The film Panipat is on Netflix, and I watched a bit of mostly for anthropological reasons. It seems a typical melodramatic Bollywood gloss on this period, and I found the depiction of Ahmad Shah Durrani rather amusing.

But it brought to mind a broader issue that I’ve been reflecting on over the past few years: the re-pivoting of Indian historical imagination around the Maratha moment. Most recently my thoughts have been sharpened by the goings-on in the United States, as we reevaluate our own historical figures and events. History is what it is, but the interpretation is multi-layered, and the process of analysis is subject to an infinite chain of point and counterpoint.

For example, Ulysses S. Grant has been rehabilitated because broadly on the questions of racial justice he was on the “right side of history,” though ultimately his efforts failed. This, after a period in the 20th-century when Southern historians slandered his character and competence in a clever trick of defeating him long after his death through control of historical memory.

And yet, if you talk to a Native American their view of Grant is far less positive. This is due to the fact that Grant participated in and executed the American government’s wars against Indian tribes.

The final verdict on Grant and his legacy depends on where you stand. The elements of history which lead up to this judgment though are far more solid. The terminus of the analysis is conditional on the analyst, but the facts themselves are invariant.

So how should we view the Marathas and the Mughals? When I wrote Haunted by History I alluded to general issues I’ve noticed in Indians in relation to their past. I have read enough history to be aware of the Marathas as a factual matter. But my conscious understanding of what they meant to Indians, and what they could have been, was stimulated by the arguments of a Hindu nationalist friend of mine.

In the 19th and 20th century various nationalist movements rose up which recaptured the political system from cosmopolitan and/or alien elites. The Chinese took back their state from the Manchus. Across Europe, ethnic groups such as the Lithuanians and Hungarians, submerged, sublimated, or subordinated, rose up and asserted their national identity. Lithuanians and Hungarians, to give two examples, had great histories as nations in the past, but by the early modern period, their elites had become subordinated and assimilated. The Lithuanian nobility became totally Polonized after the Union of Lubin. The rise of Habsburgs, and the fall of the Hungarians to the Ottomans, resulted in a Magyar nation which was under German and Turkish domination for centuries. The Dual Monarchy period after 1868 allowed the Hungarian nobility more freedom and status, though ironically they continued to oppress and subordinate the ethnic minorities under their hegemony in the eastern part of Austria-Hungary.

The emergence of these new identities entailed a reinterpretation of the valence of historical events.

Before we get to that, let’s consider the Marathas, of all castes and persuasions. The debates I have seen often end up at two antipodes. On the one hand, the Marathas are depicted as proto-Hindu nationalists, defending themselves against Muslim oppressors, and giving their swords in the service of the broader pan-ethnic Hindu Rashtra. The contrasting position is that the Marathas were motivated by more prosaic concerns, and their Hinduism was a secondary or ancillary element to their identity. In fact, one might problematize what “Hindu” even meant in the 17th and 18th centuries. That is, they didn’t have a “Hindu identity,” but had a Maratha identity, and Maratha religious practices and beliefs.

Both of these views are I think wrong-headed in understanding this period and these people. Humans are complex, and not cartoons. Someone like Shijavi may have reimagined who he was, what he could become, over his lifetime. In the beginning, he fought to survive. By the end, he fought to conquer.

Certainly, it seems probable, to give a different example, that Constantine, the first Christian Roman Emperor, reconceptualized his relationship to his new faith over the decades and also reimagined what it might mean for Rome. This is a different reading than that of those who assert that Constantine was never really a Christian because in the early years of his acceptance of the new faith he seems to still have nodded to aspects of the Solar cult which he was once a devotee, or of those who assert that he was a zealous Christian as they would understand it after he issued the Edict of Milan.

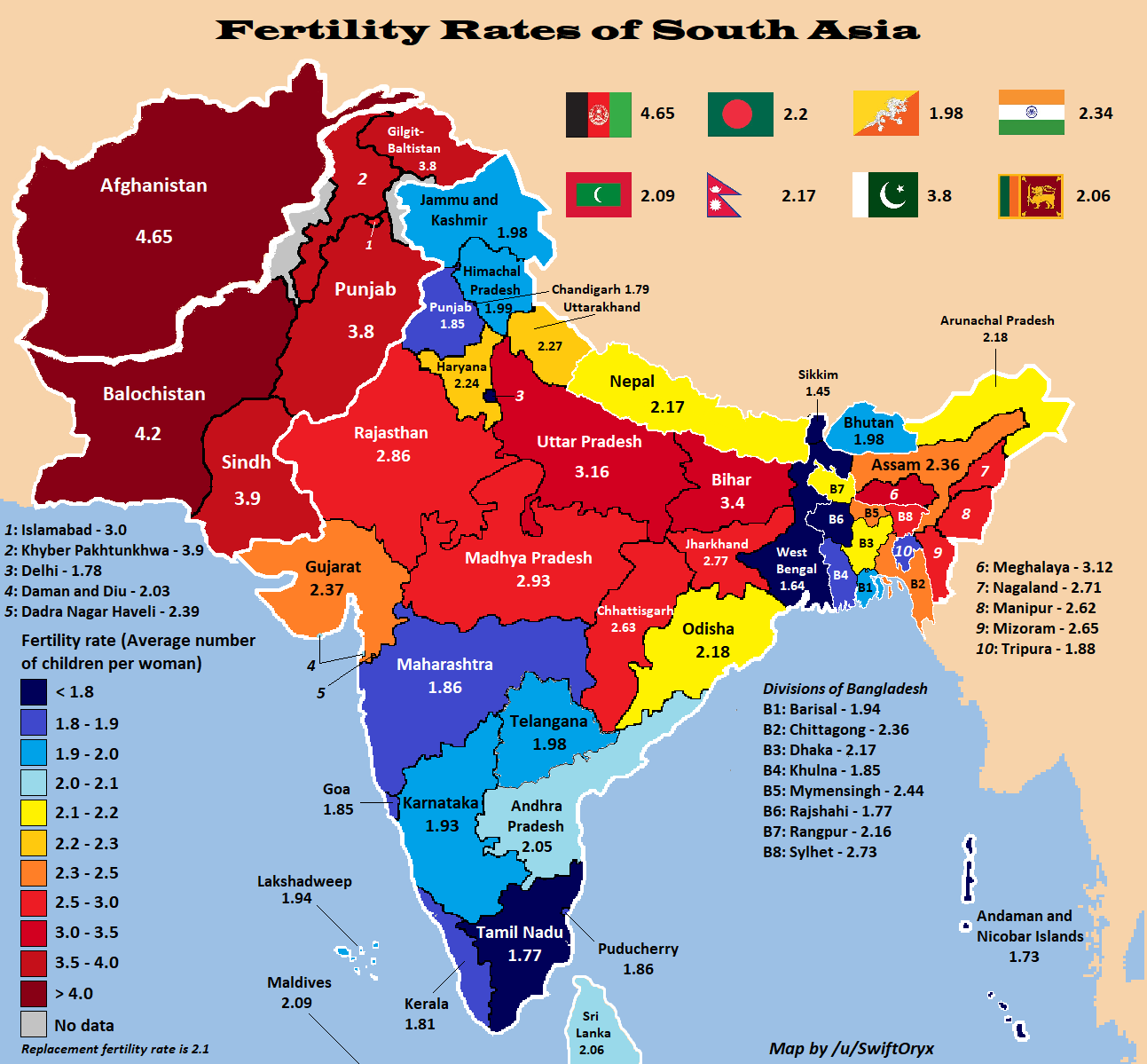

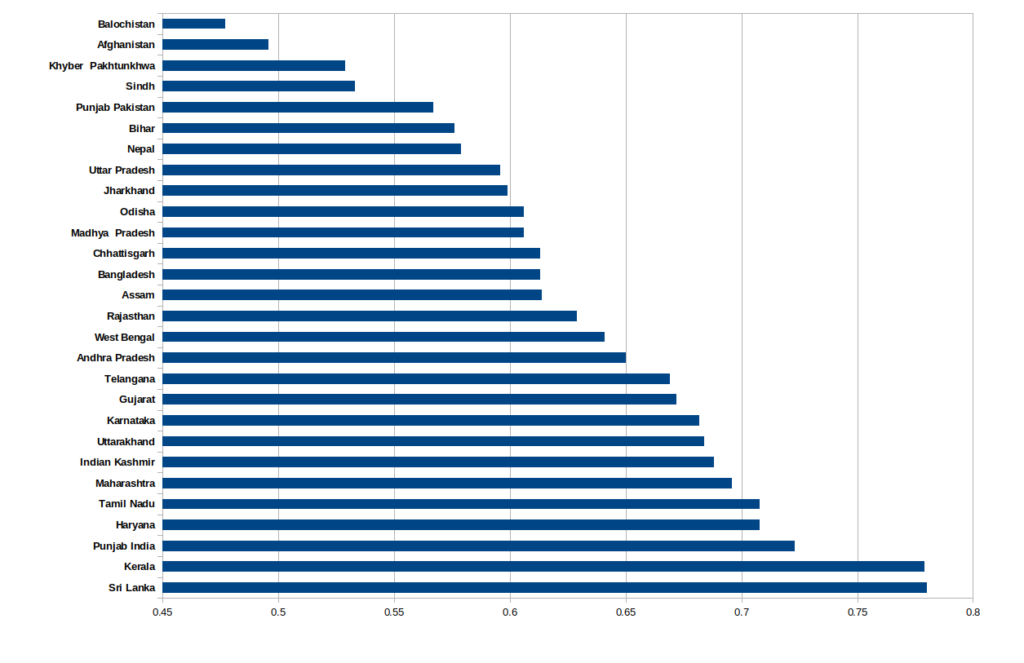

Where does this leave us? I have spoken earlier of the fact that to be frank, many people from Uttar Pradesh who are Hindu seem somewhat “broken.” Perhaps I should use a different word, as what I’m trying to get at is ineffable. But I believe that hundreds of years of continuous Turco-Muslim domination, and the historical predations upon their sacred geography, has left an imprint. Their land was the heart of the Mughal Empire, the shining exemplar of Turco-Muslim civilization. Though the Indian religion and self-identity maintained itself in a resilient fashion, it was subaltern. Though never sublimated as the Lithuanians were, it was subordinated.

Mount Rushmore means a very different thing to Native Americans than it does to white Americans. To many Hindus from the Gangetic plain, the apogee of the Mughals means something different than it does to Urdu-speaking Muslims. One man’s glory is another man’s shame. One man’s seduction is another man’s cuckoldry.

Which brings me to the “Maratha mindset.” What do I mean by this? I mean a self-assured, self-confident attitude. The sense that the arc of history bends toward the Dharma. The Maratha project failed in the end, but its ultimate failure was due to the reality of European hegemony and the rise of white supremacy across the globe. It seems possible in an alternative history where European domination occurred later, or in an incomplete fashion, the Maratha polities would have served as the ultimate basis for what became the Indian nation-state. This does not mean that Maratha would be the language of the Indian nation-state, or that the culture of the northwest Deccan would be hegemonic. An analogy here might be the role that elites from the Chūgoku region of western Japan played in driving modernization in the Meiji period, before eventually ceding ground to the resurgent Kanto region around Tokyo. Chūgoku was the nucleus, but only the beginning, the “starter.” The final product is always richer and more multi-faceted.

The moral of this post is that the Hindus of the Gangetic plain resisted Islamicization through a process of fracturing into localities, with a broader civilizational identity. But the resistance and centuries of Mughal domination crushed cross-regional asabiya, which is necessary for nation-building. Obviously the nation is built, and Uttar Pradesh in particular is politically central. But the psychology of the Hindus of this region has to move from negation, reaction, to positive action. They need to shake off their history and move forward into the future. They need to adopt the Maratha mindset.