The early 2010s saw the internet (particularly youtube) filled with “Takedown” videos of famous public intellectuals and debaters of the likes of Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro. These figures typically have a contrarian take, rhetoric flourishes, exuberant confidence, and sometimes even persuasive arguments. As Youtube and Takedown videos become popular in India, one individual has made more waves than most others — J Sai Deepak – a lawyer cum debater.

India that is Bharat was published 4 months ago and has created quite a buzz — which isn’t restricted to social media. The book is a bestseller on Amazon with 1584 ratings with an average of 4.8. Even on the conservative Goodreads, the book is rated at 4.55 after 167 ratings. I decided to review this book in detail after a few recommendations, especially as I feel people to the liberal side of me in the Hindutva — Liberal Overton will not give this book the honest assessment it deserves.

India that is Bharat is book 1 of a trilogy that seeks to set the foundation for the arguments J Sai Deepak is going to put forth in volumes 2 and 3. The basic premise of the argument (i am paraphrasing) is that events from the 15th century to 19th century Europe that shook the world led to universal definitions of concepts like “Modernity”, “Secularism”, “Equality” and “Rationality”. The author claims that these definitions were fundamentally shaped by the Protestant reformation and underlying Christian morality and are hence “Christian”. In addition, these values went hand in hand with the 18th and 19th-century colonization of Bharat, the legacy of which is still ubiquitous in India. For someone who is even superficially well-read on these topics and has an open mind — this claim is not unsupported (though one could argue on the fine details). The clarity of thought of the author is at display in every word of the book. The book is not a scholarly exercise but a precise multi-utility instrument at the disposal of the ever-growing Indic consciousness movement.

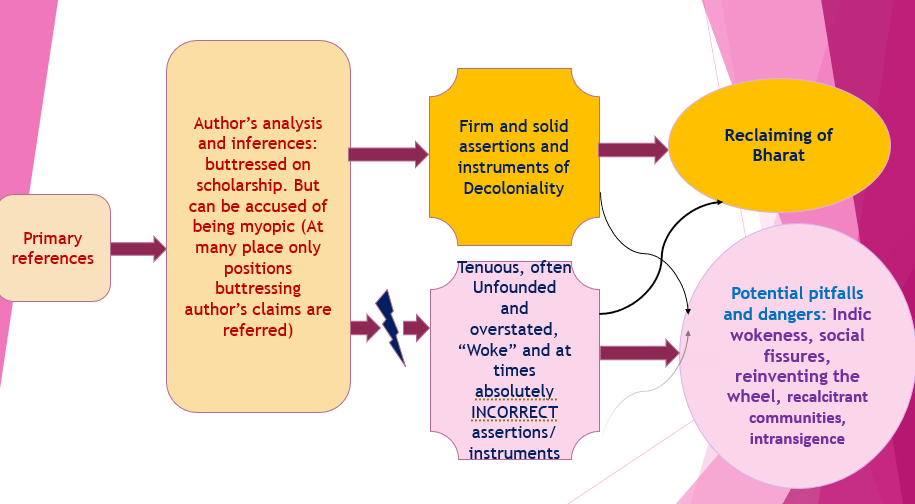

Having accepted this basic premise, the 4 “schools” thought to address it are — Modern, Post-Modern, Postcolonial, and Decolonial, of which the author clearly favors “Decolonial school” as it addresses the “Protestant” elephant in the post-colonial nation-states — Coloniality. The book is divided into three sections, Coloniality, Civilization, and Constitution; each of which is expanded using primary references juxtaposed with the author’s insights. The references give the narrative authenticity but those need analysis and extrapolation which the author goes on to provide with surgical precision with a clear end-goal. In most cases, the analysis of the primary references is convincing and solid (though there are some glaring misses — will expand on them later). The extrapolation from even the most solid inferences is however hit and miss. Like the author, I would also attempt to break my review into three neat sections — the Good, the Bad, and the Overstated.

the GOOD:

The immense work put into building this narrative doesn’t escape the reader’s attention. Especially the argument put forth in the final chapter — “the standard of civilization” is a compelling one and doesn’t often get recognized in the public international discourse. A lot of the issues from that very framework continue to haunt countries like India under the veil of international consensus. The author also does a good job of convincing the reader that seeing India as a “civilizational state” is wishful thinking at best. The author also convincingly brings the various points of divergence between India/Dharmic and Christian/Protestant thinking. It is undeniable that this divergence brought about both the direct and indirect stereotyping of “Hindoos” and their “traditions”, the legacy of which the Hindus of the 21st century have to countenance. Eg: The academic mainstream thought of viewing the Sramana traditions (and to a lesser extent Sikhism), primarily as revolts against Brahmanical orthodoxy (of Varna)— similar to the Protestant Reformation against the Catholic church. Also, the Essential practices test applied to Hindu Sampradayas with emphasis on the written word.

Another interesting point brought forth by the author is the difference in attitudes towards non Humans (nature in general) between the Abrahamic faiths and Indic faiths. What the author didn’t touch upon, but could have added is the attitudes towards Darwinian evolution are also in great divergence in these two OETs (onto etymologies) of Western and Eastern faiths. If a man is a part of nature, evolution is easier to digest. Sadly this harmony with nature which takes the form of worship of nature is seen as a joke in the Abrahamic OET. (Though I do not concur with the author in fullness that a lot of current problems with environmentalism come out of this universalism).

In general, the primary references in the book are well researched and the inferences drawn from them are robust and provide a solid foundation for an interested reader to extrapolate. Constituent assembly debates, House of common debates are presented tersely enough to get a moderately deep understanding of the discussions at hand.

However, the biggest positive contribution of the book is that it recognizes “Coloniality” as an impediment to the realization of Indian(particularly Bharatiya) potential. The continued and blind aping of the west — be in food habits, dress codes, language policy all prevent the confidence of the native from growing. Good communication is often correlated with good English in most fields where the institutional imprint is high (from the Tech industry to journalism). I can tell this from first-hand experience that the country has lost thousands (maybe lacs) of brilliant and honest minds, who are not “Modern” in their outlook, do not get the necessary support from society in general and institutions in particular. Nowhere is this more self-evident than in the Supreme court and English media journalism. Mediocre yet articulate English-speaking elites have suppressed the talents from the subaltern sections of the society from rising up.

the BAD:

Having said the above, I have profound problems with a lot of narratives in the book. My primary problems (as well as support) with the narrative are illustrated below

Below are a few of the numerous examples in the book which signify the fallacies of the narrative.

- In a robust argument about Colonial ethnic cleansing/genocide of Native Americans, the author lets slip the following UNREFERENCED line — which is not just an exaggeration but an objectively falsifiable statement.

In some cases diseases, such as smallpox and the plague, were introduced with the knowledge that the indigenous community was not immune to them.

Kindle location 1054

2. The author addresses the Christian/Colonial framing of the Jati-Varna system by quoting the works of Nicolas Dirks’ among others. While the Colonial reading of Jati-Varna which became the modern Caste System is refuted; the alternative hypothesis for the reality of the Jati-Varna system is missing. The author also completely avoids the recent genetic studies which point to unique endogamy among Indian Jatis which has poked a lot of holes in Nicolas Dirks’s hypothesis.

3. In general the references to and inspiration from Greco Roman culture in Enlightenment are largely omitted while its Protestant roots are overemphasized.

It abounds with works of imagination not inferior to the noblest which Greece has bequeathed to us

Location 5209

A lot of the modern concepts which gained traction in the Enlightenment were clearly of Greco-Roman (or even Indian, Persian) origins. While these may be denied by a section of Christian thinkers in the past (and even so today) — that is not true for the mainstream Western scholarship.

4. It would be fair to assert that the nuance of piecemeal and incremental progress (which incidentally the author might support as a legit way of native reform) has been put through the post-modern lens. Eg: The takedown of Emmanual Kant and his Christian worldview which encompassed racism.

There are some more examples that illustrate my broader point, but I will not add all of them here. (Maybe I can publish my detailed notes somewhere else if needed). In addition to these specific issues, the major incoherent argument made is the insistence of viewing “Modern” concepts of “Equality”, “Liberty”, “Rationality”, “Reason” as at least quasi Protestant. The natural consequence of this is the call for being “Vary” of these concepts themselves – not just their imposition by Coloniality.

This assertion of erroneous as looking at Englightenment primarily a consequence of Protestant Reformation is tenuous at best. But more importantly, history is rife with Concepts/“Memes” which come out of an OET per se and over time lose connection to the OET itself (to view those concepts from the lens of their germination). The savior/messiah concept seems to have made an impression on Indic faiths from Judeo-Christian OET leading to “Maitreya the messiah” (on may also claim that Hindu Kalki is also a result of that but I am not confident about it). This clearly happened without “Coloniality” as Rome only became a Chrisitan empire later. The same is true for the Crystallization of Islamic orthodoxy which not only drew upon concepts of Totalitarian Assyria but also learning mechanisms of Turanian Buddhism (Buddhist influence of Madrassas).

Ironically the template used by the author to claim that modernity and rationality are Christian (Protestant) is exactly the template used by post-modernists (and now Woke) to classify modernity, science, and rationality instruments of White supremacy. This is also the exact same mechanism used by Leftist scholars and Ambedkarites to dismiss or oppose aspects of Hindu culture under the guise of attacking “Brahminism”.

This is a plain double standard disguised as moral relativism.

Another major umbrage I take to the narrative (at least in the first book) feeds into a post-modern and moral relativist framework for contemporary issues. It is one thing to view the past through moral relativism, but completely different to view and judge different groups in the society using different standards. Concepts of community rights and standards become imperative in such a framework and the author makes it crystal clear in the following passage

Kindle Location 3448-3455

While it would be incorrect to claim that the author’s narrative is attacking individual rights, it is clear “if individual rights are adversely affecting interests of a group then the individual right must be traded off against the greater good”. To bolster this position one might take the example of Sabrimala but let’s take a slightly different and problematic example. Will an individual who stands to inherit immense ancestral wealth lose it because of an unapproved marriage or a lifestyle decision? Will the group interest (endogamy/tradition) trump individual rights? More importantly, how is “group interest” defined? In this framework is Jati endogamy as a tool of preserving ancestral traditions a valid “Group interest” which trumps individual rights (related to property specifically). I am not suggesting that this framework wouldn’t allow individuals to legally marry outside group, but the costs associated with such an activity could be legally recognized. Will the provision in Article 35A for Kashmiri women to lose state domicile be defensible under this framework of Preference for “Group interests” over individual rights?

the OVERSTATED:

The author spends the first section of the book linking Coloniality to Protestant reformation and its ramifications. While the link between the two is undeniable, the emphasis laid on Christian roots of Western civilization, Coloniality, and to an extend Enlightenment is strongly contestable. It is not about whitewashing history but acknowledging how other factors play an important and even at times decisive role in the changes that took place after the fifteenth century. This omission would lead an ignorant reader to put the onus of the New world order emphatically on Protestant reformation and its repercussions while ignoring the other factors.

The author almost spends an entire chapter (10) bolstering the idea that British Secularism (or somewhat even-handed treatment of faiths) is a result of pragmatic and mercantile self-interests and not secular enlightenment principles. This is a classic strawman, for even Anglophiles do agree that the British outlook towards religions in India was due to a pragmatic and mercantile attitude; of first the Company and then the Crown. Quotations from conservative members of an Anglican monarchy (not a secular republic unlike France) and Bishops are used to convey the idea that the British Crown and its parliament were Christian and not secular. While the British Anglican church is always seen as somewhat benign compared to other Protestant denominations, the claim that they are seen as secular/idealist in outlook isn’t true for even the 20th century — let alone 19th century (which the book claims to refute).

This line of argument takes the form of overstatements like “Christian character of Government of India” and “legislative bodies acted with the political theology of Christianity”, “Christianisation of morality” and a lot more with immense emphasis on the Christian side of British coloniality. But if this efficient and well-oiled state machinery secondary or even tertiary plans of proselytization, wouldn’t have managed to convert more than 1% of the mainland Hindu population? (most Christians at the time of Independence resided in Goa, Kerala, and Northeast).

In CONCLUSION:

Overall it is fair to say that the author doesn’t confront the plurality of viewpoints on the topic he is addressing. The rhetorical tools which the author deploys in the audiovisual medium are somewhat blunted in the written word, and this also is a weakness of the book. He makes a persuasive case for Decoloniality despite these flaws, but the argument is far from water-tight. (though clearly, a majority of readers would disagree). Every now and then amidst robust points, the author also displays his tendency for hyperbole like calling retention of Hindu identity of the geography of the majority a paper identity. Not only that, but the author also uses postmodernist (“woke terms”) like “politico-epistemic violence of modernity” which is a red flag for whoever is following the debates around these issues in the West.

The book comes out as a precise instrument and not as an inquiry — which is both its strength and its biggest weakness. To date, I have not come across one legitimate critique of the book, either on GoodReads or Amazon or any digital or non-digital publications. The reason for this is clear though, one side of the ideological spectrum treats the author and his arguments as a pariah or upstart — either too extreme or too mediocre for attention. On the flip side, the other side has and will continue to treat this work as “Groundbreaking”, “Red-pilling” or “even personification of perfection” which seems a stretch even with concessions – especially coming from people who are vastly well-read and more of an intellectual bend than myself. I would argue the people on all sides of the political spectrum taking these positions are either dishonest, myopic, or incompetent. Or maybe it’s that they’re blown away (or repelled) by the personality and rhetoric prowess of the author.

While the readers of this post wouldn’t necessarily agree with all the criticisms I have made above, at least some of the criticisms ought to stick.

Having said that, the book was very important and consequential, especially due to the ingrained coloniality in our institutions and minds (especially the courts). For all its faults, the core argument of the book — that India still has a considerable colonial hangover and needs to shed it to become Bharat — stands solidly by the end of the book. The author has also inspired and convinced me to become more Bharatiya despite my profound disagreements with the book. For context: On identifying with the label “Liberal” over “Conservative”. My position on the liberal/conservative scale has shifted slightly to the conservative side due to my engagements with the author’s (and many other) viewpoints in general and this book, in particular. This book can also be seen as part of the famous Tilak vs Agarkar/Ranade debates that have shaped the Marathi society for the last 100 years. One could say that the intellectual and state pendulum has swung more in Agarkar’s favor and this book is an attempt to wrestle it back towards Tilak.

Given the popularity of the book and the author, the cliche saying “Love it, Hate it but you can’t ignore it” is perfect, to sum up the book in particular and the Decoloniality movement in general. It is definitely a must-read for all interested in public discourse about India that is Bharat.

Post Script:

There may be some errors in my original criticism – especially Point 1 of section the “Bad” which can be worded better. My criticism was about allegation of “with the knowledge that the indigenous community was not immune to them” which was not supported by the author by references. That narrow point stands it is unreferenced but pointed criticism around it I made is wrong.

I was unaware of the scholarship which points that early Europeans may have some awareness of the way immunity works and how the it played in way of accelerating their colonization.

Too many books, too little time, i forgot to buy the book, immediately did so. I have not yet read the book. I have always found something to agree with you on most issues, in this case i dont see much. I will put that blame in my not reading it. So, merely going by this review, i am not convinced. After failing to put my thoughts multiple times so as not to exceed few lines, I have come with a simple way to point this out.

Indian liberals/left have no consistent intellectual position on anything, no principles, they unite only in two ways, one is in their selection for measures of pro western performativity, two, is in their position to take anti hindu disposition. That is it. This behavior is the product best explained by the christian missionary led intervention in India. You should not conflate the western history of enlightenment vs how it was received in India under british colonialism. There is no way to explain the nature of this bizarre behavior.

I will give you an example, a family member, (not the same one as before), boasted about an Indian being a ceo of twitter and how this was due to gandhi, nehru ,congress. I merely pointed out that this success of very few Indians cannot be a true measure of success. I asked him to tell what is India’s gdp per capita and rank in the world. He replied with, “blame hindus for producing more children”.This is the quality of received enlightenment in India, press them with one question and answer is anti hindu jibes.

// 2. The author addresses the Christian/Colonial framing of the Jati-Varna system by quoting the works of Nicolas Dirks’ among others. While the Colonial reading of Jati-Varna which became the modern Caste System is refuted; the alternative hypothesis for the reality of the Jati-Varna system is missing. The author also completely avoids the recent genetic studies which point to unique endogamy among Indian Jatis which has poked a lot of holes in Nicolas Dirks’s hypothesis. //

It does not poke any holes in Nicholas Dirks theories because Endogamy & social interaction does not have to go hand in hand in the same manner as modern sensibilities or understandings of ‘community’. What Nicholas Dirks highlighted was how Colonizers used ‘information gap’ among communities & networks to destroy earlier modes of interactions & understanding among communities & people. Genetics & Endogamy may have poked holes in some of his theories even then the broader argument of his work can not be dismissed or else you will have to dismiss a whole array of works like –

The Colonial Origins of Ethnic Violence

https://thewire.in/books/communal-violence-caste-colonialism

The Great Agrarian Conquest: The Colonial Reshaping of a Rural World

Or

The civility of indifference by F.G. Bailey

– This is village study of Bisipara & shows the modern political transformations it has brought to the region.

50 yr’s of political transition in a single region –

https://www.academia.edu/26812011/F_G_Baileys_Bisipara_Revisited

Let me give you an example from a different field i.e. Persianate studies i.e. Adab & networks.

https://psyche.co/ideas/persianate-adab-involves-far-more-than-elegant-manners

Similarly from Gupta period –

https://www.academia.edu/60764090/Towards_a_history_of_courtly_emotions_in_early_medieval_India_c_300_700_CE

Note – Courtly culture & emotions beyond just power & subjugation.

Point here is that imagining communities in modern times based on political ideologies, economic theories & so on does not mean that it alters the ‘community’ forms from earlier in-egalitarian ways to modern egalitarian ways instead old ways of imagining & negotiation among communities are destroyed violently to impose new categories.

Internal working within new communities remains more or less the same as earlier supposedly in-egalitarian forms – That’s the broad argument i am making.

Some more papers for your reference regarding community, solidarity, Ethnicity, Identity & networks etc. –

https://www.academia.edu/45481712/Kinship_as_fiction_exploring_the_dynamism_of_intimate_relationships_in_South_Asia

https://www.academia.edu/61747824/Community_as_an_Instinct_A_Return_to_Ferdinand_T%C3%B6nnies_view_of_Gemeinschaft_Harald_Tambs_Lyche

Note – Communities are not only imagined but also contextual & instinctive.

On the another end i.e. Elite perspective & Imagined communities –

https://youtu.be/hKgzHccdbwU?t=2204

Watch till – 41 Min approx.

Note – A look inside self deluding deracinated elites debating about Social Structures. The only problem was that they delinked Hinduism completely from politics while allowing all other kinds of identities {Tribe, Caste, Minority etc.} as they framed Indian constitution which they saw as contest between ‘Society’ {Indic Predominantly Hindu} Vs ‘State’.

So if you note endogamy was no hinderence in many pre-industrial societies as many communities interacted, traded & engage each other but maintained endogamy be it at tribal, state or merchant levels as in the case of Adab or other courtly/network cultures. It did not hinder social progress, negotiation or interaction as modern ideologies suggest.

You should make precise points if you expect discussion not long posts or series of tweets with insanely long youtube or long articles videos;

Nicolas Dirk’s book emphasises “recent Social construction” – that is not true for most of the said “Jatis”; – Its not explicit but implied which is up to reader’s interpretation – thats what the author seems to have done (JSD);

That is palpably false;

Quoting Razib khan

“But the last 15 years of genetics and genomics has confirmed in fact that broadly speaking varna maps onto real patterns which are at least 2,000 years ago. That is, genetic affinities and relatedness exist on a spectrum that maps very well onto varna spectrum, beyond Brahmins and Dalits.”

So you are copying responses from twitter {Iona Italia} – You should make precise points…….

—————————————————-

Here is short argument –

Endogamy is the result of many things Spatiality, Language, Trade & royal networks etc. Thus can not be taken alone as proof of ‘Caste’.

Pre-modern world & it’s modes of interaction suggest that endogamy & these networks developed in parallel i.e. endogamy was retained by most communities before industrial revolution all over the world {though degrees differ depending upon region, regional natural changes etc.}

So endogamy was seen as a barrier only when new modes of interactions became available like Schools, industries, printing etc. & class endogamy is still a big issue even in Developed world which are observable in marriage & divorce rates.

I saw that interaction and agreed with it.

Never the less the point stands;

//

{though degrees differ depending upon region, regional natural changes etc.}

//

Its the differing degrees that we talk about when we talk about endogamy – and what caused it to be so stark – common sense explanations dont work to explain to it – you can continue thinking so if you wish – but I DONT – and MANY others don’t.

Also the social identities may have been conditional among Sudra and Vaisya Varnas – Brahmins, “Avaranas” and even Kshatriyas had considerable social consciousness of what their particular Varna encompassed and what their Jatis contain.

So later social construction doesn’t work even as a self identifier ;

Having said that imposition of priesthood on brahmins (as identified by JSD) is something i stand with.

If differing degrees is your argument then you can’t overlook when & where what kind of specialities emerged since work specialization was linked to trade networks, merchants & states etc.

Since no homogenizing force emerged in subcontinent {theologically or monarchically} because Mandala Kingship emerged as common mode of regional control the regions even when competed via same/similar terminology or social milieu they did not lose their regional connect hence you see it being articulated in academia as Sanskrit Vs Vernacular which is again getting revised from Vs to dialogue.

// common sense explanations dont work to explain to it //

They do but if you are willing to look at the past through different lenses instead of modern lenses.

Consider the case of names of communities & what does those names referred to – {3 differential axis}

1. Spatial position – Trushkas, Yavanas, Romaka etc.

2. Professions – Shrenis

3. Language & other cultural differences

What do we find regarding endogamy {though i can’t vouch for their methodology as i am not a geneticist} –

https://phys.org/news/2021-01-ties-india-genetic-diversity-language.html

As thought experiment, consider this –

What people interpret as egalitarian ancient Indian society might have remained violent tribalistic society just like many other parts of that period without Hinduism & though it seems to have supported social differentiation yet it may have allowed for non-violent negotiations through ritual means & by proving an alternative to prior violent tribal ways.

https://www.academia.edu/51075928/Renegotiating_ritual_identities_2019_Tantric_Communities_in_Context_eds_Nina_Mirnig_Marion_Rastelli_and_Vincent_Eltschinger_Vienna_Austrian_Academy_of_Sciences_Press_107_135

https://www.academia.edu/43971455/Dignity_and_Status_in_Ancient_and_Medieval_India

// Also the social identities may have been conditional among Sudra and Vaisya Varnas – Brahmins, “Avaranas” and even Kshatriyas had considerable social consciousness of what their particular Varna encompassed and what their Jatis contain. //

If these identities were so fixed then why did communities showed dissonance during Caste census {one of the central arguments of N. Dirks book} ?

Following video highlights how 18th century Rajasthan royal documents show shifting usage of claim making & differentiation terminologies –

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KNJyjgG-bN0

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/once-dalits-were-landowners-vellalas-slaves/article18405606.ece

What happened to social consciousness here in 15th century ?

Lastly liberals are able to reinterpret same sources they claimed to be Brahmanical & nonredeemable which suggests that they were preferring certain interpretation over other due to their ideological preferences –

https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/dharma-and-caste-mahabharata

Social consciousness does not seem to follow through esp. if one looks deeper into material sources.

It is completely logical that jati genetics are the result of a millennia’s stratification and endogamy – or maybe even longer. But extending jati conclusions to varna is a bit of a stretch. We do not have a complete sample of varna populations from even 100 years ago.

How do we know that the jati groups with the highest Steppes admixture were not at the bottom of the Varna pyramid a 1000 years ago? Is it possible that the Indian system allowed groups at the bottom to climb to the top while the top moved to the bottom? A slow moving torus in spacetime……

If we apply Popper’s criteria of non-falsification, then the claim of varna rigidity based upon genetics becomes untenable.

This is the same problem that confronts cosmologists. Every speck of data we have collected about the visible universe is only worth 50 years. And this 50 years is a moving target……the further the observation is from, the older is it and has no present value. If the universe was a house 200 foot wide, 200 foot long and 200 foot tall – the gap we see into approximates a window 1 micron by 1 micron in size. And we are concluding based on that windowś observations!

Have we sampled a Brahmin from 500 years ago? Or a Kshatriya from 700 years ago? Or a Vaishya from 1000 years ago? Until this possibility materializes, Varna conclusions aren’t tenable.

Ugra, I think you have too much of an eye for mystery novels of Poirot Sherlock kind.

Generally the most parsimonious explanation is the true one. You like to spin fanciful theories which are possible yet highly improbable

Be it in this case / or ur take on Steppe Slave theory – or JR redating of Mauryan empire.

As this particular theory comes out of ancient history into medieval and modern times – your speculations are improbable than wrt ancient history.

Ofcourse it’s possible ; but not all possible things happen

I think the north will provide the brawn, while the south ( sampath, sai deepak) provides the brain , for hindutva of next generation.

Not surprised. That’s how it has always been in other areas too.

Your whole shtick was that the south wasn’t Hindu enough, no? At least compared to the north? Are you changing your tune now?

(Haven’t been around this forum much recently.)

Well that still remains my thing.

South Hindu-ness is skin-deep. So the top is ritualistic and ‘trad’. Unlike the North (where Hindu-ness is more fertile with OBC and dalits pitching in, so more earthy and crass) , South can provide the ‘polished’ validation for Hindutva. Anyways the South Hindu-dom has little political impact/street power, so might as well help out in this intellectual pursuit.

I think attributing the Enlightenment to Protestantism per se is a mistake. I find arguments drawing lines from Calvinist theological precepts to the kind of liberal individualism that was among the hallmarks of the Enlightenment (apart from the rationalism) to be a big stretch. Nassim Taleb thinks religion is downstream of culture (see https://medium.com/incerto/religion-violence-tolerance-progress-nothing-to-do-with-theology-a31f351c729e) and I think he’s on to something here.

More salient to the emergence of the Enlightenment, I believe, was the stalemate between Protestants and Catholics (Thirty Years War and the rest), forcing them to make peace with the idea of co-existence and thereby embarking on the quest of trying to find meaning outside of religion. If the Protestants had won outright, they may have degenerated into something akin to Islam (albeit with a Germanic flavor) IMHO.

I still believe, as a classical liberal, that Enlightenment values are universal values that were first stumbled upon in the West, and it’s idiotic to try and chart a path for India that willfully rejects these values. Just because the British liberal imperialists (the Mills, Macaulay, etc.) were hypocrites in their treatment of India and Indian culture doesn’t make that value system itself worthless.

Exactly my point!

I don’t think we would end up with something like Islam, since while Germans have shown a remarkable tenacity towards weaponised autism, they have also been very willing to try new ideas, and often explored them to their fanatical ends, before switching on a flash. Islam isn’t very innovative, even if it can be fanatical. That’s a crucial difference.

Otherwise, I agree with you. The enlightenment came from culture and religious expressions are downstream from that. I think using a religious lens is a very typical Indian approach, which makes a lot of sense on the subcontinent but less so in European history (as strange as it might seem, given the intensity of these religious wars at the time).

Ultimately, these ideals were born out of pragmatism. From thereon out, various intellectuals provided the moral edifice to continue and build on them, lest Europe collapse into internecine warfare every other year. (Their success was mixed at best).

we tried liberal democracy for 70 yrs, we are not rich, we don’t even have rule of law and no free speech either . Perhaps Confucian values serve better?, why should we not try that instead?. Can we stop performative pro western arguments here at least and talk about logistics of what it takes to get things done?. Convincing enough number of millions of Indians to take up to classical liberalism requires investment in education that has not been made, and it requires disposition that is not just there in enough number of educators or in any of our political leaders. This is idle dreaming. Perhaps we should aim for being rich, rule of law and leave liberalism to the future generation, right now we are falling between different stools.

Its likely too late, but restoration of monarchs wherever workable post-independence could have been the anchor of legitimacy for good governance/prosperity.

Dont ya think considering the diversity, having monarchs is even worse solution than what we have currently.

I mean we have riots/political mobilization on caste/religious lines when ‘our’ guy is not the PM/CM of a state, and that guy remains just for 5 years. Think of Hyderabad under Nizam today. Or Kashmir with Hari Singh.

we already are following many things which are not ‘liberal’ in the western sense, and may qualify as Confucius thought, such as:

1. respect for elders and taking care of them.

2. respect for gradation (taratamya)

3. respect for authority.

in the public space, the behaviour is hardly ‘liberal’.

the kind of noisy democracy we have cannot be wished away.

Why 2 of my responses did not show up ? That’s the reason i stopped responding on BP as responses do not get through as per the convenience of the moderators.

Do not be thin skinned;

Any long comments with links get into spam folder by default ;

None of the moderates have time and energy to keep checking spam for your and some other comments – though when someone notices they must be “unspamming” it (as i have done).

It happens every now and then for handles who post “links” – its done automatically by Akismet I presume.

if you want to avoid this – post shorter comments without hyperlinks links (you can help user with Youtube/Google keywords)

Thank you for finding my responses & unspamming them. I am grateful to you for doing it, thank you.

Only reason i use ‘hyperlinks’ because anyone can then check the sources, scholarly works etc. before criticizing me for conjuring up unsubstantiated & absurd theories and come up with a much more nuanced takes for their own arguments.

For e.g. Within last few days i come across a paper & few videos which throw spanners into the academically dominant Brahmanical Vs Buddhist narrative.

https://www.csds.in/religious_endowments_in_first_millennium_india_lecture_by_timothy_lubi

Note – Do watch this video as how Brahmin Profession by merit Vs Brahmin by birth got conflated at 58min. mark.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbURhlb9zaA

https://www.academia.edu/63732680/Early_Buddhism_and_its_Relation_to_Brahmanism_A_Comparative_and_Doctrinal_Investigation

I am not hoping to change anyone’s mind regarding existing Buddhism Vs Hindu narrative but rather i hope that people from different camps can come together to make their arguments more nuanced & up to date to the kinds of resources available now.

Should i cut these sources to argue as per my preferred positions or is allowing people the access to sources to make their own interpretations is a better choice – I leave it to the wisdom of BP forum & it’s users.

Well I don’t think I would disagree with you there – do I –

I also think the Brahmin Buddhist distinction is way overplayed. As JSD points out largely due to initial study from Protestant FW. I agree broadly.

I just don’t agree with ur speculations of Varna Jati though I don’t dismiss them do I ? But I just don’t agree for find it logical.

With ur comments maybe I have would again urge you to write something with linearity – Vedic times – Janapada – CE etc etc

// With ur comments maybe I have would again urge you to write something with linearity – Vedic times – Janapada – CE etc etc //

Only reason i avoid writing in this manner because it requires one to take make even greater assumptions on date of ‘religious’ texts, interpretations etc. at the expense of other sources.

It makes the whole exercise even more theoretical & thus even more unsubstantiated than my current method of trying to understand the modes of distinction of differentiation under different periods, contexts, settings & human society’s evolution.

// I just don’t agree with ur speculations of Varna Jati though I don’t dismiss them do I ? But I just don’t agree for find it logical. //

Why do you not find them logical, plz. elaborate & what about recent Genetic study highlighting link between endogamy & Language in subcontinent, do you dismiss it to ?

Refer

(Quote) … which is not just an exaggeration but an objectively falsifiable statement.

” In some cases diseases, such as smallpox and the plague, were introduced with the knowledge that the indigenous community was not immune to them.

Kindle location 1054″ (Unquote)

How does one conclude that it is an exaggeration ? and/or that it is objectively false ? (Falsifiable, ok, but that need not necessarily mean false, as I understand.

However, given the context, I assume it means false).

Can this (below) be considered as evidence of the statement ?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Fort_Pitt#Biological_warfare

Three books are mentioned as references, perhaps they cannot be dismissed out of hand. I have not read them, btw.

Again, from Wikipedia : ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Population_history_of_Indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas#Biological_warfare )

(Quote) During the Seven Years’ War, British militia took blankets from their smallpox hospital and gave them as gifts to two neutral Lenape Indian dignitaries during a peace settlement negotiation, according to the entry in the Captain’s ledger, “To convey the Smallpox to the Indians”.[44][52][53] (Unquote)

44 = The Tainted Gift; Barbara Alice Mann; ABC-CLIO; 2009; pp. 1–18,

52 = Pontiac and the Indian Uprising; Peckham, Howard H.; University of Chicago Press; 1947; pp. 170, 226–27.

53 = Pontiac and the Indian Uprising; Peckham, Howard H.; University of Chicago Press; 1947; pp. 170, 226–27

Same as above, perhaps these (additional) three books cannot be dismissed out of hand. I have not read them, btw.

falsification not about spread of diseases or even deliberate spread of diseases – but knowing that natives werent Immune to them; in time when germ theory – immunity was unknown

“… but knowing that natives werent Immune to them; in time when germ theory – immunity was unknown ”

The questions that arise are :

(A) Is a knowledge of the germ theory necessary for deliberately causing the spread of disease ?

And

(B) Did the person(s)/organization responsible for spreading disease know that the target population lacked immunity ?

Coming to (A) Is a knowledge of the germ theory necessary for deliberately causing the spread of disease ?

No, knowledge of germ theory is not necessary to wage biological warfare, it would appear, given the following : –

(Quote) “ … The earliest documented incident of the intention to use biological weapons is recorded in Hittite texts of 1500–1200 BCE, in which victims of tularemia were driven into enemy lands, causing an epidemic.[13]

The Assyrians poisoned enemy wells with the fungus ergot, though with unknown results. Scythian archers dipped their arrows and Roman soldiers their swords into excrements and cadavers – victims were commonly infected by tetanus as result.[14] In 1346, the bodies of Mongol warriors of the Golden Horde who had died of plague were thrown over the walls of the besieged Crimean city of Kaffa … ” .

Link : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biological_warfare#Antiquity_and_Middle_Ages

Coming to (B) Did the person(s)/organization responsible for spreading disease know that the target population lacked immunity ?

(Quote) “The Spanish Franciscan Motolinia left this description: “As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease…they died in heaps, like bedbugs. In many places it happened that everyone in a house died and, as it was impossible to bury the great number of dead, they pulled down the houses over them so that their homes become their tombs.”[48] (Unquote)

Link : – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_smallpox#Epidemics_in_the_Americas

48 = “ Quoted in Tzvetan Todorov, The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other (1999:136). ”

There seems to be some error (perhaps something lost in translation) in the quote attributed to Motolina above, as the remedy to small pox (the disease referred to) was not known until much later. It may mean something which was assumed to be a remedy, as variolation is said to have been known in Europe only in the seventeen hundreds, whereas the quote (of Motolina, above) refers to the period around 1520 CE.

Still, something to think about, in my opinion.

Not pursuing this further.

I get that – maybe my criticism could be worded better;

Maybe i need to accept some of my pointed criticism is unfounded.

But the lack of references or explanation of position with some more supporting examples – is missing; and connecting the dotes which you have done here are assumed to be self evident –

My dear sir, we are not confucian , suggest you to read the analects from the wise master. Do not presume to know what that master has to say without reading the work of the master. It is said, “the one who read analects is not the same as before or he is lying and has not read it”.