Introduction

A common claim that can be increasingly found in the Indic internet is that the steppe ancestry found in modern day Indians with significant frequency entered India in the late Iron Age and/or the Early Historic Period. Dr Niraj Rai has implied as much in interviews, and Ashish has championed this theory, recently identifying a sample in Iron Age Turkmenistan as an example source of ancestry for modern day Indians.

I previously responded to these claims on Twitter and am here restating my arguments together with some additional analyses. To begin with, we must understand the geography of gene flow from the steppe, whether via migrations or via inter-marriages.

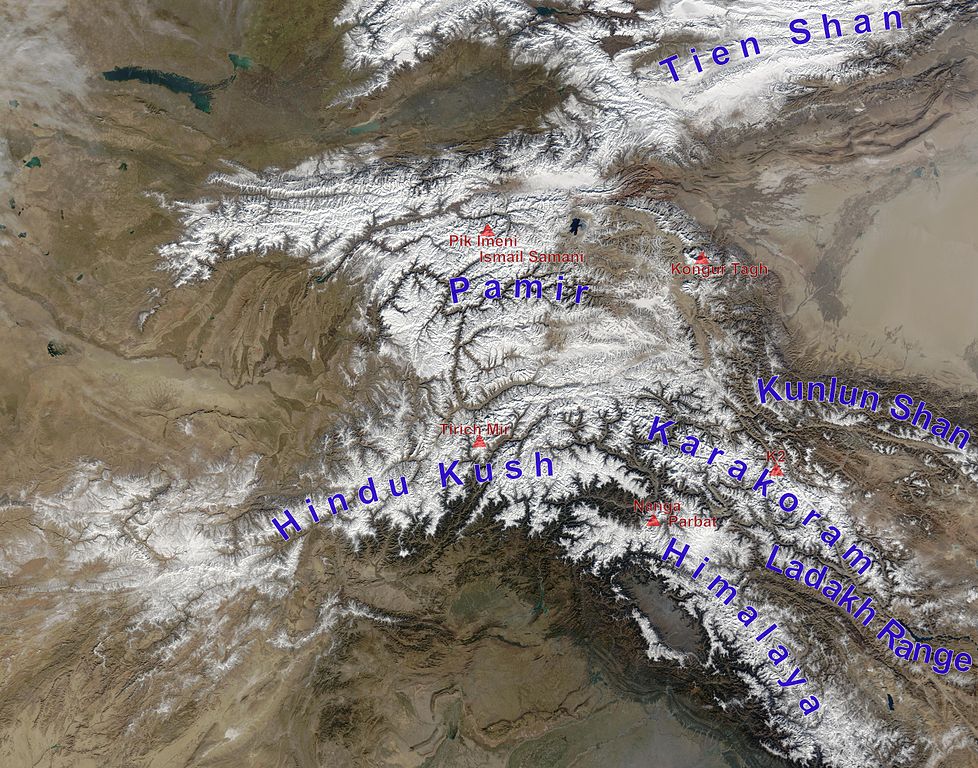

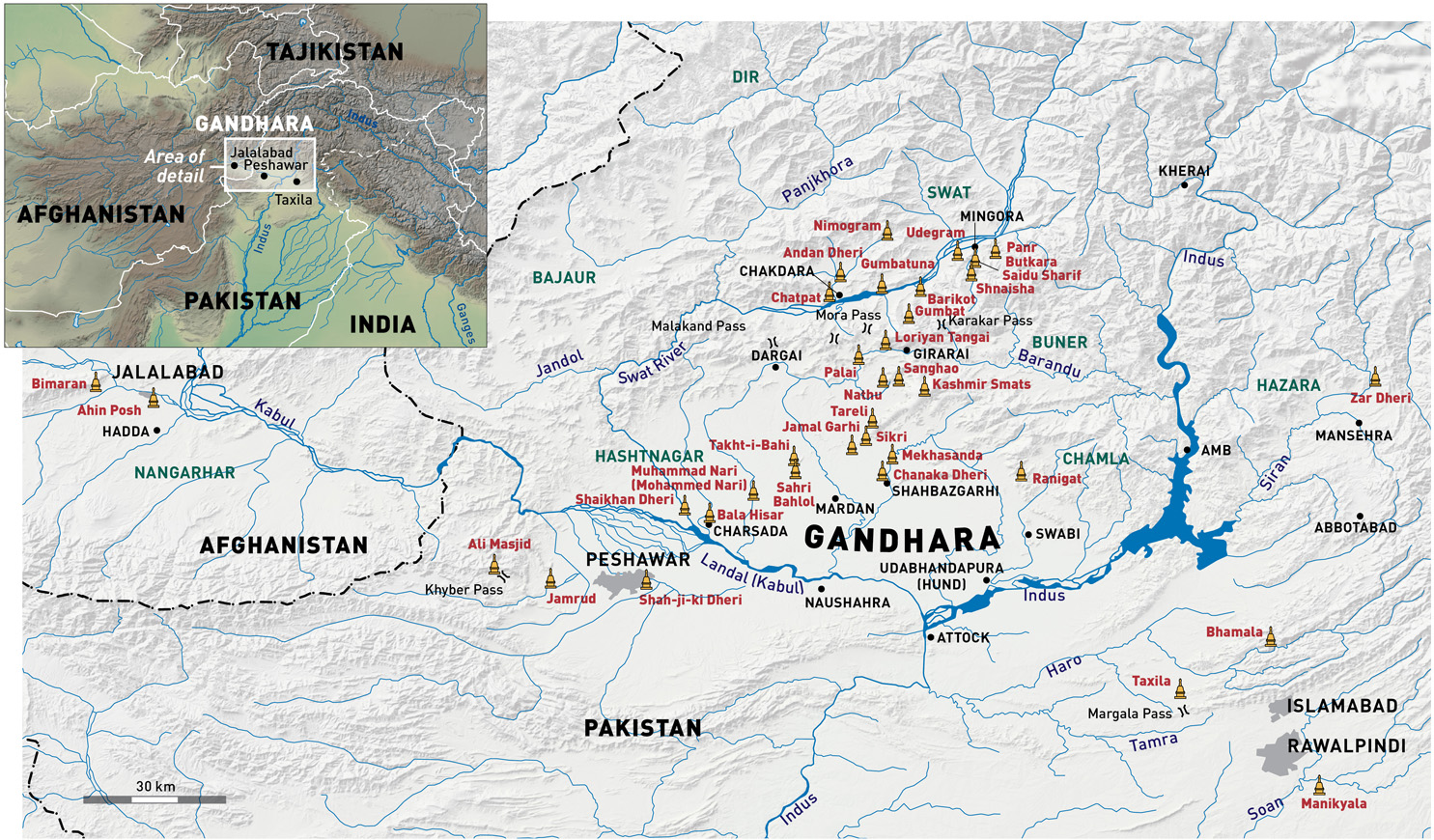

Geography of migrations

Here are some maps of the northern end of the Indian subcontinent. Notably, the Hindu Kush mountains formed a barrier between Gandhara and the areas north of it – travel through this area in large numbers was quite difficult. Instead, travelers from the steppe would travel around the western tip of the Hindu Kush mountains, heading southeast from Balkh to Kabul/Begram through semi-mountainous lands, and from there heading east down the Kabul river valley into the Vale of Peshawar via the Khyber Pass, to the city of Pushkalavati at the Bala Hisar / Charsada sites. From there, they could head down the Indus Valley or more commonly further east to Taxila, before continuing on towards the Ganga Valley. An alternate route would travel around the semi-mountain regions of Afghanistan, heading south from Herat to Kandahar, and then southeast from there via the Bolan Pass into the middle of the Indus Valley (i.e. roughly the Punjab-Sindh border).

Either way, the Swat Valley in the mountains north of Gandhara was not a stopping point along the route into India. Furthermore, the Swat Valley was not directly part of the general Indian geographic sphere, which extended up to about Shahbazgarhi. In many ways Swat’s relationship to the Indus Valley was akin to Nepal’s relationship to the Ganga Valley – significant trade and cultural contact but also some degree of genetic differentiation.

As such, we would expect steppe ancestry to have entered in greater proportions into Indo-Gangetic Plains than in Swat – especially into Punjab. In fact, that’s exactly what we observe in modern populations. The highest steppe ancestry modern populations are Punjabi / Haryanvi Rors and Jats.

To ascertain the timing of steppe admixture, ideally we’d have ancient DNA samples from the relevant time periods in these regions to check directly for steppe admixture. However, due to a mixture of climate issues, underfunded archeology, and a culture of cremation, there is a total dearth of relevant ancient DNA samples. Instead, we must rely on what samples we’re able to find and utilize the DATES tool to estimate admixture times.

DATES Estimates

Interpreting / theory

Now, to interpret DATES results, we must keep in mind particularly with an incompletely admixed population such as India’s, that admixture times can be much later than migration times. When Indian-residing groups with elevated steppe ancestry interbreed with those with low steppe ancestry, their intermediate steppe ancestry offspring will show more recent admixture. This does not mean the steppe migration occurred at the time of admixture, but rather that admixture continued after migration occurred. As such, admixture times are lower bounds, not mean estimates, for the timing of migration. In the Indian context, we must look to older samples as well as groups with early caste endogamy to discern the true time of migration, without the confounding effects of later intermingling.

Additionally, when modeling with DATES, preference should be given to the model that provides the narrowest estimates. Per Chintalapati et. al., a model is considered to be valid if the Z-score is > 2, the normalized root mean square deviation is below 0.7, and estimated number of generations is below 200.

To model the sources of admixture in DATES, I’ve used Sintashta-Petrovka samples for the steppe source (both sets of Sintashta samples as well as the Petrovka sample available in the Reich database) against the AASI-proxy used by Narasimhan et. al. (STU.SG, ITU.SG, BIR.SG) plus Irula.DG and Pallan-like Roopkund outliers. Using the relatively pure Sintashta-Petrovka samples instead of Central_Steppe_MLBA particularly reduces the noisiness of DATES modeling in the single target sample modeled later here.

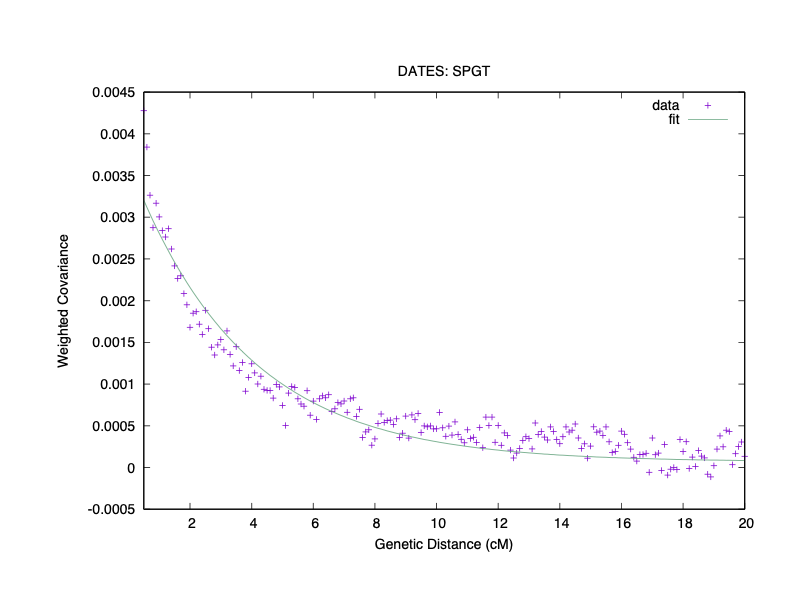

We can sanity check this model by testing admixture times for steppe-enriched Iron Age Swat samples and ensure the results are calibrated in line with the Narasimhan paper:

mean: 27.970 std error: 2.691 Z: 10.394

nrmsd: 0.055

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 1853-1552 BCE

This yields a good fit that’s pretty much identical to the Narasimhan paper and indicates that steppe ancestry entered the Swat Valley in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE.

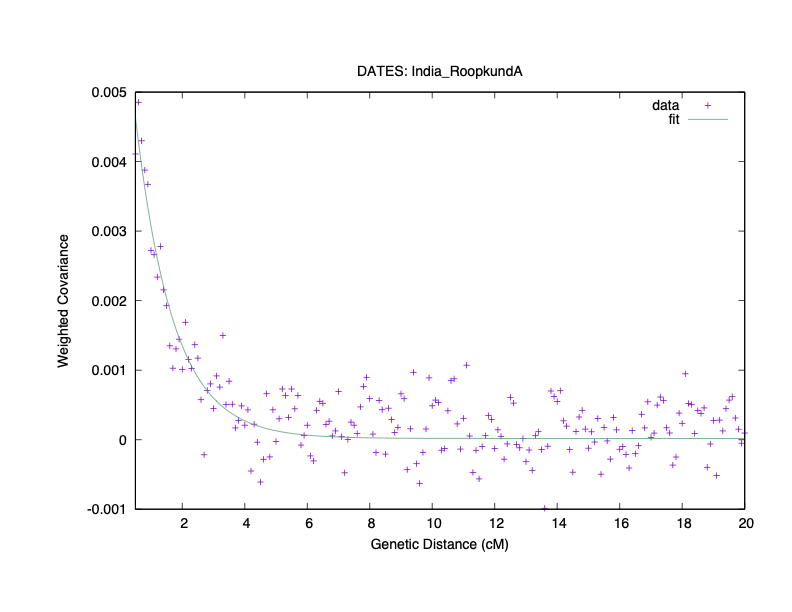

In Roopkund

To find a bound on the timing of admixture in mainland India, we can examine one of the few sets of premodern DNA samples – namely, a collection of pilgrims who had succumbed to hailstorms in the 8th-10th centuries CE in Roopkund Lake. The skeletons sequenced here had a variety of steppe ancestry and included several individuals with relatively high steppe ancestry who clustered with modern day Brahmin Tiwaris.

mean: 84.592 std error: 10.206 Z: 8.288

nrmsd: 0.100

Sample date estimate: 850 CE

95% interval admixture estimate: 2091-948 BCE

The fit is excellent and the results are highly statistically significant. We see clear evidence that the Roopkund samples obtained their steppe admixture in the 2nd millennium BCE and became relatively genetically isolated by the start of the 1st millennium BCE.

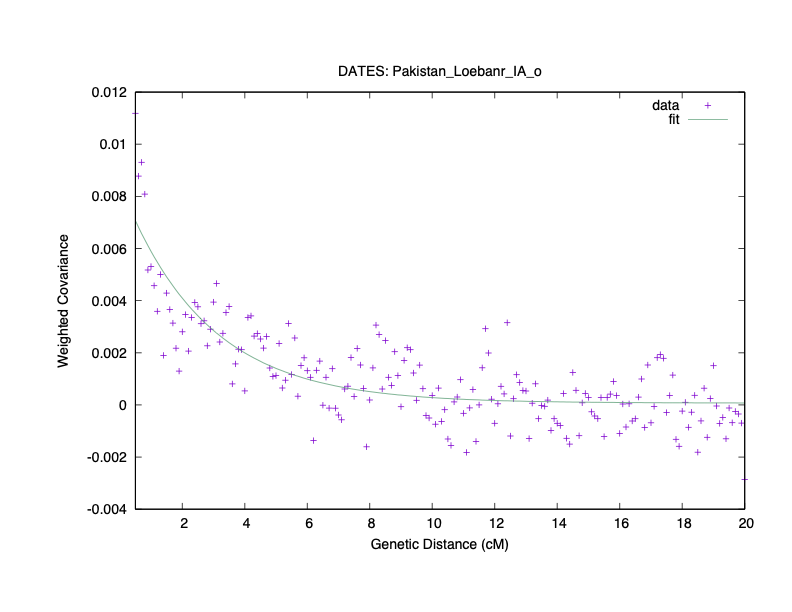

In Loebanr outlier

Now, we can look at one outlier Iron Age woman from the Swat culture who had particularly high steppe ancestry, and appeared to be an individual at the far end of the ANI cline. This woman proved to be a better proximal source of steppe ancestry for modeling modern day Indians than her Turkmenistan contemporary (another single sample that has been proposed as a source of late steppe ancestry). Where did this woman come from? Punjab would be a good bet. After all, her significant amount of AASI in combination with a relatively low Anatolian neolithic ancestry argues against a location in Central Asia. And modern day Punjabi / Haryana Jats and Rors are not far removed from her – e.g. I modeled a Haryanvi Ror sample as 16% Irula and 83% ancestry from a population akin to this woman. Therefore, it’s likely she was a migrant up from Gandhara or further south and can be used as a representative of higher caste Punjabis of her time.

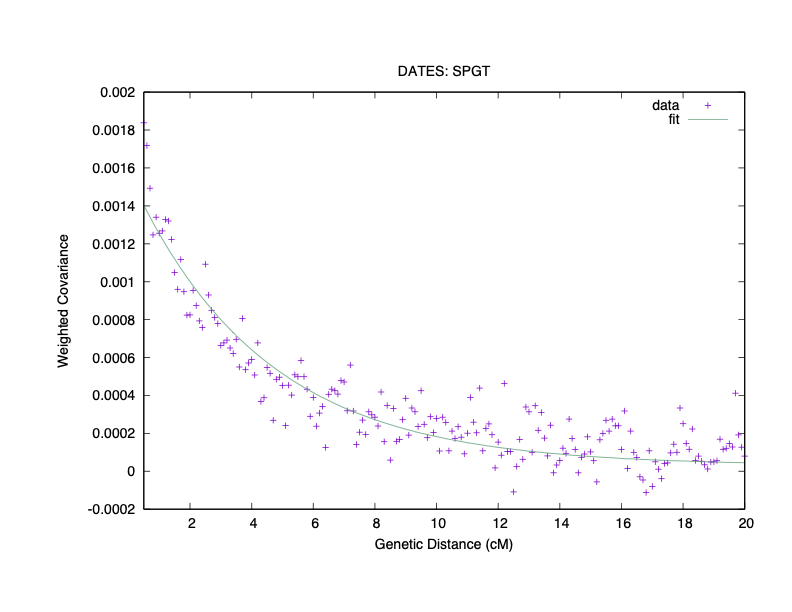

Let’s look at the DATES modeling for this woman:

mean: 37.593 std error: 13.239 Z: 2.840

nrmsd: 0.191

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 2714-1231 BCE

As is normal for a single sample, the data is somewhat noisy. Nevertheless, DATES is designed to be able to handle single target samples, and we have a good nrmsd score and a statistically significant result, albeit with a wide range. This would confirm that the woman came from a large population that had been well formed by the late 2nd millennium BCE. More crucially, the weighted covariance at large genetic distance is close to 0, indicating she was not for example a product of recent marriage between a high steppe migrant from Turkmenistan and a lower steppe inhabitant of Loebanr. However, let’s obtain a narrower estimate of admixture time.

IVC-related as source

To improve the fit, in light of the low AASI proportion in the Loebanr outlier, we can use IVC and similar individuals high in neolithic ancestry but lacking in steppe ancestry as the source. For this group, I’ve used the IVC periphery samples in the Reich dataset, along with Aligrama (Iron Age Swat samples without steppe ancestry), and SiS-BA-1 (non-Indus-periphery samples from the Helmand culture, which have India-related ancestry).

Once again, let’s check calibration against the results from the Narasimhan paper:

mean: 24.077 std error: 2.658 Z: 9.059

nrmsd: 0.101

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 1743-1445 BCE

The nrmsd is somewhat worse but the results are essentially in line with the modeling using AASI-rich sources.

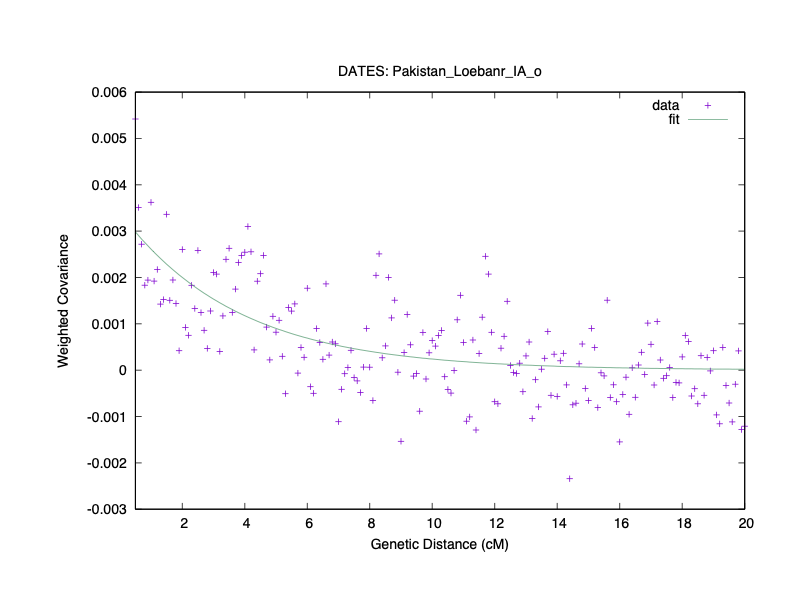

Now, let’s give it a go on the Loebanr outlier woman:

mean: 27.621 std error: 5.222 Z: 5.290

nrmsd: 0.356

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 1986-1401 BCE

Due to noise, nrsmd worsened but is still well below 0.7. Notwithstanding this though, the shape of the curve fits like a glove and appears spot on with the average weighted covariance. And that good curve fit is reflected in the improved Z score and lower standard error. The result lets us conclude that the Loebanr outlier woman received her steppe ancestry admixture at roughly the same time as her Swat Valley contemporaries did.

Conclusion / Implications

To conclude, we’ve found evidence that high steppe ancestry may have reached the Ganga Valley by the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, and likely had reached Gandhara / Punjab by the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. Some of the steppe ancestry that entered Gandhara also traveled up into the Swat Valley in the same timeframe.

All of this evidence is consistent with steppe ancestry settling in the Punjab centuries prior to the composition of the Rigveda there, in conjunction with the observed spread of R1a-L657 in India which originated from the R1a-Z93 Y-haplogroup of the steppe. It’s also consistent with the beginning of formation of caste groups in the Kuru-Panchala Kingdoms around the time the varna system began to be implemented in the Iron Age Late Vedic Period.

We may also hypothesize that perhaps the people of the Swat Valley spoke old Burushaski. After all, the modern day Burusho people are located in the mountains further uphill from the Swat Valley, and genetically have some traits in common with the non-outlier samples of the Swat – viz. lower Sintashta ancestry and elevated IAMC (Aigyrzhal-like Inner Asian Mountain Corridor) ancestry. They have additional East Asian ancestry but this is consistent with a population that would have had trade links to the Tarim Basin, and the observed presence of Turkic and Tibetan loanwords in the Burusho language.

Note that while the evidence here indicates that there had already been substantial steppe admixture into India in the Bronze Age, it does not preclude additional later admixture of steppe ancestry in the Iron Age or Early Historic Period. Substantial admixture in this period is unlikely for a few reasons: lack of admixture from East Asian or Anatolian heavy groups (why would the groups resembling earlier steppe populations be the only ones to admix into India?), lack of migration of newer steppe-originated Y chromosome lineages, and the sheer size of the growing Indian population which would lessen the relative genetic contribution of migrants. But regardless though, the presence or absence of additional late steppe admixture does not have much of a bearing on the debate regarding the origins of the Indo-Aryan languages.

….To conclude, we’ve found evidence that high steppe ancestry may have reached the Ganga Valley by the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, and likely had reached Gandhara / Punjab by the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE…..

The stratigraphic layers for the period 2500 BCE to 1900 BCE are extremely well preserved due to a combination of factors, namely – they are deep enough to escape the denuding effects of modern anthropogenic activities, climactic aridification after 1900 BCE produced a “still zone” that delineates the period.

Pottery, weapons, domesticated animals, crops, metal artefacts, urbanism follow well defined curves of anthropological progression. Zero abrupt intrusion….like Greek influence in 300 BCE or Roman trade in 100 AD.

What archaeological culture do you have in mind for your intruders in 2500 BCE?

After reading this piece, I see that the accumulating weight of non-trivial pointers (IVC sites on Saraswati, lack of non-IE toponyms, wheat/barley cropping, bovine domestication) are forcing your hand. It’s a slide, but not convincing. You also did not tell us how the Rakhigarhi woman has no Steppes ancestry.

You have also worsened the “genetics vs archaeology” paradox – which is that the most profound cultural, sociological and linguistic changes on the Indian subcontinent happened 4500 years ago and….since then it is stagnation!

While the greatest archaeological intrusions happened in the 500 BCE to 500 CE period (Achaeminids, Greeks, Scythians, Hunas) and the geneticist position is that they contributed nothing to the Indian ancestral makeup.

We need parsimony and coherence!

The 2nd Millennium BCE is 2000-1000 BCE.

Of course! Steppes people did not land at Ambala airport.

The Corded Ware culture took approximately 200-500 years (based on various estimates) to intensify over the extent of continental Europe (slightly over 2000 kms span). That is roughly 4-10 kms per year.

You are not stating it but it is implied throughout your piece. Straight line distance (highly unlikely in the Bronze Age) is 1500 kms between Western Afghanistan and Amritsar. A more realistic distance is the motorway line which is a whopping 2500 kms (goes around mountains). What is your claim for the date chain?

I only see a 2500 BCE entry into Afghanistan/Tajikistan as the prior for your claim of 1500 BCE in “Gandhara/Punjab”.

Longitudinal and Latitudinal migrations need not have same rate of progression.

The Gangetic expansion once it started was quite rapid, combing Longitudinal/East-West coverage plus Gangetic valley itself aligned in that direction aiding that movement (plus these people being off-spring of those who had already relatively adapted to North Indian climate when being near Punjab region).

Coming from Central Asia to Punjab without a doubt couldn’t have happened fast, the Latitudinal climate change is way too much to adjust in single generation if not even more.

@Var

Rapidity and materiality are two different facets. There are no less than 300 journal papers showing the spread of CW into Europe with high-fidelity field excavations. Where is the equivalent for the Indian subcontinent? There is strong archaeological consensus of no incursion into India from the Northwest during 2500 BCE to 1500 BCE.

Addendum: The British, after having landed on the Southern and Western coasts of India, took a little over 200 years to completely dominate the political landscape and overturn the linguistic hierarchy (Persian/Hindustani to English). This is in the modern era of gunpowder and steel.

I commented before, but the site is so buggy it doesnt work.

Nice post, one clue is also found in the bustan post-bmac BA2 outlier (I11520). It’s radiocarbon dated to 1500 BCE and has an ancestry profile similar to modern NW Indians (IVC + Steppe + AASI, Y-DNA – R2a). I don’t think this is an accidental similarity at all.

Second, for the SPGT samples, I talked about this with you too, but that set spans 1000 years and is not homogeneous at all. I extracted them individually and ran them on harappaworld, their oracles show they are closest to modern dards like kalash desite having much lower sintashta mlba. Some of them are Proto-Pashtuns, and others are even Proto-Jatts with 35% Steppe (I6893). Some are like Punjabi Chuhras, others like South Indians and have 4-5% steppe.

I believe most of the SPGT people are from castes that didnt survive into modern times. India has strict endogamy, so no group existed that isnt boxed into a tribe or caste.

https://vritrahan.blogspot.com/2022/12/the-swat-protohistoric-samples.html#comment-form

Yes, a reasonable alternate theory is that the outlier woman came from a high caste subpopulation in Loebanr itself. Perhaps even one that was predominantly cremated (when a culture has a mix of burials and cremations, we can’t be certain that the buried remains are representative).

The conclusions would still be similar (there was a high steppe population in India quite early), and the route taken to get to Swat would have still taken the steppe migrants through Gandhara (which has a related grave culture during this time period – to the point that early archeologists who focused on grave similarities labelled the whole area “Gandhara grave culture”).

Regarding the endogamy though, I think the evidence is not yet clear on the extent to which North India / Ganga Valley practiced endogamy before the 1st millennium BCE. We certainly see some evidence of it in Swat (with Aligrama samples having minimal steppe ancestry compared to other sites).

And yes, good call on the Bustan outlier. Definitely fits the bill as an early admixed Indian.

Now if only Niraj Rai publishes the Burzahom aDNA in a timely manner…

Wait, while I agree but there is a issue, how do you explain such high NE Euro component/steppe ancestry in Chitralis Khos, Wakhis and some Pashtuns as well? Many of them even score higher then Rors. I have seen one Wakhi scoring 29% NE Euro on Harrapa, and several Chitralis on Harrapa have scored over 20% Caucasian and 20% NE Euro together. Some Pashtuns also have scored well over 20% NE Euro? I mean clearly the high Steppe people must have gone up that North

You guys are confusing Steppe DNA with Gujarati DNA.

There is an expansion from Gujarat-Sindh region. Sindh is where Rors came from hence their higher Steppe ancestry.

The ‘new’ DNA from Gujarat is moving into Sindh (Rors) then up the Indus and then into Central Asia, which is where Steppe DNA is located.

The variation in South Asians, and Swat Valley samples, is not best described by DNA from Steppe, it is best described by DNA from Gujarat region.

Because DNA from Gujarat-Sindh moved into Steppe, that DNA is being labelled as ‘Steppe DNA’ because the compute doesnt know where it came from, we just call it Steppe.

But f4 stats of the form f4(South Asian, South Asian) (Test, Chimp)

will always score higher when Test is Gujarati (or Ror) than Steppe DNA.

So f4(x, y)(test, chimp)

if x is say a moden ‘High Steppe’ South Asian and Y is ancient/modern low-steppe sample, will still have Gujaratis scoring higher than Steppe DNA. Thus it is RECENT NW South Asian like Gujaratis, Sindhis, Ror who contributed most ancestry to RECENT Steppe groups, and also dispersing across South Asia. This NW South Asian nomadic expansion, which has been on-going for atleast 10K years, is just being confused with Steppe DNA, because Steppe also has this input in very large amounts.

Because Jatts are agropastoral, and Ror were likely Nomadic, agropastoral Steppe MLBA has more Jatt than Ror, and Yamnya/Afanasievo has more Ror than Jatt afaik.