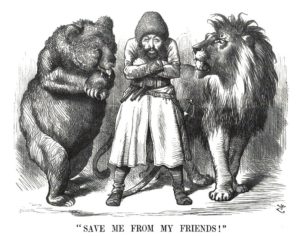

Galwan Valley, Pangong Lake, Karakoram Pass, Doklam Plateau, Mishmi Hills. These obscure geographical features and landmarks in the high Himalayas separating India from China have suddenly made their way back into the public consciousness. The catalyst this time is the increased friction between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of India. I use the phrases “way back” and “this time” deliberately. To scholars and enthusiasts of the Great Game, these names and the surrounding context are eerily familiar: shadow boxing between an ascendant, assertive superpower (Tsarist Russia) trying to throw its weight around in its immediate neighbourhood and an ostensibly weaker but rising middling power (British India) trying to protect its interest in its backyard.

The original Great Game, which played out over the course of the nineteenth century between the British Indian and Russian Empires in South and Central Asia, had all the characteristics of a bestselling novel, filled with action, adventure and intrigue. It also had its set of glamorous characters: Sir Alexander ‘Sikunder’ Burnes- the famous British spy with oodles of charm and dashing good looks to boot- was the James Bond of his era. He was matched on the Russian side by Captain Yan Vitkevich, the enigmatic Polish-Lithuanian orientalist and explorer. Mercifully, there was very little by way of direct bloodshed between the principal protagonists, although things did come close to getting out of hand on a few occasions. No wonder the Russians evocatively called the contest “The Tournament of Shadows”. It was compelling drama and the public- in Britain, India, Russia and beyond- lapped it up. The romance and zeitgeist of the times was captured by the great Victorian author Rudyard Kipling in his famous novel, Kim.

It is said that history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. As India and China metaphorically battle it out in old familiar haunts from Gilgit to Tawang, journalists and scholars are already labelling the contest the “New Great Game”. These are just the throes of a new struggle for access, control and domination of South and Central Asia- one that is likely to go on for a while and provide us with its own epics, fables and heroes. As analysts and commentators look forward to the New Great Game, it is also worth turning our gaze backward, to both seek inspiration and draw lessons from the history of the old Great Game.

A lot of the literature on the Great Game is from a Western- predominantly British- perspective. I have published a long form historical essay on Medium which seeks to examine the era from an Indian perspective- focusing on the Pundits- a remarkable set of Indian spies, explorers and scholars whose significant achievements and contributions have sadly been largely forgotten, including in their own homeland. The essay examines their role and legacy through the lives of three Pundits- Mohan Lal Kashmiri, Nain Singh Rawat and Sarat Chandra Das- spy, explorer and scholar respectively- who epitomised the spirit of their cohort.

The Great Game may feel like ancient history in 2020, but there is a sense of déjà vu. The actors may be different, but the underlying geopolitical tensions feel similar. A bout of frenetic road construction, bridge building and tunnelling by both China and India, aided by cutting-edge engineering has led to the Great Wall of the Himalayas- that eternal barrier separating India from China- appear shakier than ever.

Yet geography still matters. The sheer ruggedness and remoteness of the terrain requires physical patrolling, as was evident in the Galwan Valley at the eastern edge of Ladakh / western edge of Aksai Chin (literally “white desert”) earlier this year, where Indian and Chinese troops engaged in fatal hand-to-hand combat that reportedly resulted in the deaths of over 40 soldiers. This barren, desolate area at a height of over 17,000 feet, right at the intersection of Xinjiang, Ladakh and Tibet is old hunting ground for Great Game enthusiasts. By a twist of fate, even the name Galwan Valley- an eponym of the Ladakhi Pundit Ghulam Rasool Galwan- owes its origins to the Great Game.

The human element- both in terms of knowledge of the terrain, as well as a deep and intimate understanding of the cultures- would be critical in order to succeed in the New Great Game. India would need a new generation of spies, explorers and scholars to follow in the footsteps of Mohan Lal Kashmiri, Nain Singh Rawat and Sarat Chandra Das.

It is tragic that the exploits and feats of the Pundits have been largely forgotten in the land of their birth. Nain Singh Rawat is perhaps the most remembered, largely due to the institutional memory of the Survey of India. The other two, like countless others besides them, are largely forgotten. There are several reasons for this. The British did give some recognition- not as much as Europeans who achieved even half as much- but still better than nothing- while they ruled India. Since then, British accounts have largely focused on their own heroes and personalities, with the Pundits playing ancillary roles. The nationalist sentiment in independent India tends to taint anyone who worked with the British colonial authorities as “collaborators”, regardless of their individual merits or qualities. The only ones glorified as heroes are the freedom fighters who fought against colonial rule.

Such attitudes are a mistake. While the freedom fighters deserve due admiration and respect, the Pundits are equally worthy of admiration. Their love for adventure and thirst of knowledge can kindle a spark in a new generation as it gears up for the New Great Game. They are heroes who deserve to be remembered.

I read almost a dozen books and several articles to write the essay. It’s got interesting maps, images and trivia. It doesn’t fit very well with the Brown Pundits blog format, but if you are interested in long form history or just a good story, read the whole thing here. I would also be interested in Brown Pundit readers comments or feedback on the essay.

Interesting topic, I will read the whole story. You will maybe interested to know that a Serbian spy was a ‘prototype’ for James Bond.

https://www.bbc.com/reel/video/p086f8jn/the-playboy-serbian-spy-who-inspired-james-bond

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/mar/22/from-the-archive-the-real-james-bond-1973-dusko-popov-ian-fleming

Countries in Asia would have been much better had they been drawn according to sphere of influence – for e.g. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan (and Xinjiang) would have been better to be part of a country for Turkmens.

Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan as parts of Iran/Persia.

Bangladesh and places like Barak valley, Assam Valley, West Bengal, Bihar – form a single continuum.

Naga areas in both India and Myanmar are much more similar, same with Chin state in Myanmar and Mizoram.

Imperialism and modern nation states really screwed up a lot of things.

Who was gonna draw the borders, if not the violent imperialists? The end of Ottoman Empire marked the end of Turkic Global Power, they were the only ones who could’ve laid the groundwork for a modern Pan-Turkic State and they ended up being the losers of WW1 instead.

> Who was gonna draw the borders, if not the violent imperialists?

The local empire could’ve done that. For e.g.: the Persians, Marathas/Sikhs etc.

I read the full piece on Medium. These men were cartographers, anthropologists, military recce-men – all rolled into one!

@Ugra- indeed. It’s remarkable how little the average Indian knows about them. Nain Singh is a partial exception due to the Survey of India’s institutional memory. My theory is they are not “convenient heroes” for anybody. The nationalist narrative views them as collaborators, as described above. The Marxists (now metamorphosed into the woke left) views them as upper caste Hindu men who worked with White men- so not interesting for them. Their tastes are also probably too international and eclectic to inspire the Hindutvites. So they are orphans in India with no faction particularly keen to appropriate their legacy.

The actions of the Nehruvian establishment served to de-emphasize the heroes of the previous tenancy – the British. While the actions of the Hindutva House is to belittle Nehruvian idols. This is a cycle.

These people fell between the cracks. Perhaps their Age is yet to arrive.