countries have had good growth but little poverty reduction. Bangladesh….had disproportionate poverty

reduction for its amount of growth.

The data is well known but the mysteries remain. A comprehensive look-in by master-class blogger and economist Jyoti Rahman. JR asks some important questions and sets up an impressive research agenda that is sure to benefit the laggards in South Asia – India (minus south), Pakistan, and Nepal.

JR has a story which sounds plausible but needs more data/analysis: Well, how about a stylised, and very speculative, story along this

line — while RMG has meant women entering the formal workforce, migrant

worker boom has sent a lot of risk-taking men overseas; aided by the

NGOs and microcredit, households have smoothed consumption and invested

in human capital of their children; but they have not invested in

physical capital, avoided entrepreneurial activities, and have not

pushed for a more investment-friendly polity.

……..

The Bangladesh Paradox:

The belief that growth brings development with it—the

“Washington consensus”—is often criticized on the basis that some

countries have had good growth but little poverty reduction. Bangladesh

embodies the inverse of that: it has had disproportionate poverty

reduction for its amount of growth.

That quote is from a November 2012 Economist article.

That article, and accompanying editorial, had a go at explaining the paradox. Joseph Allchin had a crack more recently at the NY Times.

The suspects are usual: garments, remittance, NGOs.

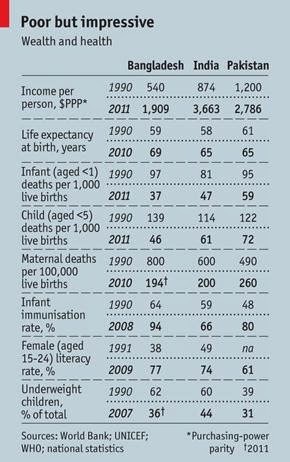

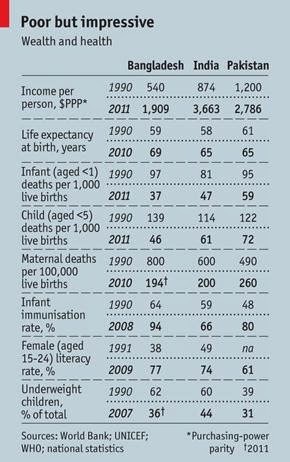

The first thing to explore is whether Bangladesh is compared with an

appropriate benchmark? Is it that Bangladesh has done better with its

growth and income, or is it India (or Pakistan) that is the exception?

The Economist notes that Bangladesh has a few features that India or Pakistan lacks:

Because of its poverty, it has long been a recipient

of vast amounts of aid. With around 150m people crammed into a silted

delta frequently swept by cyclones and devastating floods, it is the

most densely populated country on Earth outside city states. Hardly any

part is isolated by distance, tradition or ethnicity, making it easier

for anti-poverty programmes to reach everyone. Unusually, it has a

culture that is distinct from its religion: although most Bangladeshis

are Muslims, their culture and language are shared with the non-Muslim

Indian state of West Bengal. Religious opposition to social change has

been mild.

Has Bangladesh received more aid per capita than other poor

countries? How does Bangladesh’s growth-development trajectory compare

with other densely populated monsoon deltas — say, countries along the

Mekong? Or perhaps, Bangladesh should not be compared with India and

Pakistan as a whole, but with the four Pakistani provinces and 32 Indian

states?

Does a paradox remain if the comparators change? Does Bangladesh

still perform better in terms of development / living standard given its

growth / level of income? A proper research agenda would answer these

questions first.

Suppose the answer is yes, that the Paradox still remains, its resolution will rest on a two-part investigation.

The first part would explore the GDP story in detail. That Bangladesh

does better given its GDP does not make GDP irrelevant. Quite the

contrary. Bangladesh was wretchedly poor place until the 1980s. It’s not

a coincidence that things started getting better as the economy started

accelerating. We would want to know what about the GDP growth process

that may have contributed to the development in a relatively favourable

manner.

What do we know about the growth story of the past few decades?

From a strictly growth accounting perspective, we know that while

favourable demographic transition and female workforce participation

have helped, it is multifactor productivity that explains the GDP

acceleration. From a sectoral perspective, we know that agriculture’s

share of the economy has shrunk, that of manufacturing has risen, and

services have become more productive. And we know the particular

industry that has led the charge — readymade garments.

So far, this seems like a straightforward export-led manufacturing

driven growth story a la our neighbours to the east and north.

Yet, it’s not so clear cut when we look at the expenditure side of

GDP. Unlike the Asian fast industrialisers, Bangladesh has not

experienced an investment boom. In fact, low private investment relative

to GDP may be the single most important problem facing the country’s economy.

Of course, why investment hasn’t grown is a question that needs

further exploration — and the answers will have obvious policy

implications. But is there something to the consumption pattern as well?

Particularly, have remittance and microcredit affected consumption

above and beyond what would be implied by wages growth coming from

industrialisation?

In addition to the macro trend, do industrialisation, remittance and

microcredit interact in a way that have microeconomic — that is,

household and firm level — impact favouring consumption over investment

even after accounting for various market and government failures that

inhibit investment?

What am I getting at here?

Well, how about a stylised, and very speculative, story along this

line — while RMG has meant women entering the formal workforce, migrant

worker boom has sent a lot of risk-taking men overseas; aided by the

NGOs and microcredit, households have smoothed consumption and invested

in human capital of their children; but they have not invested in

physical capital, avoided entrepreneurial activities, and have not

pushed for a more investment-friendly polity.

We would want to explore this story further. We would also want to

explore the income side of GDP, and tie it into a political economy

analysis.

The remittance boom, for example, should see the labour share of the

economy rise. Of course, the question is, what happens to the money that

is remitted back? It’s reasonable to assume that unskilled labourers

are from the poorer parts of the society. So, in the first instance, any

remittance back to the villages is a good thing in that it reduces the

direst type of poverty — that is it stops things like famine or

malnutrition. But what happens after that? My tentative hunch is that a

lot of remittance has been saved but not invested in a productive way,

rather they ended up fuelling land/stock prices —this is an area that

needs to be explored in detail.

What about the RMG boom?

Theoretically, proceeds of the manufacturing boom should accrue to

both labour and capital. Has that happened? Has the process of

distribution been dynamic or static? Here, by dynamic I mean whether the

industries are going up the value chain —from the cheapest tee-shirts

to more expensive designer brands to leather and other fancier fashion

items to toys to cheap electronics to expensive electronics to stuff

that requires more skilled labour. If the process has been dynamic, then

we should expect less tension between labour and capital, because both

wages and profits rise over time.

In addition to the detailed exploration of the growth process, the

research agenda will need to focus on the factors that explain the

development above and beyond what might be expected from the growth

itself.

As a starting point, let’s take the four factors listed by the

Economist: government spending and policies on social programmes that

assisted family planning and empowered women; the green revolution;

remittance; and NGOs.

Let’s think about these factors in a systematic way.

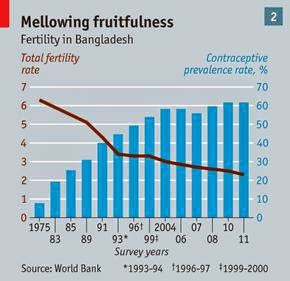

The chart on the left from the Economist illustrates the

female empowering social transformation. But how important has the

government, and NGO, interventions been relative to the advent of the

RMG sector. As far as girls’ education is concerned, Mushfiq Mobarak of

Yale finds the garments made the difference (this

is a subject of a detailed post). We would like to see the relative

impacts of industrialisation, direct government policies, and NGO

activities analysed across various metrics.

The green revolution is a relatively straight forward story, as is its impact,

and remittance we have discussed above. In addition, we would want to

know how, if at all, the impact of these factors have changed (and is

likely to change) in a more rapidly urbanising Bangladesh.

Finally, we would want to analyse the economics and political economy

of the NGOs —what the Economist calls the ‘magic ingredient’.

Large NGOs such as BRAC are as much business conglomerates as philanthropies. In fact, the Economist compared BRAC to Korean chaebols.

Is that a reasonable comparison? Do we understand the microeconomics of

NGOs? Does our view of Bangladesh Paradox change at all if we viewed

these NGOs as little different from Korean or Japanese business houses

at comparable stages of development? And what about the impact of the

NGOs on public finance, and indeed the state’s capacity to build

institutions in general?

Needless to say, this is a pretty ambitious research agenda. But it’s

hardly impossible. Is there anyone out there to tackle this?

…..

Link: http://jrahman.wordpress.com/2013/12/02/decoding-the-bangladesh-paradox-a-research-agenda/

……

regards

Bangladesh’s economy isn’t a disaster; but nothing to boast about:

PPP per capita Indian GDP = $6,572

PPP per capita Bangladeshi GDP = 3,581

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(PPP)_per_capita

Bangladesh is extremely dependent on foreign aid:

http://www.dhakatribune.com/tribune-supplements/2017/10/08/unused-foreign-aid-may-affect-countrys-economic-growth/

By contrast India receives almost no foreign aid as a percentage of GDP.

There are many reasons for Bangladesh’s poor economic performance relative to West Bengal India. One of the largest in my opinion is rising Islamism in Bangladesh. Many Indians use to conduct business in Bangladesh and visit Bangladesh. Many of them have fled. Bangladesh use to have a lot of freedom, including freedom of speech in the 1980s, 1990s, and even as recently as fifteen years ago. Most of that is long gone. Bangladesh is increasingly unsafe for locals, tourists, investors and business operations. Most minority muslims and nonmuslims have either holed up in fear or fled the country. In country journalists, bloggers and political leaders no longer say what they think for fear of death. The few who do speak out have fled Bangladesh to live in India, North America, Australia, Europe or some other area where the police are willing to protect them.

The absence of any freedom of speech has greatly suppressed business investment, entrepreneurship, product development, process innovation; and is a large driver of poverty.

This terrible tragedy has happened in front of my and all of our eyes. And it is a shame that few seem to care. Unfortunately what starts in Bangladesh will not stay in Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s slide into Islamism will greatly hurt India, China, Nepal, Burma, Thailand, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Europe, America and the whole world.

What can the world do to help Bangladesh save herself?