for most of his tenure, he has been hemmed in by weak tax revenues. Therefore, to call Modi’s 10 year long commitment to financial discipline as a tapasya (penance) would not be out of place.

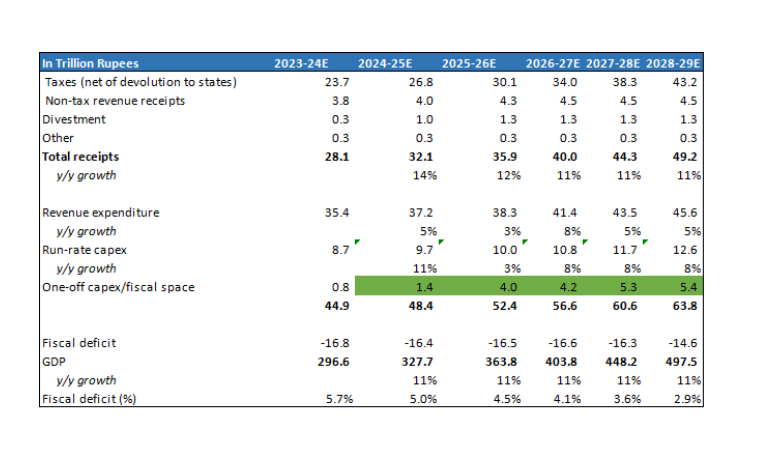

…might finally yield a Rs.20T (~$50bn) -sized fruit during Modi-3

And Modi is on the cusp of reaping the fruits of that tapasya in his third term. Barring unexpected shocks – electoral and economic – he could be presiding over a period where the economy has sizeable fiscal resources to pursue its socio-economic goals; a rare event in independent India’s economic history. Underpinned by a solid cyclical recovery in the economy and strong buoyancy in tax collections (direct taxes likely grew at 20% in 2023-24, twice the pace of nominal GDP growth), Modi-3 is not only placed very comfortably to meets its 2025-26 fiscal deficit target of 4.5% (vs. 5.8% in 2023-24), it will also have its disposal, up to Rs.4 trillion of fiscal space during 2025-26 for spending on new programs or projects (or >1% of GDP) after meeting its regular revenue and capital expenditure obligations. That is the base case which assumes direct taxes grow at 15% annually. In a bull case of direct taxes continuing to grow at 20%, the above figure could be as high as Rs. 5.5 trillion. Further, this figure will continue to swell with each succeeding year as the economy expands and revenue growth outpaces the growth in base expenditure. During Modi’s third term, I estimate that the central government will have up to Rs.20 trillion of aggregate fiscal space for new programs/projects. Also, note that many of the programs of the central government include contribution from the states, which means the total fiscal resources available could be well higher than Rs. 20 trillion.

(For those interested in the math behind the above numbers, I discuss the same at the end of the post) .

Potentially transformative, but availability of funds is not enough

What can one do with an annual budget of Rs.4 trillion? Well, for perspective, the Jal Jeevan Mission which was initiated in Modi’s second term with an annual budget outlay of Rs.0.7T (Rs.3.5T over 5 years, 60% funded by centre) will have provided tap water connections to 160 million households by end of 2024 (110 million connections provided as of April 2024). No commentary required on how transformative this project has been for the 100s of millions of beneficiaries.

In the first two terms, Modi’s focus was primarily on building physical infrastcucture – road building under Gadkari has been an unqualified success while in case of Railways, huge investments have been made, it is still a work-in-progress with mixed results so far. Even welfare schemes had a physical asset bias – from toilets to piped water to housing. While the government deserves a lot of credit for strong execution, it has to be underlined that these are relatively low-hanging fruits from a governance perspective. As the priority areas inevitably shift from road and railways to more complex ones, quality of policymaking, human capital and management will be the key drivers of outcomes, and not just availability of funds. To wit, it is way more difficult to develop 20 high quality IITs or a few hundred Kendriya Vidyalayas compared to building 100K kms of roads. Or just throwing around money into PLIs will not deliver a successful industrial policy.

An opportunity for Modi to cement his legacy – a wide range of focus areas to choose from

What areas Modi will prioritize with the Rs.4 trillion per year (~$50bn) of additional resources is anyone’s guess because this is one government which revels in keeping its plans a total secret. One can only say two things with certainty -one, Modi will be extremely keen to cement his legacy with a couple of flagship projects/programs which has a transformational impact on society. Two, the consummate politician that he is, he will have his eyes firmly on what programs will drive the optimal political benefit for the 2029 elections (and all the state elections over the next few years).

The list of potential programs is endless. Below, I discuss briefly a few ones which I see as critical ones. I classify them into 3 categories: A) long term strategic B) medium term economic growth and C) quality of life. Obviously, most of these programs will tick all three boxes, the classification is based on how a politician like Modi would want to see it. Admittedly, some of the resources might also simply get used up in standard fiscal management as well – ie Modi might simply want to reduce fiscal deficit at a faster pace, or execute the long pending reduction on tax surcharges on the rich or fill up the job vacancies in the government.

The second part is investment in energy transition. So far, the Modi government has bet big on solar but now it has also stated its intention of expanding its nuclear fleet (add 15 GW by 2030). While investments in solar power has been largely driven by private players, the government will need to play a big role in setting up nuclear plants. A back-of-envelope estimate for the cost of the plants would be $50 billion and it would be reasonable to assume that the government will have to invest close to half of that amount.

The fiscal math

Assumptions

Fiscal deficit falls to 4.5% by 2025-26 and below 3% by 2028-29.

A few points:

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

Fiscal management has been one of the most critical parameters for evaluating the central government’s economic governance as far back as I can remember — and I have been a amateur observer of the Indian economy for more than two decades. And not without reason. In the Indian context, fiscal management goes well beyond the classical approach of fiscal as a countercyclical force — i.e. government spends more during economic downturns and dials back when the economy is doing well. For India, there has been a strong case for a structural reduction in the government’s fiscal deficit primarily for the following reasons:

A) The most obvious reason — uncontrolled fiscal deficit can result in a debt trap. The Indian government has already been spending between one-third and half of its total receipts towards interest payments since 2000.

B) The fiscal deficit is funded by borrowings in the domestic market. This in turn, crowds out investment by private sector who are competing for the same funds.

C) High fiscal deficit risks macro-economic instability — high inflation and a Balance of Payments (or foreign exchange) crisis . High government spending flows into higher income for households which drives higher consumption demand. If there is not enough supply, it leads to inflation. If you think about it, it is related to B). It boils down to the fact , in many instances, government spending is not economically efficient and therefore is not generating commensurate economic output.

Indeed, we saw the macro-economic instability play out in UPA 2 as high fiscal deficit contributed to persistently high inflation, an out-of-control trade deficit (imports less exports of goods and services).

That being said, economic theory is not like the laws of physics. There are those who have argued that both During the Vajpayee and Modi years, the governments missed a trick by being too fiscally conservative and thereby stifling growth. But even most of these critics argue only about the scale of fiscal tightening, not the principle itself that fiscal tightening is a good for the long term.

As is to be expected, the ideal amount that any government would prefer to spend is…….infinite. The more a government spends, the more popular it will be with the voters, in the near term at least. Fiscal management for a ruling party, therefore is a tightrope walk between preserving one’s political capital and an economically optimal fiscal policy.

In these series of posts, I plan to analyse Modi’s record of fiscal management during his second term. I posit that Modi has delivered a masterclass in fiscal management — he has achieved the near impossible of following a disciplined fiscal policy while not just maintaining his political capital, actually expanding it. All this, amidst times of high economic turbulence globally. In good part, this is because we have, arguably the most incompetent and out-of-touch opposition since independence. But this is also a story of how a politician put his popularity at stake and took the more difficult economic path and the average voters’ willingness to look past their near term pain due to their abiding faith in the man’s intention (the Hindi word is neeyat, I think) and ability to deliver in the long-term**. That is what it is all about — because let us be honest, Modi has, after all, not delivered all that well in terms of the promise of acche din so far.

**Critics will argue this is because voters are prioritizing Hindutva over economic development. There is some truth to it as well and as a Hindutva supporter, I see it as a good thing. But I believe they are exaggerating the Hindutva factor but that is a separate debate.

Fiscal deficit is simply the difference between the total expenditure of a government and its total receipts. This is typically measured as a percentage of GDP.

Both expenditure and receipts are classified as revenue and capital. A capital expenditure is something which results in the creation of a long term asset — a road, a railway track, a port and so on. Spend which does not result in a long term asset is revenue expenditure — things like salaries for government employees, fertilizer subsidy given to farmers, interest on borrowings etc. Revenue receipts are primarily either taxes or dividends from government-owned companies or from RBI. Capital receipts are inflows from divestment of government companies, sale of telecom spectrum etc.

Revenue deficit is the revenue expenditure less revenue receipts. Again, this is measured as a % of GDP.

Total debt as a % of GDP is another key measure of fiscal management, which is self-explanatory.

Internal and Extra Budgetary Resources (IEBR): The government can also spend money outside its budget books via the companies that it owns. For example, if NHAI takes a Rs. 1 lakh crore loan to build roads, that borrowing will not be reflected in the government’s books. But ultimately the government is responsible for the debt, so it needs to be factored in.

Quality of spend — revenue vs capital expenditure

It is generally understood that, in the Indian context, the government should be spending more on capex considering how deficient we are in terms of infrastructure. And on the other hand, contain revenue expenditure which is a less efficient use of fiscal resources. But this is just a high-level view and I will have to warn upfront that not all revenue expenditure is bad and not all capex is good. For example, this government is spending 70K crores this year on Jal Jeevan Mission — all of this is revenue spend. On the other hand, the government has allocated over 50k crores as capital infusion to BSNL. Difficult to argue that this is actually for the creation of productive assets and not just covering the losses an inefficient public sector operator.

But for a big picture view, we assume that capex spend is qualitatively better and then as I drill down further, we look more closely at the specific areas of spend.

What is good fiscal management?

Tax revenues, which constitute the bulk of total receipts, are generally a function of the economic cycle. The government can, of course, raise or lower tax rates. Further, in the Indian context, growth in tax revenues also reflects on the effectiveness of the government’s taxation policies and administration in bringing in greater formalisation of the economy (what is called bringing black money into the tax net, in popular parlance).

Most of the revenue expenditure is either non-discretionary or semi-discretionary. Whether the economy grows 8% or declines 6% (like in 2020–21), one will have to pay the salaries, service the debt and so on. Even spend that is discretionary on paper, is de facto non-discretionary. No political party will touch the fertlizer subsidy, for example. Further, there is constant political pressure to increase revenue spend because that is an easier way to reap political dividends. On the other hand, while capex is discretionary, it is also critical for the long term.

The performance should therefore broadly be judged on the following parameters:

A) What is the overall level of fiscal deficit? With the caveat that it should be seen in the changed global context due to a once-in-a-century pandemic.

B) Receipts growth and especially tax buoyancy — ie how much has tax collection growth out/underperformed economic growth?

C) Quality of expenditure — Ability to keep revenue expenditure in check and focus resources on capex.

But I cannot emphasize enough that good fiscal management is the ability to balance the above political vs economic imperatives in an optimal way. A good example of how not to do it was provided by the BJP government in Karnataka which went to polls last year boasting of a disciplined fisc and record capex allocation, only to be swept away by the voters who chose the opposition party which announced a slew of pro-poor welfare measures (or freebies or revdis, as critics would call it).

Alright, now we get down to the numbers. Here, I analyse Modi’s fiscal management at a high level for the period 2019–20 to 2023–24. Keep in mind that we had a major global pandemic which dramatically pulled down economic growth the world over and this also meant governments had to expand their fiscal spend substantially. So fiscal metrics go awry — higher numerator and lower denominator (i.e. GDP).

Fiscal deficit expands, as pandemic hits growth

Modi started his second term with a fiscal deficit of 3.4% (2018–19), which was quite moderate then, but looks like an unreal number in a post-pandemic world. The number is also low because a good part of the spending was done via IEBR (ie outside the budget books). He will end the term with a fiscal deficit of close to 6%, which is a pretty good performance overall, considering how the pandemic has ravaged public finances worldwide.

GDP during the period grew at just 4.2% annually. If expenses grow faster than GDP growth, it leads to a widening of fiscal deficit while if it is slower, it leads to a reduction. The converse is true in case of receipts. As you can see in the table below, receipts grew only modestly faster than GDP, so the widening of the fiscal deficit is largely attirbutable to higher expenditure.

Note: 2018–19 GDP has been indexed to 1000 and all figures are based on real growth (i.e adjusted for inflation)

Budgetary capex spend grows sharply

Next, we drill down to the expenditure. What do we find? Both revenue and capital expenditure has outpaced GDP growth but it is capex which has grown at a furious pace. But since revenue expenditure accounts for more than 4/5 of total spend, it contributes to 100 bps (100 bps = 1%) of the widening in fiscal deficit while capex contributes to 170 bps.

Capex spend trend solid even after factoring in IEBR

But wait, the capex growth is not as dramatic as it sounds. A large part is simply because Modi government moved from IEBR to budgetary support for road and railway capex. Combining both budgetary capex and IEBR spend, the numbers still look pretty solid though. Optically, it increases only by 20 bps to 5.0% but 2018–19 was also an extremely strong year for capex spend. If one compares the overall capex spend for Modi’s first and second term, the trend of improving capex spend is clear. And this is during a period of aneamic revenue growth.

The fiscal masterclass — strong discipline in revenue spend (ex-interest)

Drilling down further into revenue expenditure, we find that the increase in spend has been entirely driven by higher interest expense. This is because, like most other governments, India had to suffer big fiscal deficits in the first two years of the pandemic — so higher overall debt levels. This was further exacerbated by rising global interest rates.

Excluding interest expense, revenue expenditure has actually been a net positive for the fiscal deficit, moving down by 40 bps. This forms the crux of the fiscal masterclass that I keep referring to. In a period of economic turmoil, Modi government has been able to hold the line on revenue spend, amidst immense political pressure for populist measures. Revenue expenditure (ex-interest) annual growth was contained at just 3.2% — we will drill down further on this later but this low growth is despite significantly higher outlay for food subsidies and the Kisan DBT (2019–20 was first full year of the program).

Receipts — modest growth supported by high fuel taxes

Receipts have only modestly outperformed GDP growth though we are finally seeing signs of a turnaround in private sector profits as the sector comes out of the twin balance sheet crisis (high bad loans in banks and high debt levels in businesses). Meanwhile, Modi has held the line with high fuel taxes, inarguably an unpopular decision politically. While it was easier to do when oil prices had collapsed in 2020, to continue those taxes even as oil has moved back to $80/bbl shows great political fortitude. And he has maintained those high taxes with just a few months to go for the national election.

(On a tangent, I have written about why fuel prices should be reduced and it has no impact on the fisc)

Higher fiscal deficit but fiscal internals and outlook positive

To summarize, fiscal deficit widened by 250 bps during Modi’s second term but this was driven by a 170 bps increase due to capex and 150 bps increase due to higher interest expense. Revenue expenditure (ex-interest) actually came down by 40 bps.

Admittedly, a fiscal deficit of 5.9% is still quite high but the government has set itself up pretty well for a meaningful reduction in the medium term. For one, there are clear signs of a corporate profit recovery and strong bouyancy in personal tax collections. Two, the burden of interest expense should keep progressively coming down given an exapnding GDP base. Three, the government has the option of flexing down on capex spending over the next couple of years contingent on a revival in private capex spend.

Counterfactual — what if it was UPA-3 instead of Modi-2

One way to think of the scale of Modi’s achievement is to think where the fiscal deficit would have been if we had a UPA-3 in 2019 instead of Modi-2. How much higher would the revenue expenditure spend have been? And how much lower would the fuel taxes have been? And what that would have translated into in terms of fiscal deficit, inflation and growth. Admittedly, the difference between a UPA-3 and Modi-2 does not just boil down to Modi — a large part is simply because BJP has a majority while UPA would have been an unstable coalition. But, again Modi deserves a lot of credit for running the first non-Congress majority government.

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

I flooded the TL with tweets on the budget today. Putting it all together in one place for future reference.

1) The big takeaway — a stunningly non-populist budget in an election year

Unlike in 2019, when the government deliberately advanced the budget date by a month so they could announce a major welfare program (Kisan DBT) and tax cuts for middle class, which added up close to Rs.1 trillion of giveaways or roughly 0.5% of GDP, this budget had almost nothing at all for any section of the voters. This is even more remarkable because A) in the last few years, state elections have seen a strong trend of rampant freebie promises and B) the economic scenario is decidedly more mixed compared to 2019 with clear signs of K-shaped recovery and economic stress in the bottom half of the population. I would have thought Modi would go in for freebies at least comparable to 2019 (0.5% of GDP would be Rs.1.7 trillion), him choosing not to do so is a measure of the supreme confidence he has regarding 2024 elections.

https://twitter.com/Saiarav/status/1752943127965606319

Of course, Modi can still surprise all of us with an unexpected 8 PM announcement with a slew of welfare measures, in which case it will very likely include a large fuel price cut.

https://twitter.com/Saiarav/status/1752957283116663149

2) The fiscal glide path looks very promising; immense possibilities

The budget estimates for 2024–25 are extremely conservative, with some of it to the point of being ridiculous. Take the 2023–24 RE for corporate taxes for example — the underestimate of growth is silly, with just two months left for year-end, it kinda makes the budgeting exercise meaningless.

https://twitter.com/Saiarav/status/1752953035884741074

Apart from tax revenue figures, I see huge potential for large divestments in 2024–25 (budgeted to be just 50K cr) given how hot the markets are.

Further, nominal growth estimates are conservative as well… a larger denominator will also support a lower fiscal deficit.

https://twitter.com/Saiarav/status/1752956446457868299

Overall, I see higher direct tax collections and divestments resulting in at least a 20–30 bps beat over the 5.1% fiscal deficit target for 2024–25. And then we get to 4.0% by 2025–26. This is all very important for the economy — a potential upgrade in our sovereign credit ratings amidst expectation of greater FII investments in the domestic bond market, in turn leading lower interest rates.

The fact that we appeared to have dodged a new freebie program which will be a permanent burden on the resources drives immense possibilities. As the fiscal deficit comes under control, the government will have much greater resources to fund new priorities, beyond road and rail.

https://twitter.com/Saiarav/status/1753160724871057721

3) Capex spend continues to be solid

The 2023–24 RE for capex spend came in lighter than BE but this is, in large part, because the government shelved the plan for equity infusion into oil OMCs.

The IEBR RE figures were sharply below estimates but this is due to FCI borrowing less funds for its operations (which is a good thing).

One sizeable miss was lower railway IEBR capex — much lower spend on the DFC…apparently because part of the project got shelved.

Meanwhile, Gadkari seems to have no problem handling any amount of capex thrown at his department, solid execution.

For 2024–25, the capex budget is a 10% increase which is pretty good considering its coming off a very strong capex allocation in 2023–24.

4) Huge capital infusion into BSNL — strategic or a waste of taxpayer’s money?

Close to Rs.2 trillion will be infused into BSNL between 2022–23 and 2024–25. This is on top the spectrum it will get for free which as an opportunity cost, if my understanding is right. My initial take was that this was a waste of money into a loss-making, inefficient PSU but then I was told …

…that the capital infusion had a major strategic objective.

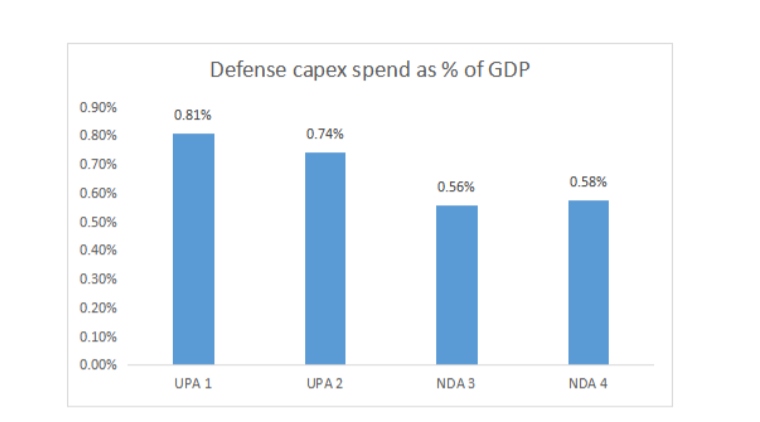

5) Defense capex continues to be weak

6) Postal department — yet another case of a broken public sector biz

7) Railway finances continues to be in shambles

I wrote, perhaps two dozen tweets on railways, so I will put that up as a separate blogpost…but the key takeaway, railway finances continue to be in shambles.

8) The difficult job of fiscal management — limited spending discretion

Most of the spend is just completely non-discretionary, minimal ability to cut cost, either for political or administrative reasons.

9) Energy sector capex — disappointing

The IEBR spend by Oil PSUs or capex for atomic energy is modest — remember there was a recent announcement of significant expansion plans in nuclear capacity thru 2030. Well, the money is not forthcoming.

10) What is going on with defense pensions?!? — very low allocation

11) Hits and misses on government spending estimates for 2023–24

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

The 1946 vote and the Muslim mandate for partition

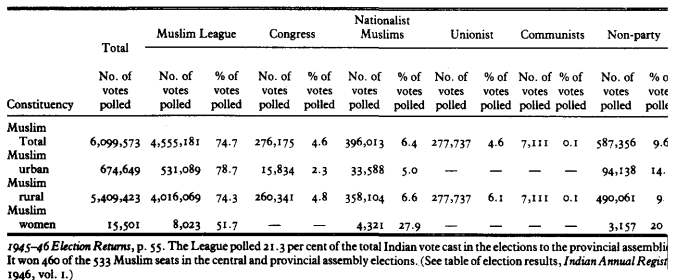

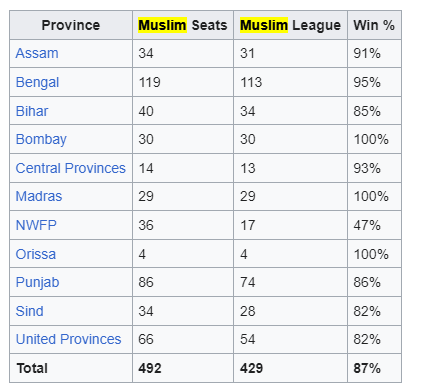

The 1946 elections remains inarguably the most consequential election within the Indian Subcontinent. Jinnah’s Muslim League (ML)went into the polls with a single-point agenda of partition and the Muslim voters responded with feverish enthusiasm, delivering a crushing victory for ML across all provinces, thereby paving the way for partition. The party won an overwhelming 75% of the Muslim votes and 87% of the Muslim seats, and except for NWFP, its minimum seat share was 82% (see table below). Of note, provinces from current day India -places like Bombay and Madras, which had zero chance of being part of a future Pakistan – gave a 100% mandate to Jinnah.

(for those who are not aware, we had a communal electorate at that time which meant Muslim voters would vote exclusively for Muslim seats)

Facts belie claims of Muslim society non-representation in mandate

As regarding the role (culpability?) of the Indian Muslim society in facilitating partition, establishment historians put forth two arguments. One, Jinnah had kept the Pakistan promise deliberately vague and hence the voters did not realise what they were voting for. Two, the overwhelming mandate from the voters cannot be taken as representative of the sentiments the whole society as only a tiny proportion of Muslims had the right to vote. The first one is a qualitative debate and can be debated endlessly. But the second assertion is easier to examine since we have actual voting and demographic data and that is what I will endeavour to do in this post. I reference one specific claim which is quite popular in social media — that the mandate was only from 14% Muslim adult population, based on an article written by a leading X handle, Rupa Subramanya, who has a rather interesting history with respect to her ideological leanings.

The analysis that follow will show that at least one adult member (mostly male) from close to 40% of the Muslim households in British Indian provinces and at least 25% of Muslim adults were eligible to vote .

I cannot emphasize enough that this is not something which should be used to question Indian Muslims of today. The founding fathers of the modern Indian nation made a solemn promise to Muslims that they will be equal citizens of this nation and that should be unconditionally honoured. But as a society, we should have the courage and honesty to acknowledge historical facts rather than seek to build communal peace on a foundation of lies, as the left historians have done; Noble intentions are not an excuse. Talking of fake history, one cannot but marvel at the sheer degree of control over the narrative of the establishment historians that they have managed to perpetrate the claim about the 1946 vote for more than seven decades when there is hard quantitative data available on number of voters, the country’s adult population etc. One can only imagine the kind of distortions they would have done to medieval history where obfuscation would have been infinitely easier.

Some basic facts about the 1946 elections

I will start off with some facts and estimates which are broadly indisputable.

A) The 1946 provincial elections was limited only to British Indian provinces

The 1946 elections was limited to provinces directly ruled by the British which accounted for roughly 3/4 of British India’s population. While the provincial representatives in turn elected 296 members of the Constituent Assembly, the princely states nominated 93 members the constituent assembly, i.e in proportion to their respective population. With ML bagging 73 of the 78 Muslim seats in CA, the partition debate was as good as sealed.

B) 28% of the adult population of the provinces was eligible to vote

The total strength of the electorate was 41.1 million voters while the total population of Indian provinces was 299 million. Taking into account only the adult population (age of 20+, ~50% of the population), it implied 28% of the population were eligible to vote.

(data is sourced from Kuwajima, Sho, Muslims, Nationalism and the Partition: 1946 Provincial Elections in India, Manohar, New Delhi, 1998, p. 47.)

C) An estimated 25% of the adult Muslim population of the provinces were eligible to vote

While I am unable to source the actual data for the percent of eligible voters within Muslim community, there is no reason to think it would be an order of magnitude lower than the overall 28% number. As I show in the Appendix, voter and turnout data indicates the number should be in the 25% range, if not higher; i.e. about 9 million Muslims out of 37 million adult Muslim population in the provinces were enfranchised.

D) Close to 40% of Muslim households had members eligible to vote

The 28%/25% voter ratio discussed above is skewed by the fact that very few women were allowed to vote. Only 9% of adult females had voting rights which in turn implied that 46% of adult males had voting rights. (Source: Kuwajima, Sho). If we assume the same proportion for Muslim females, that would imply little over 40% of Muslim adult males were enfranchised.

E) 75% of the 6 million Muslim votes went to ML

4.5 million Muslims voted for Muslim League out of a total 6 million Muslim votes cast from an electorate size of 9.2 million. Of note, there is no major urban-rural divide — the figure for rural areas is 74% vs 79% for urban areas.

Muslim mandate way more broadbased than projected in mainstream narrative

Based on the above data, at the very least, one has to concede that 25% of the Muslim society had a say on the issue of Pakistan and three-quarters of that group did vote for creation of an independent Muslim State. This severely undercuts the claim that only a tiny elite voted for Pakistan — Rupa’s 14% figure, for example, is clearly wrong **. But even the argument that the bottom 75% had no say on the issue is inaccurate because the voting rights were not just based on class, but also on gender. As noted above, close to 40% of adult male Muslims were enfranchised — in other words, 40% of Muslim households had an adult member who could vote. And of this 40%, three-fourths or 30% chose to vote for Pakistan. That clearly means that a much larger cross-section of the Muslim society had a say than just a tiny elite or the educated middle classes (or the salariat class as Ayesha Jalal calls it). This appears to be a more reasonable interpretation of a mandate given the context of the time when universal for women was still a new or evolving concept in many advanced democracies.

** The error that Rupa makes in arriving at the 14% figure is two-fold. One, she takes the adult Muslim population for entire British India (~44 million) whereas the elections were held only for provinces (~37 million). Second, she uses actual voter turnout (6 million) instead of the total size of the Muslim electorate (~9.2 million).

What are some of the counterarguments to the above interpretation?

A) What about the fact that the Muslims in princely states had no vote?

This argument, on the face of it, is not without merit. But one needs to be honest about framing it — this is not a case of a vertical class divide in enfranchisement but a horizontal regional divide. Therefore, the proponents of the non-representative nature of the mandate will have to make the case that the Muslim subjects of the princely states would have taken a significantly different view on Pakistan versus the ones in the provinces, just harping on the class divide will just not cut it.

Let us look at what the data can tell us. The adult Muslim population from the princely states would be another 8 million. Based on 1941 census data nearly 60% would be from three large states — Hyderabad (17%), Punjab (18%) and Kashmir (24%). Is there any reason to believe that the Muslims of Hyderabad or Punjab would have voted very differently versus their neighbor provinces of Madras Presidency or Punjab province? A debate on this issue is beyond the scope of this post but I would say that the burden is on those making the “non-representative mandate” argument to make that case.

For the record, if we take total Muslim population figure, then the proportion of adult and male adult enfranchisement of Muslim community would go down to 21% and 34% respectively

B) Muslim women were largely excluded

As noted earlier only about 9% of adult women were enfranchised. Assuming a similar (or lower) figure for Muslim women, indeed they had little say on the matter. One interesting aspect is that even among the Muslim women eligible to vote, very few seem to have turned up to vote. Only 15K of them voted which would be a turnout in the low single digits at best! But among those who did vote, more than 50% voted for ML, which is admittedly well below the overall support of 75%. But still, the fact is that a slim majority of Muslim women too voted for Pakistan. Also, electoral mandates need to be interpreted based on the context of that time and broadbased women suffrage was still at a relatively early stage even in more advanced democracies.

C) Hey! only 4.5 million out 37 million Muslim adults voted for ML

This would mean only 12% of adult Muslims expressed support for Pakistan. In a very narrow mathematical sense, this is, of course. right. But this is just not how electoral mandates are interpreted in any democracy. If one uses this yardstick, it would mean Presidents in one of the world’s oldest democracies, have been consistently elected with support of just a quarter of the electorate because voter turnout in US has generally been around 50%. The ones who had the right to vote but chose not to exercise it will need to be excluded from any interpretation of the mandate.

Conclusion — acknowledge history and move on

Partition has a cast a long shadow on Hindu-Muslim relationship and perhaps it was a wise decision in the immediate aftermath to underplay the Indian Muslim community’s role in it. But a fiction cannot be the basis for a permanent peace. At some point, we will all have to collectively acknowledge the historical facts and have the maturity to move on. One additional problem also is that this fictional narrative about the mandate further feeds into the Muslim victimhood that they had chosen a secular India over a Islamic Pakistan and have been betrayed by rising Hindu majoritarianism. A honest appraisal of history might perhaps lead to a more constructive political strategy.

Appendix — estimate of eligible voter percent within Muslim community

A) The Muslim population in the provinces was 79.4 million. Given higher birth rate among Muslims, the adult population is lower than the national average — using Pakistan’s 1951 census data as a proxy, I estimate the adult Muslim population to be 47% or 37 million.

B) Total number of Muslim votes cast was 6 million (Ayesha Jalal)

C) Average turnout across communities was around 65%

D) If one assumes a similar turnout for Muslims, then the total electoral size for Muslims comes to 9.2 million which implies 25% of adult Muslim population was eligible to vote. It is quite likely that the turnout was much lower because the turnout amongst Muslim women was abysmally low (Ayesha Jalal)

So it is reasonable to conclude that at least 25% of the adult Muslim population living in the provinces were enfranchised in 1946.