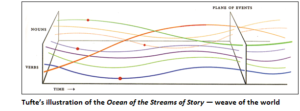

I was senior analyst in a small and wonderfully eccentric DC Beltway think tank a while back, and my boss kept asking me for what he called “early indicators” of upcoming troubles. The trouble was, I never saw an “indicator” as such — I only ever saw “indicators” plural. It takes two to tango, they say, and from my POV it takes two to make a pattern.

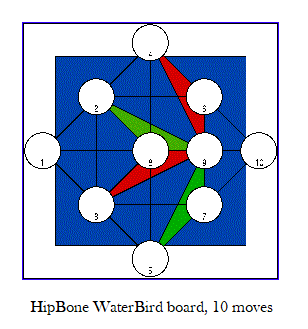

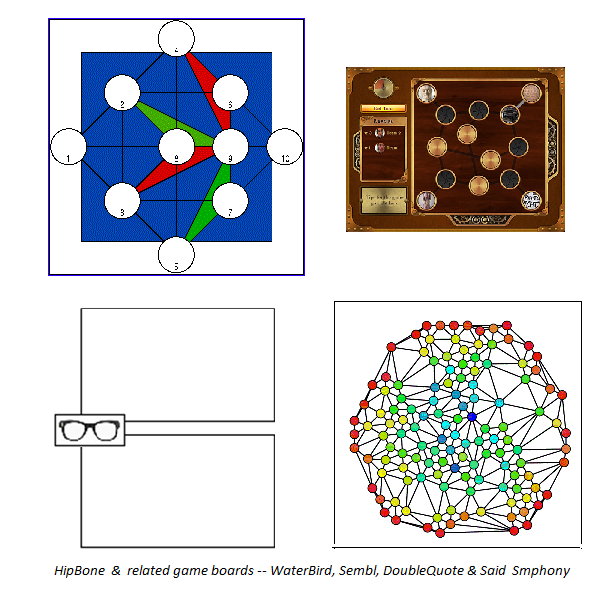

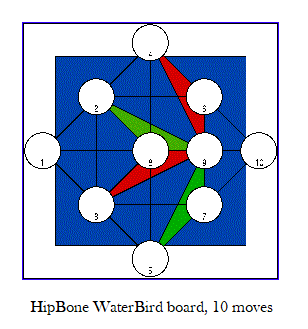

My HipBone Games began as an attempt to make Hermann Hesse’s Glass Bead Game playable, preferably on a paper napkin in a sidewalk cafe, so I began with boards like my WaterBird —

— with ten moves, ten concepts arrayed in such a way that players or later readers could see ten richly interconnected concepts in one place — concepts that might be textual, musical, mathematical, visual, filmic — if we’d known how to convey smells via the internet, I’d have included those, too..

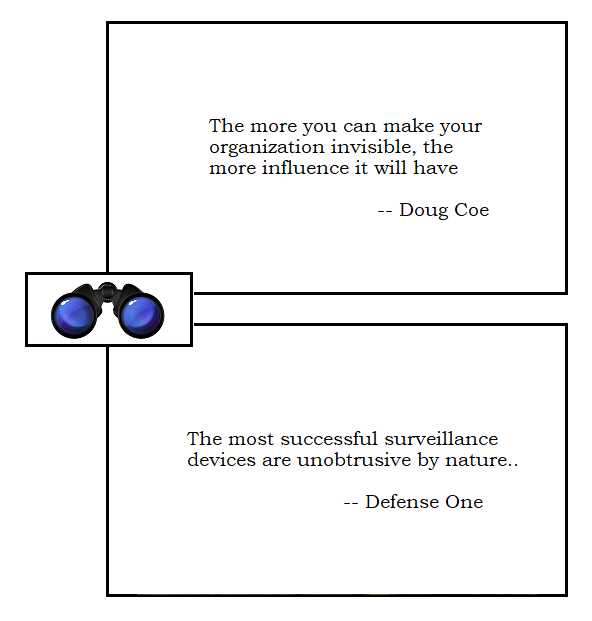

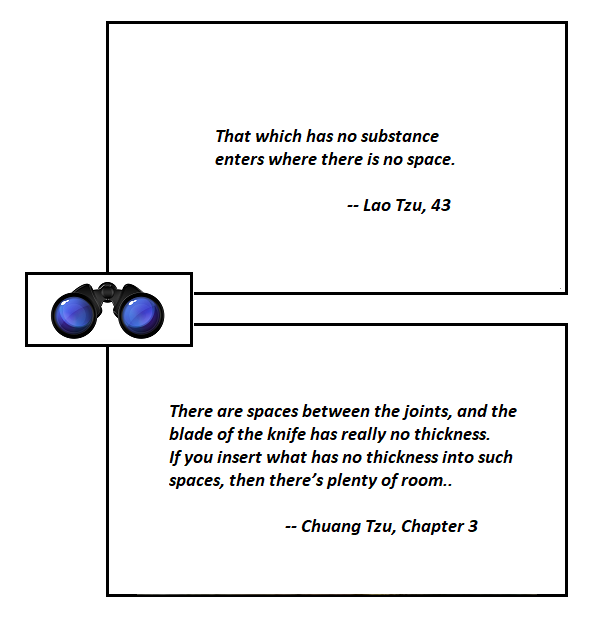

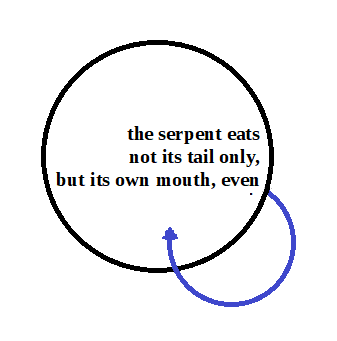

And over time, I discovered the obvious — that the fundamental game move involved two concepts, with one bridging link between them. So that’s the fundamental way to learn to play the HipBone Games. Over time, I’ve come to rely more and more on this simplest of HipBone Games, the DoubleQuote:

— leaving the larger HipBone Gameboards — the 8-move Dart board on up to the 120-odd Said Symphony board, dedicated to, you may have guessed it, Edward Said, and available for possible competition games and solo symphonies.

**

What’s a concept, you might ask — what constitutes a move?

I might use a different definition if I were taking about anything other than the Bead Game, but in this context, a concept is a rich idea — an idea with rich possibilities for association. Let me take a paragraph from a New Yorker piece as an example:

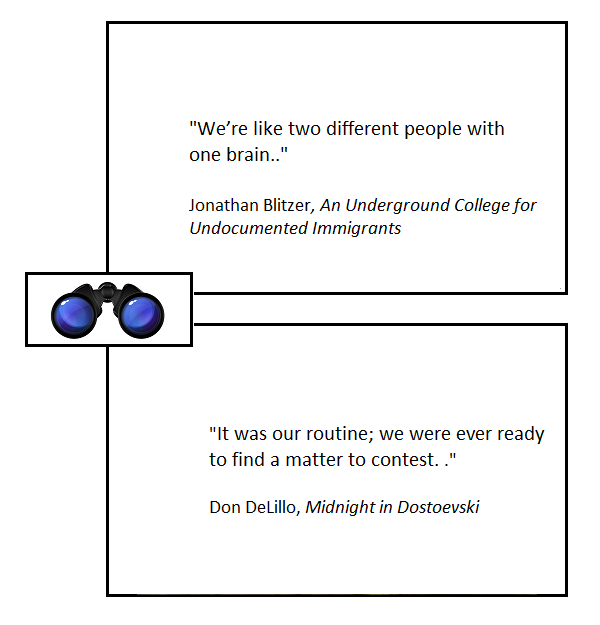

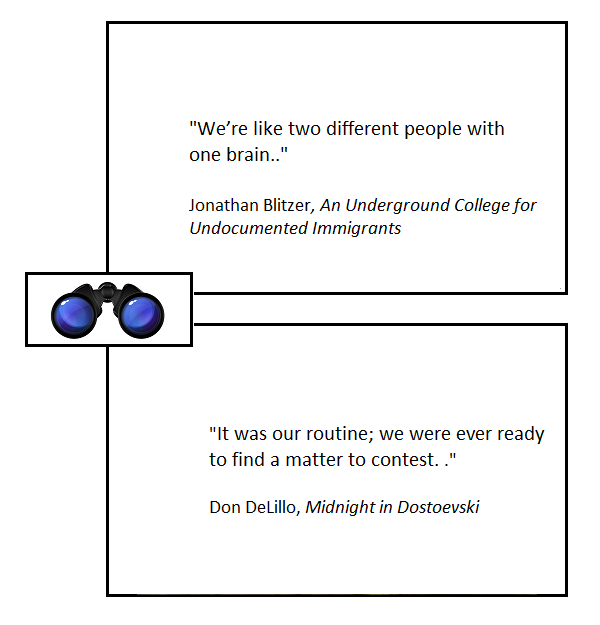

Melissa and Ashley, identical twins from Georgia, shared a bedroom while growing up. They had the same best friend, took classes together in high school, and dreamed of becoming artists in their own collective. “We’re like two different people with one brain,” Melissa liked to say.

The article in question is titled An Underground College for Undocumented Immigrants — so there’s room associations with the underground railroad perhaps, another situation where the official system repressed a minority, and that minority found ways to circumvent the system.

I’ve chosen this example, in fact, because it offers numerous associative possibilities — to other ideas, narratives, or statistical finds about twins, to other New Yorker articles, to underground movie theaters or catacombs, to those who dream of becoming artists — and in particular for my purposes here, because it’s about two people who think, almost as if they are one.

In fact, to emphasis this notion of unity and harmony, I might simply chose this statement for the first position in my DoubleQuote::

We’re like two different people with one brain

**

Let’s use a musical analogy, and say the two of them think in close harmony, or, since there are two of them, that thinking together, they constitute a duet..

The opposite of harmony,in which many notes played simultaneously form a chord, is counterpoint, in which differing melodic lines move between discord and resolution — harmony a “vertical” matter, synchronic, while counterpoint is “horizontal” and diachronic —

— and the opposite of a duet is a duel.

**

The two friends in Don DeLillo’s New Yorker piece, Midnight in Dostoevsky like to keep their minds at opposite poles from each other. As one of the two reports:

He liked to test himself on what he knew. He liked to stop walking to emphasize a point as I walked on. This was my counterpoint, to let him stand there talking to a tree. The shallower our arguments, the more intense we became.

I wanted to keep this one going, to stay in control, to press him hard. Did it matter what I said?

The actual phrase I’d place in juxtaposition to the first paragraph above might come from a discussion of whether the old man walking in front of them that day was wearing an anorak or a parka —

It was our routine; we were ever ready to find a matter to contest.

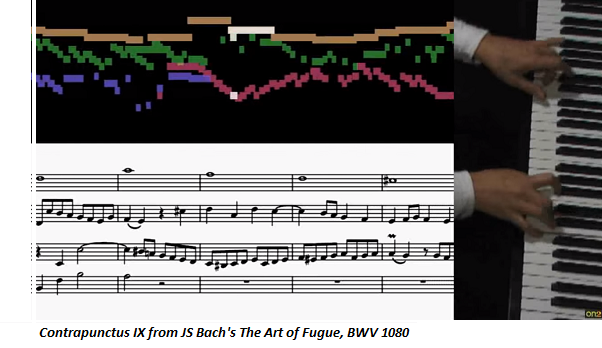

Again, the context — the article itself — is rich in associative potentials, with parkas, anoraks, Inuits, linguistics, life in the arctic circle, the whole idea of North — on which the pianist Glenn Gould wrote an entire radio opera —

— and note that Gould is himself a master of counterpoint, specializing in the work of JS Bach, and called his radio opera technique “contrapuntal radio” —

So:

“This was counterpoint” — the opposite of harmony, and full of both conflict and resolution, with phrases isolated and overlapping, paused and repeated, denial and occasional agreement and renewed denial — a duel, not by any means a duet.

And yet each of our two excerpts describes the conversations of two close friends, the one emphasizing unity, the other diversity. And it is in the similarities and differences between the two conversation — between duel and duet — that the two concepts link to become a single move.

**

Having given that extended example, let me present a few more DoubleQuotes, in their positions on the board — with minimal explanations:

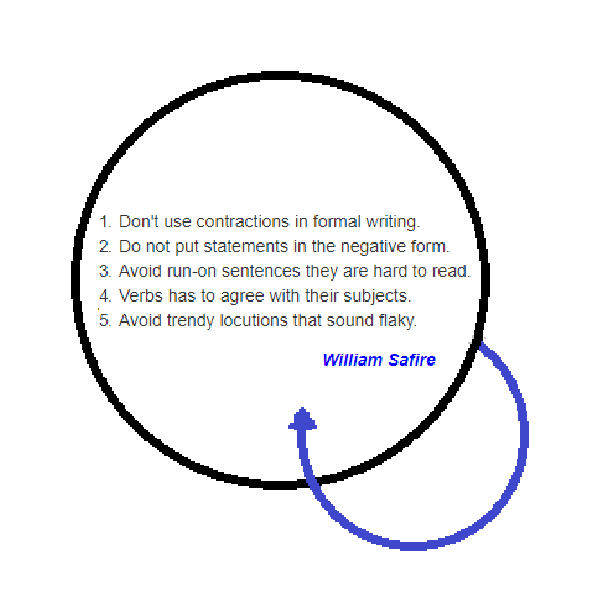

Some of them are made of names or phrases so simple, they fit on a mini-version of the board:

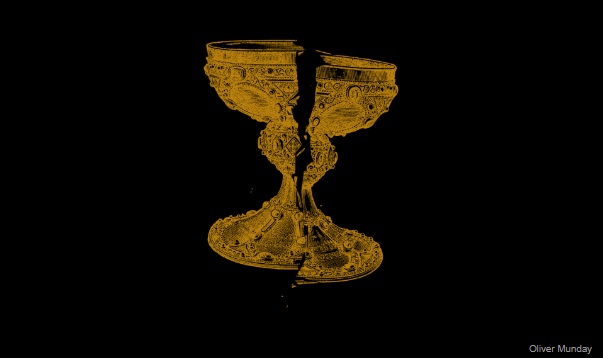

Some bring Shakespeare to bear on current events — in this case, Saudi Crown Prince MBS and the Khashoggi murder:

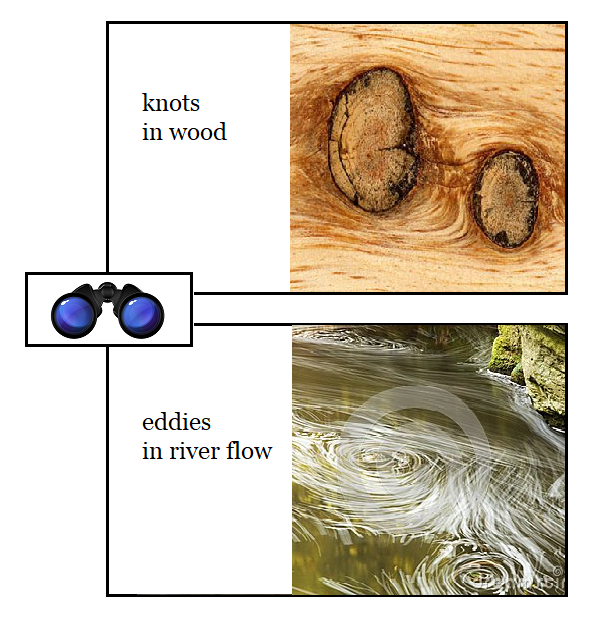

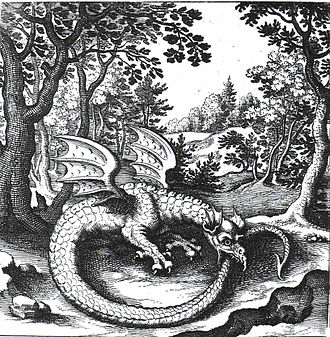

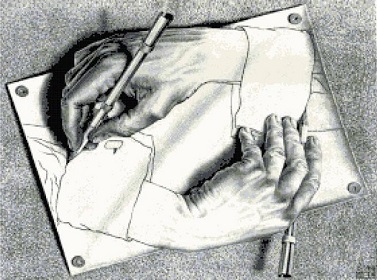

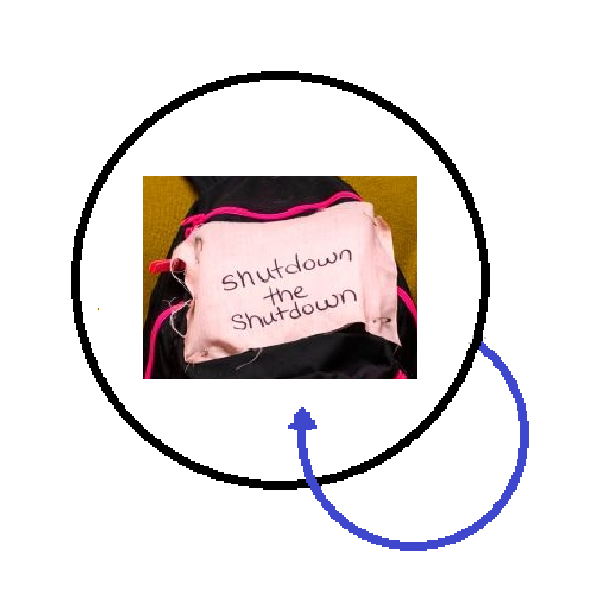

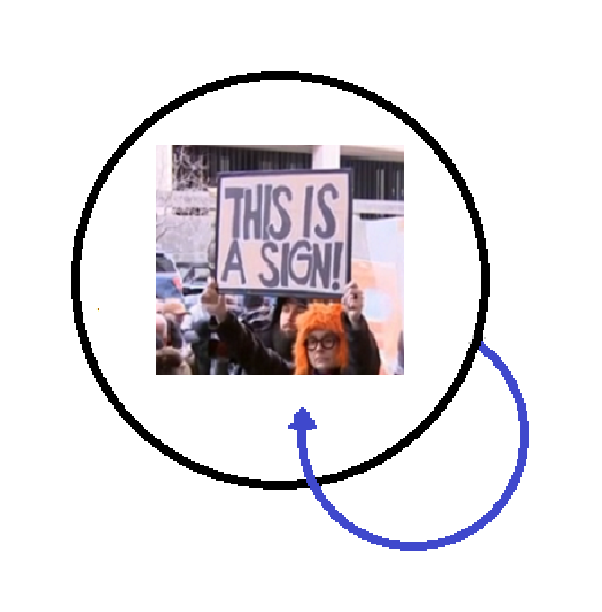

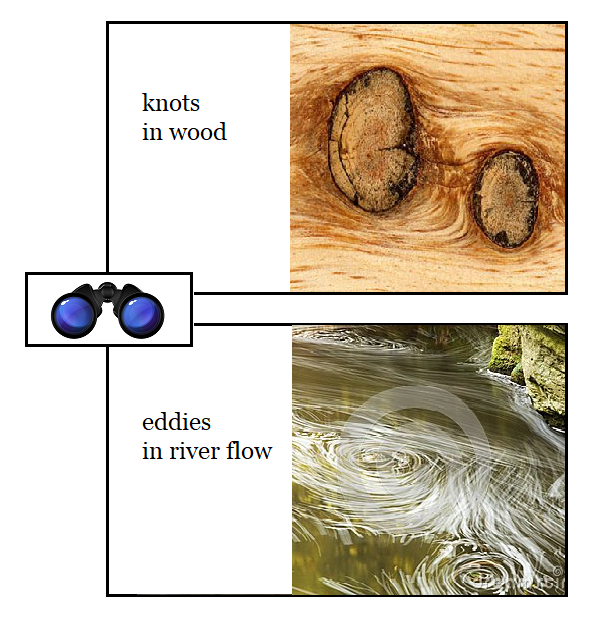

Some showing similarities in different materials:

Some making historical comparisons — this one’s in an earlier version of the same board —

or opposite opinions and creative practices of two of the world’s most distinguished physicists:

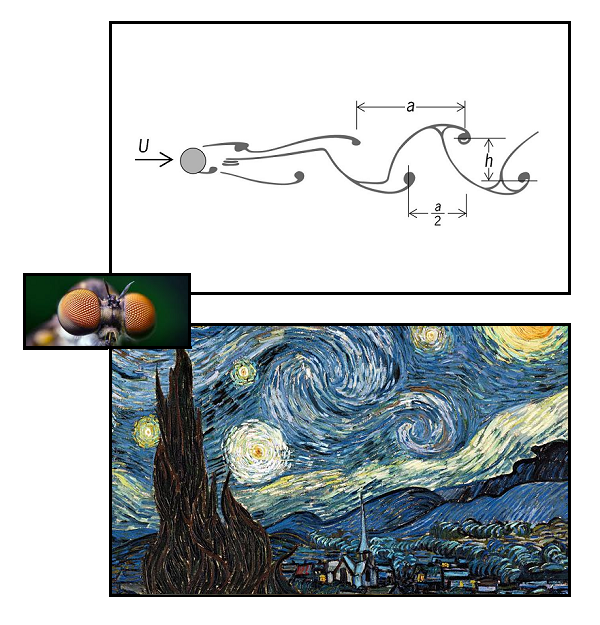

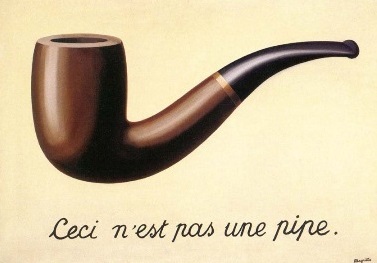

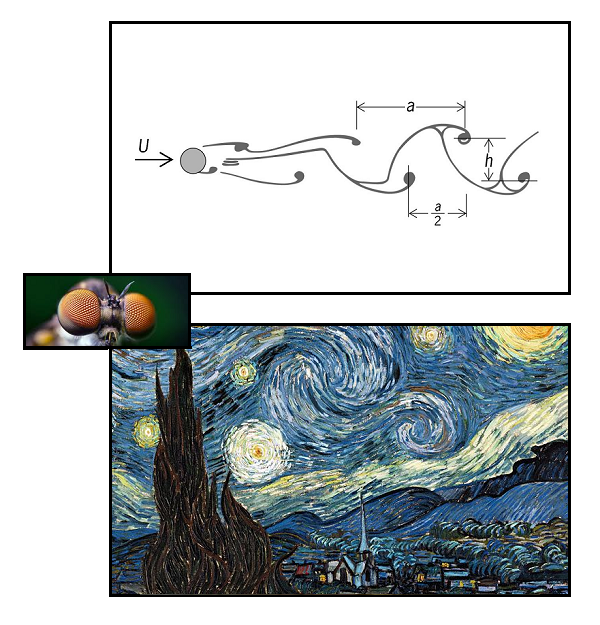

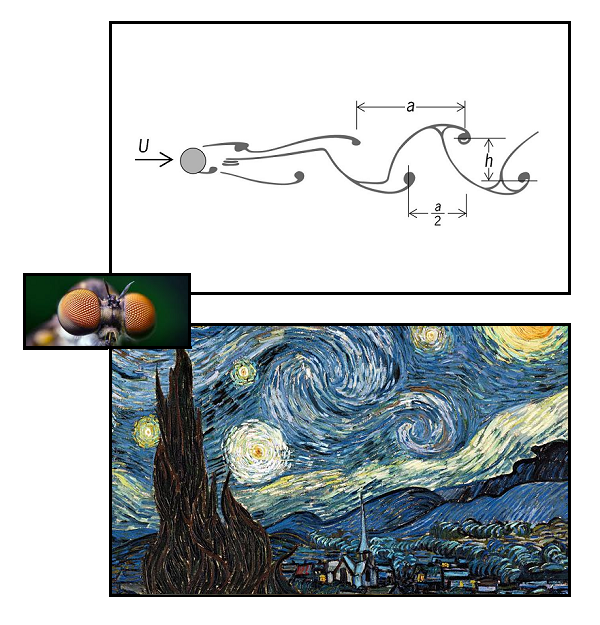

or — and this is my personal favorite, crossing as it does the great disciplinary boundary — between CP Snow’s Two Cultures — between art and science:

**

But either I’ve been very unclear, or you get the idea.

Here’s the blank DoubleQuotes board again, for you to download and drop your own examples into.

At gmail I’m hipbonegamer — feel free to send me your own, with any explanation you feel like making, and in a later post I’ll put them up here.