negative given Washington’s friendliness toward the Egyptian

military and hostility toward Muslim Brotherhood….But in fact “no matter which side of the domestic dispute an

individual was on, he or she was likely to be opposed to the United

States”…..

Despite U.S. attempts to stay neutral in the

conflict, both military and Muslim Brotherhood supporters believed the

U.S. was working on behalf of the other side…..

….

How do modern Arabs (approx 4mil on Twitter out of a total population of 400 million) feel about America (and Americans)? A careful analysis of tweets tells us a lot- they really hate Iran (much more than Israel AND America) and much more.

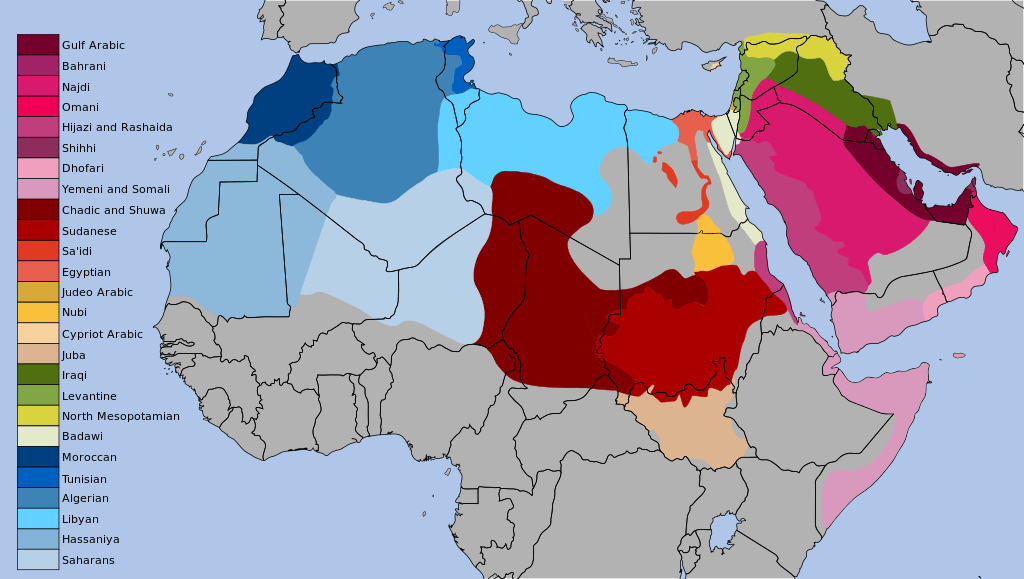

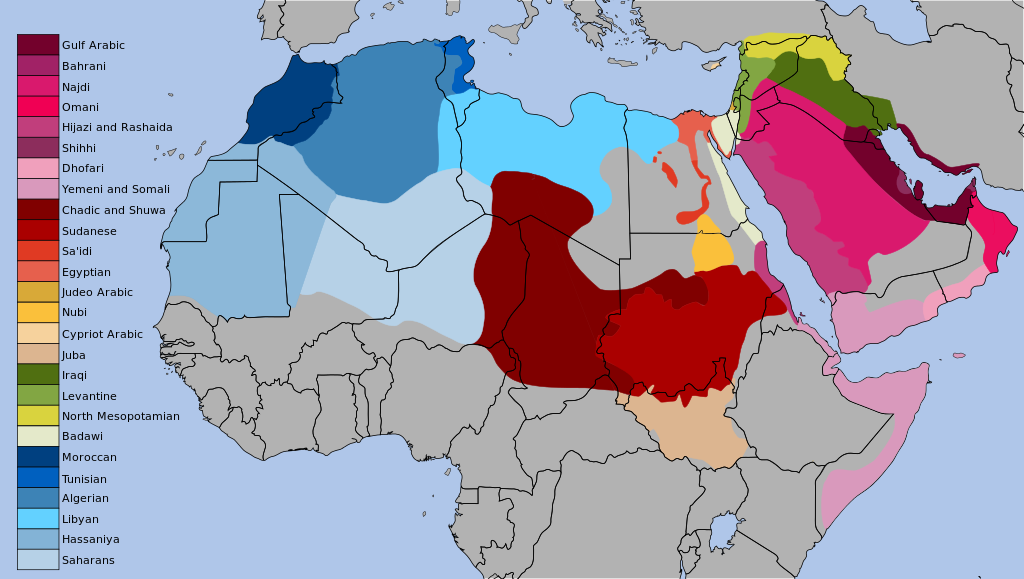

This leads us to a question that has always been a point of confusion for us: who are the Arabs and what are the major Arab communities? Just like India can be (imperfectly) divided by linguistic communities (and except for the South these communities are all loosely tied together through an ancestral Sanskrit bridge), we may get a better understanding of Arabic communities by observing the distribution of Arabic dialects [ref. Wiki-map below].

….

…..

Is anti-Americanism motivated by specific U.S. policies or a more

generalized antipathy to American culture? Do people who hate U.S.

foreign policy also hate Americans?

…

These are among the questions addressed in an innovative new study

of anti-American attitudes among Arab Twitter users, which was

presented at the American Political Science Association annual meeting

here in D.C. last week.

The short version of the working paper’s

conclusion is that Arabic Twitter is generally anti-American (though to a

lesser extent than it is anti-Iranian) but that these attitudes are

motivated more by specific events than general hostility to American

culture. Unfortunately, these attitudes seem to be present on multiple

sides of the region’s political divides.

The authors, political scientists Amaney Jamal and Robert Keohane of

Princeton and David Romney and Dustin Tingley of Harvard, worked with

the analytics company Crimson Hexagon to analyze the sentiment of Arabic

Twitter in 2012 and 2013.

….

Twitter users aren’t a perfect proxy for

public opinion—the population is likely weighted toward younger, more

educated people, and wealthier countries like Saudi Arabia and the

United Arab Emirates are overrepresented. The data, though, can give a

snapshot of what 3.7 million (the number of active users in Arab

countries) people are thinking and provide valuable information from a

number of countries that have restricted traditional public opinion

polling in the past.

Overall, the authors found that “the conversation on Twitter, in

Arabic, about the U.S. is especially negative towards U.S. policy; the

conversation about U.S. society is also mostly negative but much

smaller.” But that’s less interesting than how Arabic Twitter responded

to specific events.

The first test case is the 2013 overthrow of Egyptian President

Mohamed Morsi. Seventy-four percent of the tweets referencing the United

States around the time of Morsi’s fall were negative, and only 3

percent were positive. (The rest were neutral tweets noting some piece

of news.)

…

You might expect that supporters of the coup would be less

negative given Washington’s traditional friendliness toward the Egyptian

military and hostility toward Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood. But in fact,

the authors write, “no matter which side of the domestic dispute an

individual was on, he or she was likely to be opposed to the United

States.” This fits with what was observed in reporting from the time:

Despite U.S. attempts to stay (or at least appear) neutral in the

conflict, both military and Muslim Brotherhood supporters believed the

U.S. was working on behalf of the other side.

Next, they analyzed tweets about the conflict in Syria, particularly

following the chemical weapons attack in August 2013, when it appeared

likely the U.S. would launch a military intervention against Bashar

al-Assad’s government.

Again, there was little support for the United States—just about 2

percent of tweets, all of them from opponents of Assad. But while regime

supporters were more anti-American, “even for the anti-regime Tweeters

there were 250 percent more anti-U.S. tweets than pro-U.S. tweets before

the chemical weapons incident, and about 1,000 percent more after the

event.”

While on opposite sides of the Middle East’s bloodiest conflict in

decades, these Twitter users were fairly united in antipathy to the U.S.

But attitudes toward the U.S. are a bit more nuanced than you might think. Looking at the online response to the anti-Muhammad Innocence of Muslims video,

which prompted large and often violent demonstrations throughout the

Muslim world in the fall of 2012, the authors found that the majority of

Arabic tweets either urged followers to ignore the film or pushed for

individual action against it. Relatively few, however, could be

construed as “clear condemnation of American society in general.”

The authors write: “We did not find tweets with statements such as

‘This means that all Americans hate us’ or ‘All of American society and

people should be condemned.’ ”

They also looked at instances where Americans were the victims.

Following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, the largest number of

non-neutral tweets (20 percent) expressed the opinion that the attack

wasn’t a significant news event, followed by those expressing fears of a

backlash against Muslims in the U.S. Eight percent supported conspiracy

theories blaming the U.S. government for the attack.

Again, there’s evidence of anti-Americanism—only 5 percent of tweets

expressed sympathy for the victims—but in this case the authors didn’t

observe tweets celebrating the attack on U.S. society.

In the case of a non-political event, 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, there

were again a large number of users saying the storm wasn’t important.

Ten percent said the U.S. had it coming. But virtually the same number

of tweets rejected that view, and “25 percent of tweeters (almost

80,000) commented favorably on the U.S. government’s handling of the

disaster, often as a contrast to the incompetence of Arab governments.”

Overall, about a “third expressed views that can be interpreted as

generally favorable toward American society.”

If all this makes it seem as if Arab tweeters are knee-jerk

anti-Americans, you should see how they feel about Iranians. While

trailing the United States in total references, Iran got more mentions

on Arab Twitter than any other non-Arab country, ahead of Israel,

Turkey, and India.

…

The authors found political sentiment toward Iran to

be “overwhelmingly negative,” with so few positive tweets that the

proportion was impossible to estimate. While attitudes toward America

itself, rather than American policy, often seem more ambivalent than

negative, views of Iran are starker. “In both the polling data and even

more in our Twitter data, one observes admiration for American popular

culture, helping to create such ambivalence. There is no such Arab

admiration for Iranian popular culture, and no discernible ambivalence,”

they write.

In terms of efforts to improve America’s image in the Arab world, the

paper contains both good and bad news. Arab Twitter users’ antipathy

toward America itself, or Americans, doesn’t appear to be exceptionally

hostile. But suspicion and opposition to U.S. foreign policy appear to

be so deep and so widely shared, even by those on opposite sides of

other contentious issues, that it’s hard to imagine how the U.S. could

begin to rebuild trust.

There may be a lesson here for the Obama administration’s foreign

policy. For understandable and sometimes admirable reasons, the

administration has often tried to avoid being identified with one side

or another in domestic disputes in the Arab world. The U.S. admonished

the Egyptian military’s crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, but eventually normalized relations. It provided aid to some of the rebels fighting Assad, but not enough to really turn the tide of the civil war.

…

Obama’s intention here may have been to combat the perception that

the U.S. meddles in the internal affairs of smaller states. But in some

cases, by refusing to take a side, the American government may have

deepened the suspicion that nobody should trust the United States.

….

Link: slate.com/whatever_america_does_arabic_twitter_will_hate_it.html

…..

regards