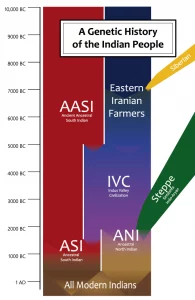

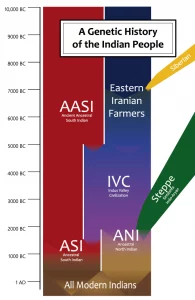

The figure to the right is from a Substack post I wrote last year, Stark Truth About Aryans: a story of India. In it, I posted about the different streams of ancestry that led to the variation in the modern Indian subcontinent. In short, there are three primary threads:

The figure to the right is from a Substack post I wrote last year, Stark Truth About Aryans: a story of India. In it, I posted about the different streams of ancestry that led to the variation in the modern Indian subcontinent. In short, there are three primary threads:

1) Steppe Indo-Aryans who are identical to the Sintashta Culture of the upper Volga ~4,000 and gave rise to the Andronovo Horizon

2) “Ancient Ancestral South Indians,” who have more affinity to the peoples to the east of Eurasia, and are distantly related to a clade of humans that brackets the Negritos of Southeast Asia, the Andamanese, and the people of Australia (this clade diversified between 35 and 45 thousand years ago, so these are not close connections). Though the modern Andamanese are often used as a substitute for AASI, the reality is that they diverged more than 30,000 years earlier and these tribal populations probably derive from modern Burma, rather than India (the Andaman Islands are an extension of the Burmese geological formation).

3) Lastly, there is a component that has been termed by some as “eastern Iranian,” but really defines a little-understood population that represents the easternmost extension of the Zagrosian farmer stock. These eastern people that extended likely into the northwest of the subcontinent are distinctive in that they lack any admixture from Anatolian farmers, which is ubiquitous to the west of Dasht-e-Kavir. Not only do these people not have any Anatolian admixture, but they also have enrichment for Paleo-Siberian ancestry, likely mediated along the pastoralist fringe of Central Asia

The vast majority of subcontinental populations have some thread of ancestry from these three groups. The major difference is proportions. You can see this in an admixture graph I ran a few years ago (yes, I need to update it). In the graph AHG = AASI, while steppe is pretty straightforward. But, the Indus_Periphery group is a mix of “eastern Iranian” and “AASI.” Concretely, I simply picked the highest quality and least AASI samples to capture as much eastern Iranian ancestry as I could. But I would estimate that 10% AASI is still a rational lower-bound (probably not higher than 20%) estimate for my Indus_Periphery construct. This means even the Kalash of Pakistan, who are ~0% AHG in my model, do have AASI ancestry, it’s just mediated through their 70% Indus_Periphery.

In regards to the steppe ancestry, the reality is that it is present across the vast majority of groups. The exceptions are a very few South India tribal and most Munda populations. Groups like Reddys and Nadars will clock in at 5-10% steppe ancestry. This makes sense when you note that Y chromosome R1a1a-Z93 is found in even tribal groups with the exception of the Mundas. There are other details that are curious. Many groups in the Sindh/Gujurat region are very enriched for Indus_Periphery but have very low AHG proportions and less steppe. In contrast, some Gangetic populations have far more steppe than these, but far more AHG.

This brings me to the point of the post: when people say that Dalits or Adivasis are the indigenous people of the subcontinent, I think it does not necessarily have as strong of a human demographic basis as one might think. That is because to a great extent Dalits and almost all Adivasis are made from the same threads as other subcontinental populations, even if the proportions may differ.

Let’s walk it back and understand the ethnogenesis of the subcontinent.

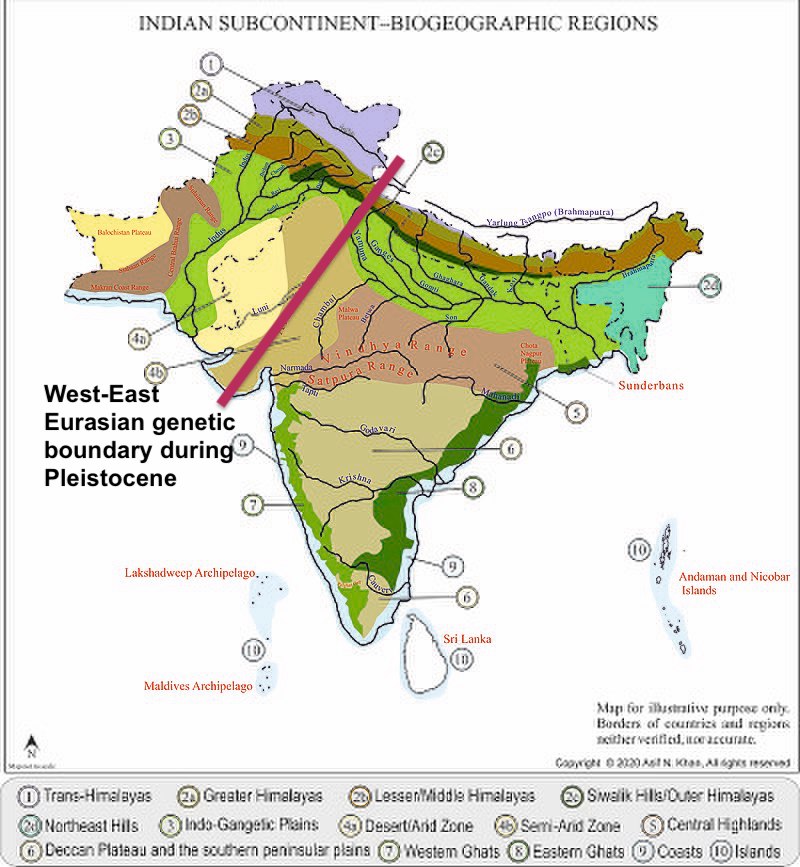

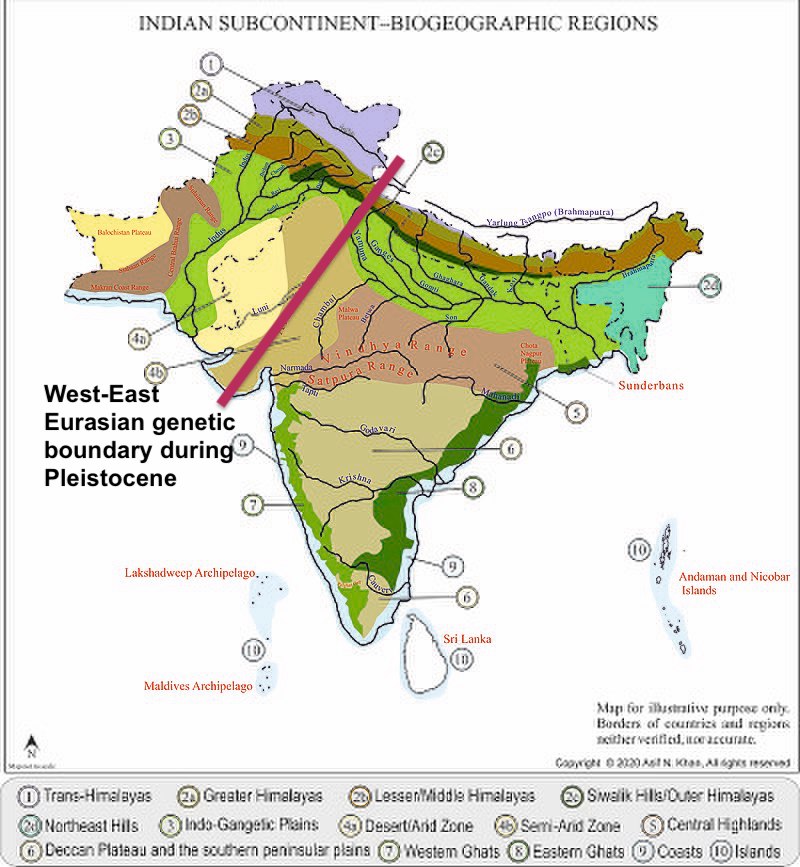

First, it is quite possible that the AASI are not indigenous to the portion of the subcontinent to the north and west of the Thar desert. Their natural ecological locus was likely in the east and the south. Biogeographically the northwest of the subcontinent is somewhat different than the south, center, and east, which resemble Southeast Asia more (albeit at a remove). During the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Thar Desert was drier and larger, serving as a boundary zone between southwest Eurasia and southeast Eurasia.

The ancient DNA from the Swat valley as well as the genetic character of modern Punjabi populations compared to the ancient samples from the IVC make a strong case that AASI ancestry is intrusive to the northwest. By this, I don’t mean that AASI tribes migrated in that direction, rather, as the IVC expanded it clearly mixed with AASI populations to its south and east, and as the IVC was an integrated cultural zone, mixed individuals moved north and west over time.

The Swat transect shows a decrease in IVC proportions between 1000 BC and 0 AD, and increased steppe and AASI ancestry. This is part of what I call the “integration phase” of Indian civilization, as gene flow occurred not just from the northwest with Indo-Aryan expansion, but Indo-Aryan reflux migration must have occurred into the west. These eastern Indo-Aryans mixed extensively with indigenous people in the Gangetic valley, explaining why Brahmin populations in this region have noticeable more steppe ancestry than groups like Sindhis, but also far more AASI ancestry. Indo-Aryan tribes all mixed with IVC people when they arrived in the subcontinent (while there are populations that are ~0 steppe, and others that are ~0 AHG, there are no populations in the subcontinent that are ~0 Indus), but a subset moved east and south fast so that they arrived with a higher steppe fraction when they settled down to mix with indigenous tribes.

Second, even outside of the northwest, it is not entirely clear that the AASI is not a recent early Holocene migration from Southeast Asia. Genetically they are part of the continuum with the indigenous Negrito people of Southeast Asia. I think it is less likely that there was massive Southeast Asia migration during the Holocene, but for most of the Pleistocene, Southeast Asia had many more humans than India because India was far drier.

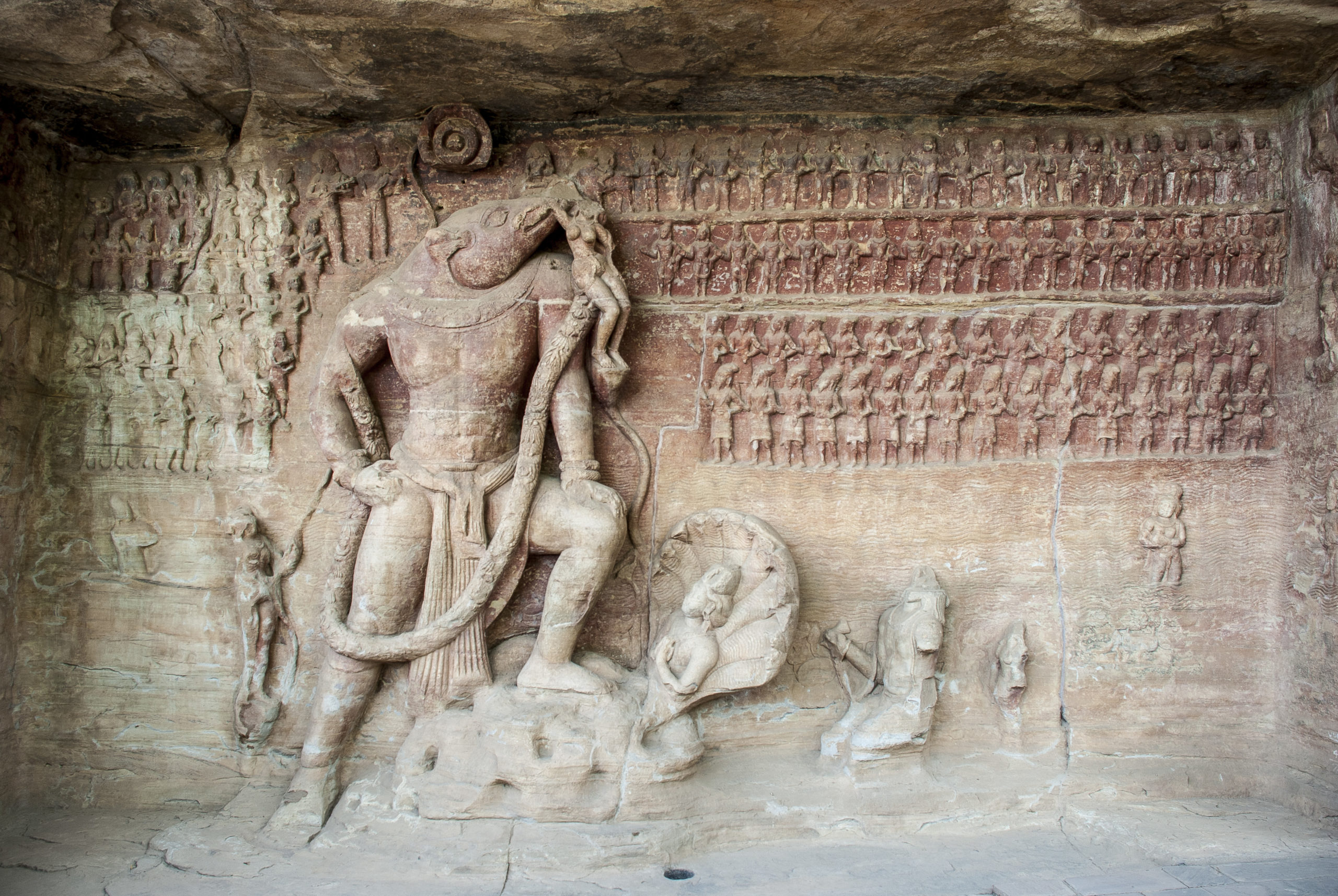

Finally, outside of exceptional groups like the Munda, whose language and mythology seem derived from the 20-30% of their ancestry than is Austro-Asiatic Southeast Asian (and all-male), almost all subcontinental populations come out of the cultural matrix whereby Indo-Aryans synthesized with indigenous populations (much, but not all of whom, were Dravidian-speaking). The earliest Tamil has a clear Indo-Aryan influence, while the retroflex in Sanskrit is indicative of Indic influence very early on.

Where am I going with this? Genetically a Jat from Haryana is very different from a Dalit from Tamil Nadu. A Jat is 10-20% AASI (aggregating the AHG estimate with the AASH fraction in the Indus_Periphery), and 25-30% steppe. The Dalit is 75% or so AASI (again, aggregate), and only a few percent steppe. This is a massive genetic difference. But culturally it is clear that both come out of an Indian milieu that was shaped in the period between 1500 BC and 500 BC, as the Indus Valley Civilization collapsed, and its remnants were transmuted by Indo-Aryans. The tribes in the north that continued their Indo-Aryan language were clearly transformed, but the Dravidian-speaking polities of the south were also imprinted by the Indo-Aryans. It was reciprocal.

Both light-skinned northern Indians who like to claim “actually” they are “Iranian” and dark-skinned South Indians who claim to be “indigenous” emerge out of this process, this dynamic. And they share equally within it. India came out of the mixing of many disparate elements which then disaggregated in various ways, but all went through the same sieve.

In the

In the