This post is contributed by याज्ञवल्क्य, also known as @Saiarav Sai (@Saiarav) / X (twitter.com) from X.

The God lording over the oil market has almost always turned a benign eye towards Modi. Oil prices fell by nearly half within a year of him becoming the PM and has stayed moderate for most part of his rule, a big blessing for a a country which depends on imports for more than four-fifth of its consumption. And Modi has used this divine largesse really well, taxing it heavily and testing the limits of his political capital and used these revenues to fund his ambitious capex program amidst anemic overall tax collections. How the timing of oil price movements has been near perfect politically for him can be a separate post in itself; but I will just note that if you had asked an oil analyst in March 2022 where oil prices would be at the start of 2024 if A) the Russia-Ukraine war continued to drag on and B) the developed world saw a period of double digit inflation — his/her answer would likely have been a triple digit figure. But yet here we are, at the start of 2024, with Brent trading under $80.

Petrol and diesel prices stay high despite lower oil prices

So here we are, with oil under $80 and yet the Modi sarkar has not deemed it fit pass on the munificence to the hapless consumers who still have to cough up nearly Rs.100/litre for petrol and diesel, the same level it was in early 2022 when oil had crossed $100/bbl. You might be wondering why I have started with a rambling introduction to get to this point — and I have no reason to offer, except perhaps that I am abusing the munificence offered by Medium, liberated from the character limit from my standard social media app. Thanks for indulging me, dear reader, now I will get down to business, I promise. (Not a good thing to abuse munificence of any kind, which is kinda the point of this post).

A lot of noise, too little light in the debate on fuel pricing

While this issue periodically generates heated debates on X, for the most part, it has been largely ignorant chatter and largely driven by one’s political leanings. And I have not come across any piece in mainstream media which has attempted to shed light on this issue. And that is both astonishing and extremely sad — here is the question regarding pricing of the most important commodity for any economy, and people do not know how it is priced? And we are talking of third largest oil consuming economy in the world here. It is astonishing because oil and its products constitute one of the most transparent, liquid and well understood markets amongst all commodity markets.

So here is my modest attempt to shed a tiny bit of light.

In India, the oil marketing business is largely dominated by oil PSUs who also have a refining business. The business model for oil refining and marketing is pretty straightforward:

A) OMC purchases oil, most of it is imported. The price of oil is linked to Brent, the global oil benchmark. So the refiner pays Brent oil price + ocean freight + insurance. (I am keeping it simple here — the actual price can be a bit higher or lower than Brent)

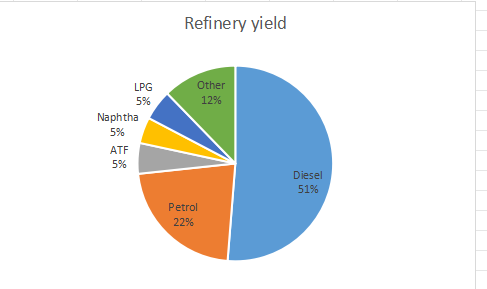

B) The OMC refines the crude oil in its refineries resulting in various petroleum products — primarily three high value products diesel, petrol and ATF but also propane, naptha etc. The chart below shows the yield of BPCL refineries in 2022–23 — the three high value products account fot nearly 80% of the total output.

C) The products are sold to end customers. For petrol and diesel, which is what this discussion is about, this would mean transporting the products to petrol pumps. Further, the marketed volumes for an OMC could be higher than its refining capacity, which means it will have to buy some part of its products from private refiners (Reliance and Nayara).

The OMCs provide value-add at two stages — refining the oil and marketing the oil and expect to be rewarded for the same. Let us take an example of how that works. First, at the refining stage, the company makes a margin which is the difference between weighted average selling price of all the refined products less the crude landed cost — this is called Gross Refining Margin or GRM. High value products (petrol, diesel and ATF) sell at a price well above the crude oil price while a product like Naphtha sells for less than the crude price. But keep in mind, the high value products account for 80% of volume and hence driven the GRM. As the term implies, this is just the ‘gross’ margin and the company obviously has operational expenses during the refining process.

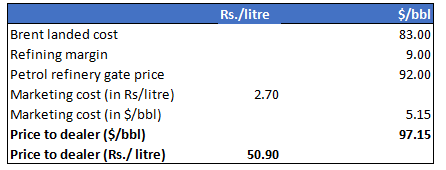

At the marketing stage, the company would expect a margin for maintaining a retail network and transporting the products to the dealers. And of course, there are costs of marketing the products as well. As of 2019, the per litre marketing cost + margin was Rs. 2.0–2.5 per litre (source: page 60 of this Petroleum ministry report). So let us say, its Rs. 2.7 currently accounting for inflation. The unit of measurement will keep shifting from barrels to litres, so you might want to keep in mind that 1 barrel = 159 litres.

Continuing from the above table, let us say, the OMC sells petrol at the refinery gate at a price of $92 (which would be refining margin of $9/bbl). Adding in a marketing cost of $5, the price to the dealer would ultimately come to Rs. 50.9/litre.

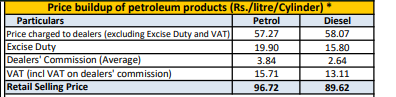

Adding to the price paid by the dealer, we then have the central and state government taxes and the dealer margin. Currently the price build-up for petrol and diesel (for Delhi) stands as follows:

Source: PPAC November 2023 report

Note that the price at which it is sold to the dealer is Rs.57–58 which implies a per barrel price of $109–110 while Brent currently trades at <$80. Since the marketing cost & margin is fixed, that means, the OMCs are getting a refining margin of $20+/bbl on both petrol and diesel.

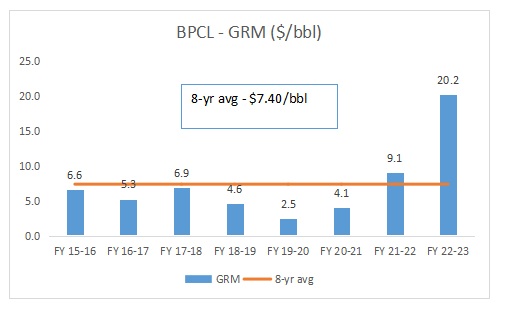

Is $20 high, or is it low, or is it normal? Below is the chart of BCPL’s GRM for the last 8 years. Note that this is the GRM for its entire set of product and petrol and diesel margins will be a couple of $ higher.

Typically, OMC GRMs have averaged mid single digits and the last two years, and especially FY 22–23 were outliers.

But what is the official pricing policy?

In theory, petrol and diesel prices are deregulated which means prices track the global prices for the two products (which is simply Brent price + regional refining margins). But it does not take an oil market expert to figure out that the policy has been quietly buried since early 2022.

The pricing is arrived at by what is called the Trade Parity Price (TPP) which is the weighted average of Import Parity Price (IPP) and Export parity Price (EPP) weighted in the 80:20 ratio. IPP simply means what is the theoretical price at which petrol or diesel can be imported to India ( we do not need to import since we have surplus refining capacity) — that price is basically the one at which refiners in our region will find it attractive to export to us. In other words, IPP for petrol and diesel is based on the refining margin of the two products in our region. The same concept applies for EPP — it is the price at which one can export which is linked to refining margins in the key export markets. Typically, the margins in Singapore market is used as the benchmark. And that explains why refining margins shot up in the last couple of years.

Underrecovery ….or how OMCs made bountiful GRMs but little money in FY 22–23

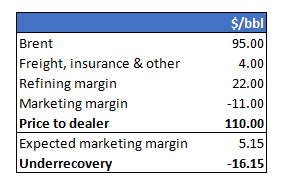

A $20/bbl GRM in FY 22–23 should have been a major cause of celebration for OMCs but it was not for the simple reason that the GRM was a notional number. For all of FY 22–23, the OMCs were selling petrol and diesel at Rs.57–58/litre to the dealers which is roughly around $110/bbl. Now considering Brent averaged $95 during the year and shipping costs had shot up during the year, this is how BPCL’s overall margins would have looked for petrol assuming a $22/bbl margin. Remember that the company is supposed to make $5.15/bbl towards marketing margin and costs. Instead, they incurred a loss of $11/bbl. And that is what OMCs, quite morosely, term as underrecovery. In reality though, the company did make a combined refining & marketing margin of $11/bbl but if one assumes refining and marketing costs of, say $8–9/bbl, they made very little in terms of cash profits from sale of petrol. There is also the further angle that they would have had to purchase some portion of petrol and diesel from Reliance and Nayara at global prices (ie $95+$4+$22 = $122) and sell that for $110. And on top of that, they had to incur huge losses on LPG cylinder sales, so yea overall a tough year, but I digress. The case that BPCL will be putting forth to the government is that they made $16/bbl underrecovery on petrol and diesel in FY 22–23 and they should be allowed to recoup those “losses” — my rough estimate is that that amounts to Rs.25,000 crores to be recouped!! To put this number in perspective, BPCL annual profits have averaged 8–12K crores in the past and the company is asking that they be allowed to make 25–30K crores for FY 22–23 because, hey, GRMs were so high.

So what is a reasonable GRM for OMCs?

Singapore refining margins for petrol and diesel are currently around $10 and $20 respectively. So if one goes by that figure, diesel should be around Rs.55 to the dealer might well be justified while petrol price should be around Rs.51. As a reminder, the current price to the dealer is Rs.57–58.

So even based on market pricing, there would be a case for cutting the petrol price. Of course, the question that arises is what about the losses incurred in FY 22–23, which I will come to later. But I would argue that the government has anyway jettisoned their pricing policy and should therefore stick to that changed stance and just view it as what is a reasonable GRM that the OMCs should be getting. I would say, $6.5/bbl is a pretty healthy margin. Or stick to the current pricing policy and slap a windfall tax (just like they do on exports of refined products).

One counterargument to this is that OMCs have ambitious growth plans and these high GRMs will be really helpful. In my view, they should just be asked to borrow money.

In the next section, I discuss what the potential for cutting prices is.

If we go strictly by the official fuel pricing policy, then BPCL needs to be allowed to recoup its underrecoveries of Rs.25K crores, so any cut is out of question, for this year, or the next, or maybe even the one that follows — and that is asuming oil does stay at $80. Or Modi could request BPCL to be let bygones be bygones — and I am sure the BPCL CEO, as a good corporate citizen, will give it a sympathetic hearing — and ask them to adjust the price down to current TPP levels, in which case, as I have pointed out earlier, there is scope to cut petrol prices by >Rs.5/l and diesel by a couple of Rupees. Votaries of free market can stop reading at this point because as I had suggested in the previous part, the government should just tell the OMCs that they stay happy with a GRM of $6.5/bbl. That would be $8.5/bbl refining margin for both petrol and diesel.

If we go with $8.5/bbl, then what would be the price to the dealer? I am assuming Brent price of $80/bbl though prices have generally remained a few dollars below that level over the last few weeks. Also note that since a large component of our imports are now discounted Russian crude, the average import price should be below Brent ( we also buy cheaper quality, lower price crude vs Brent generally, but not getting into further details). At $80/bbl and $8.50/bbl of refining margin, we can potentially reduce prices by Rs.6–7/litre. But there are two factors which need to be considered as well, one positive and one negative — the OMCs are sitting on huge surplus profits built up over the first nine months of FY 23–24. On the other hand, the OMCs are currently selling LPG cylinders at a loss.

How much surplus profits have OMCs build up?

Let us look at BPCL’s financial performance since the start of FY 22–23. Excluding exceptional items, the company’s profits during FY 22–23 would be around Rs. 5–6K crores. This compares to historical annual profits of Rs.10–12K crores. So that would mean a loss vs historical average to be recouped of, say Rs. 5K crores (not the insane underrecovery figure of Rs.25K crores or ~Rs.20K crores post taxes). How much after-tax profit did BPCL make in 1H 23–24? Rs.19K crores!! Yes, you read that right — they made 1.5x in 6 months vs their peak annual profit historically. If we consider Rs. 13K crores as reasonable profits for FY 23–24, they have already achieved it *AFTER* recouping their losses for FY 22–23. In other words, even if they do not make another Rupee for the rest of the year, they would be fine. But given benign oil prices in Q3 , they should be making outsized profits in Q3 as well. Short point: the company is sitting pretty as far as profits go.

While I have not analyzed the other two OMCs in similar detail, the profit performance broadly follows the same trend as BPCL, as is to be expected.

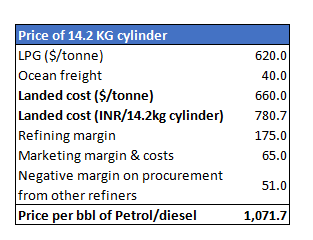

Losses on LPG sales, possible combinations for price cuts

At current global LPG prices, OMCs are making a loss of between Rs.150–175 per cylinder sold. The OMCs have made humongous surplus profits from LPG sales in 1H 2023–24 — as per this article by Devangshu Dutta, those profits are not recorded in the books, the surplus profits are instead placed in an adjustment account to offset future losses. Mr. Dutta estimates the fund has accumulated Rs.12K crores by end-September. I will leave out this part in my analysis since there is no disclosure by OMCs in this regard but if true, it provides further upside to potential price cuts.

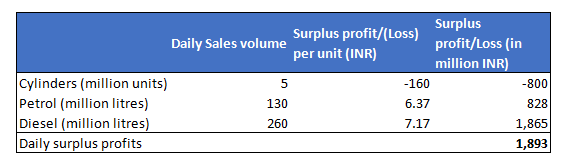

At $80 oil price, this is how I see surplus daily profits earned by the OMCs in aggregate. They collectively make Rs. 1.89 billion of surplus profits every day.

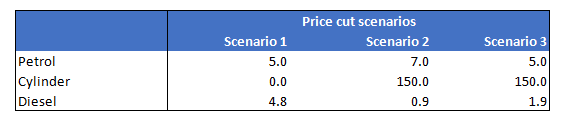

So a price cut can follow any of the following combinations. Politically, a sharper cut in petrol and LPG prices is more preferable ahead of the elections (scenario 2 and 3) while a cut in diesel prices would be better for battling inflationary pressures. And there is upside to these price cuts if one considers that the OMCs are sitting on large surplus profits this year so far. My own preference would be somewhere between scenario 1 & 2 but I would definitely not grudge Modi dipping into the OMC’s surplus proifts and going for a bigger cut. Of course the risk in that case is he will need to revert to more normalised prices by the end of this year. Or horror of horrors, bring down the fuel taxes.

I would like to highlight that I consider these cuts as the floor estimates considering assumptions for the price build-up are quite conservative, whether it be on crude oil landed cost or marketing costs and margins. Apart from the fact that OMCs are already sitting on huge surplus profits.

Postscript: I have grown tired of explaining why these price cuts have no impact on the fisc. As you can see from the analysis above, price cuts do not require even a single Rupee of tax cuts by the centre. Currently, all the surplus profits are just flowing into OMC’s Profit & Loss account.

Appendix — LPG cylinder price math

Source: based on this 2017 PPAC report — domestic costs in 2017 was Rs.120. Should possibly be currently in the range of Rs.150–175 after accounting for inflation