blinked as if giving out a signal….Were there any

eyes focused upon us, wondering why we were standing so close to the

river so late at night?…any soldiers wondering whether they will be able to take us down in

one shot?…….

……

….

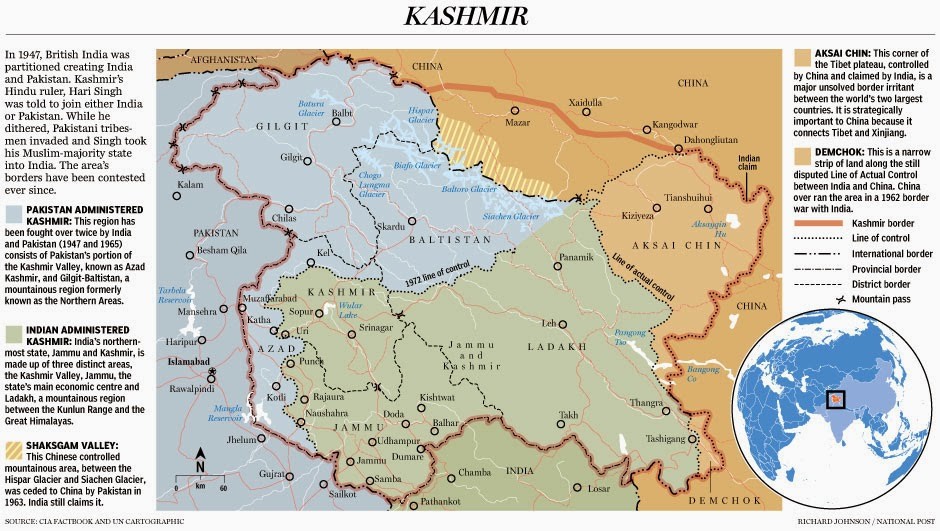

We have (mostly) unhappy feelings about the border wars on the Line of Control….the shootings, the torture, the be-headings. The (anti-Zionist, Jewish-American) Norman Finkelstein calls the mindset of liberal Jews who find themselves perched on the fence as: shooting…but crying. Well, we do not like being on the fence, and we do not want to shoot and we do not enjoy crying.

Thousands of civilians, militants and military people on both sides of the Line of Control (LoC) have died , some who are true believers, some who are only too happy to do their job and leave in time (and not in a casket), and the rest who live here and have no place to go…and are being driven slowly insane by the prolonged conflict (see below). And not to forget the shadow of the Bomb….there is no other border in the world which is as dangerous and deadly…..and also none as beautiful.

…….

….

We visited Kashmir when we were very young, but we will never visit the place again. There is no doubt that India (and Indians) are an oppressive force in the valley (on the lines of Gaza, Chechnya, Xinjiang…). When you feel hurt hearing the slogan: “Bhooka Nanga Hindustan, Jan Se Pyara Pakistan”…please reflect on what YOU would do if you lived in an occupied zone.

Of course Kashmiris are guilty of some unforgivable sins as well. If you are a Arundhati Roy fan, you may know that the India actually facilitated the expulsion/exile of the Pandits, in order to darken the (righteous) cause of Kashmiris.

……..

Following this theory, the fatwa issued daily from the mosque-speakers in 1989-1990: Hindus leave your homes, leave your women behind”……was actually Congress propaganda!!! And yes, the Pandits are also rotting away in refugee camps and are being driven slowly insane by the prolonged conflict. And, no, they will never see their native land again.

The Yazidis (called devil worshippers by the Iraqi islamists) are facing the same situation right now (propaganda by Zionist lobby??) – history repeating itself as tragedy.

…..

Between 80 and 100 men are believed to have been killed. Scores of women and girls were taken away in trucks, possibly to be sold off as slave-wives to IS fighters.

…….

Is there some sort of global karmic equation that permits people to be oppressed and carry out oppression in equal measure? Shall we all die for our promised land and promised causes (we will all die anyway)?

In the sub-continent it would be nice enough if the bellicosity (on both sides) was toned down a bit. But then we realize that are only 960 years of fighting left (see quotation below) and it will be (approx) thirty generations going forward for peace to take hold (hopefully).

…………..

…..”So please, Mr. President and members of the Security Council, realize

the implications. The Pakistani nation is a brave nation. One of the

greatest British generals said that the best infantry fighters in the

world are the Pakistanis……We will fight…… We will fight for a thousand

years, if it comes to that“……

………………………………

My wife and I stood under a starry night. We were here to celebrate our

first wedding anniversary. The breeze that the river brought with it

through the gorges was chilling. Beaten by the strong sun during the day

we couldn’t have imagined that the night would be so cold. The river

flew at our feet, its fast-paced torrents crashing against the rocks on

the riverbed.

The sound echoed through the valley. A dark

mountain stood in front of us. Earlier in the day, we had sat here

sitting under a tree, sipping our tea and marvelling at the beauty in

front of us. It was a gorgeous mountain, with flat notches cut into its

side to create fields for agriculture. A few wooden houses stood around

the plains and some villagers were working on the fields.

Then

there wasn’t a single light. From the top of the mountain a light

blinked every once in a while as if giving out a signal. Were there any

eyes focused upon us, wondering why we were standing so close to the

river so late in the night? Were there any soldiers eyeing us through

their scopes and wondering whether they will be able to take us down in

one shot?

For years, there has been peace here and no bullet has

crossed the river from either side but that does not mean that paranoia

doesn’t exist. They still look at us with suspicion and we do the same

to them. A few years ago we would have been shot for standing so close

to the Line of Control, we had been told.

The Mujahidin once used to cross from here.

I

tried imagining a trip into the Indian part of Kashmir. The first step

would be to cross this freezing water flowing with vengeance. The next

step would be to navigate through the jungles of Kashmir in the darkness

of the night, worried about the wild animals that live here and focused

on avoiding the Indian soldiers who patrolled these forests. Once

someone is caught, then start the tales of torture.

“Look at that

mountain,” said Awais, our host at a small guesthouse. It was a bright

day. Behind the mountain I could see the depth of a clear blue sky and a

few clouds. I tried following the direction of Awais’ finger carefully

and noticed the silhouette of a wire fence. Next to it there was a

wooden platform for the sentry.

“Is that India?” I asked my host.

“No. That’s Indian-occupied territory,” he replied. “That fence has

been raised by the Indian army in the past few years and a lot of hue

and cry was raised by the Pakistani government.”

“Is this where the Mujahidin used to cross over to Indian-occupied Kashmir?” I asked.

“Yes.

But they don’t any more. Ever since Musharraf made a deal with the

Indians, we have stopped sending Mujahidin from here. Earlier, they used

to cross the LoC from here and also Sharda, which is about two hours

north from here. This is why the Indian soldiers used to shoot here. You

and I would not have been able to sit here.

Things were so bad that in

the night if someone as much as lit a cigarette he would be shot. This

road that brought you here from Muzaffarabad could not have been used.

In retaliation, of course, our Pakistani soldiers also used to fire.

This condition continued for a decade or so, from the early 1990s to

early 2000s. In those years about 3,000 people died from this region.

About 200 Mujahidin used to cross every night.”

“Did the Mujahidin also have their training camps here at Karen?”

“Yes.

But not any more. Now they only operate from Muzaffarabad and cross

over from Rawal Kot region [which is south of Muzaffarabad, while Karen

and Sharda are north of it]. Cross-LoC firing takes place in that region

only now.

But you know there is a much bigger war coming and you should

brace yourself for that. That would be a war over water. The Indians

have constructed Kishenganga on this river on their side and soon there

would be water shortage in Pakistan.” The Neelum River, which acts as the LoC in this part of the Neelum valley, is known as Kishenganga on the Indian side.

Later,

a mosque from across the river sounded the azaan, identifying the time

for prayer. No azaan followed from the Pakistani side but a few men and

women sitting around me decided to go and say their prayers. This was

once one village, Karen, now divided between two countries. Most of the

houses on the Indian side of the village are vacant.

The

inhabitants were made to leave during the time of insurgency, when

Mujahidin used to cross over from here. Most of these empty houses have

been taken over by Indian forces. The locals on the Pakistani side tell

me there are many Kashmiris from the Indian side of Karen who have now

come here too.

“Every Sunday, divided families gather on both

sides of the river and wave each other,” said Awais. I glanced at the

river and realise that given its width and noise, it would be impossible

to talk. Waving is all one could do. “During the winters, the river is

one-fourth of what it is right now. At that time, one can easily talk to

the person on the other side. There are many divided families here at

Karen. A mother would be here while the daughter would be there. So many

families.”

A poster next

to the army checkpoint depicted a picture of a young child with a leg

missing. There were pictures of an aircraft missile and a landmine next

to it. “Beware of the moves of the enemy,” it stated. The poster

cautioned children not to play with unidentified objects and to inform

army officials in case anyone comes across any.

The younger

officer at the army checkpoint returned my identity card. “Are there a

lot of unused missiles and landmines in this region?” I asked him. “Yes,

of course,” he said. “The enemy is right across.” The army checkpoint

was hidden by a concrete wall. A board here said that it was prohibited

to photograph the checkpoint. The cautionary poster was located on one

of the walls of the checkpoint. I wasn’t sure if the rule applied to the

poster as well. I did not want to find out.

Since our departure

from Muzaffarabad, this had been the fifth time that I had been stopped

by an army checkpoint. At every stop they entered my information into a

register, asked me where I was coming from and where I was heading. This

historical village of Karen, established some time in the tenth

century, has become a tourist destination since the ceasefire in this

region. It is about 80 km from Muzaffarabad, a journey that takes about

four hours on the treacherous mountainous road.

A few kilometres

north of the city of Muzaffarabad, the river Jhelum turned further west,

while the Neelum tok it place. The fast-moving river is a continuous

companion to a traveller on this road. As one heads further away from

the capital of Azad Kashmir, or Pakistan-administered Kashmir, the LoC

gets closer. Soon this narrow river remains the only thing that

separates the two arch-rivals, both armed with nuclear weapons and one

of the largest standing armies of the world.

Sometimes Indian

Kashmir recedes from the river and sometimes it touches the bank of the

river. While travelling on this road, my wife and I constantly tried to

figure out whether the mountain and the houses on the other side of the

river were still Pakistani or had become Indian.

About an hour

before Karen comes Athmuqam. After passing a checkpoint I slowed down

the car to catch a glimpse of the Indian town on the other side of the

river. There was a huge cricket ground with the Indian flag hoisted on

one side. A wooden bridge connected the two settlements flanking the

river. This is the point where Kashmiris are allowed to pass over to the

other country’s territory to see relatives who have been stranded by

the LoC. This is also the point where, it is rumoured, one can purchase

smuggled Indian whiskey by bribing the soldiers.

The

name of this part of the Neelum valley has been changed to Vigilant

valley. There are army boards and posters throughout the road stating

that. Here too there used to be regular firing between the two armies.

Standing

on the top of the mountain, it is hard to tell which peak is occupied

by India and which belongs to Pakistan. The river flows, unaware of the

raging battles above it. It snakes through the valley dividing

mountains, communities, villages and families on both sides of the LoC.

Standing

next to us was a young mentally challenged man. He had been following

us up this mountain. There are many here throughout the Neelum valley.

My wife, who was training to be a therapist, had reason to believe that

their condition is linked to the firing that ravaged this valley for

years.

We stopped at a tea shop and sat in a garden. From here,

we could see the village and the river below us. On both the sides the

army was camouflaged behind trees. Only the villagers were left

uncovered.

Mohsin, the shop vendor, was born in 1988, a year

before the escalation of insurgency in Kashmir valley on the Indian

side. “There were hardly any local Kashmir Mujahidin being trained in

the camps,” he told me as he made tea for us. “There used to be a few

from the Indian side. Then there were Pathans, Punjabis, Chechnyians,

etc.” Everyone knew where these camps were.

But that did not mean

that sympathy for Kashmir’s liberation did not exist in Pakistani

Kashmir. They supported the insurgents. Sometimes, if the Mujahidin were

traveling with too many bags, the locals would help them cross the LoC.

That’s what Mohsin told me.

“There used to be regular firing

here from both the sides but that did not affect life here at the

village,” claimed Mohsin. “They never used to fire at the village. They

would only fire at army posts. If they wanted to attack the village

would they have left us stay here? Look at us. We are completely

exposed. As children, the firing used to be a sport for us.

“We

would hide in corners and see the armies firing at each other from

across the mountains. It was very exciting for us. This road that you

came by was not open for business but there were other roads that

connected us with Muzaffarabad and Pakistan. That road could only be

travelled on jeeps but the villagers used to travel regularly on them.”

“Would our soldiers fire on Indian villages across the LoC?” I asked him.“They can never do that. That is Pakistan as well. There are Muslims living there.”

“I was told that about 3,000 people died here due to cross LoC firing?”“That’s not true. At most only four to five people have died due to the firing. Here they like to count as shaheed even those who died after falling off a mountain.”

Once

again I took out my identity card and handed it over to an army sentry

standing at the entrance. “How far is the LoC from here?” “I don’t

know.”

“In what direction is the LoC from here?”“I don’t know.”

We

climbed the ancient set of stairs to reach the ancient university of

Sharda. A board here stated that this was once an ancient Buddhist

university. It is a lonely structure standing in the midst of a

protective wall. There is an army unit deposited under the university. I

was forbidden from taking any photographs of the army unit.

“The

mountain behind this mountain belongs to the Indians,” said our waiter

as we sat down next to the river after visiting the temple. “Here too

there used to be firing. The Indian soldiers used to fire into our

territory including our villages. We had no other option but to

retaliate.”

“Did we attack their villages?” I asked him.

“How could we? Those are, after all, our own villages.”

(Haroon Khalid is the author of A White Trail: A Journey into the Heart of Pakistan’s Religious Minorities; Westland, 2013)

….

Link (1): A-journey-along-the-Line-of-Control-in-Pakistan

Link (2): kurds-abandoned-the-yazidis-when-isis-attacked

Link (3): Bhuttos_farewell_speech_to_the_Security_Council

….

regards