There is this belief that is held by many that the high steppe ancestry in Jats is based somehow on some latter steppe migrations into the region. But obviously there is no proof for it. The association of Jats with some Central Asian migrants and more specifically the Indo-Scythians is a myth created in the 19th century and does not have any foundation whatsoever. However some people hold onto this myth and feel a vague sense of pride in it.

Nevertheless, there is a very easy and straightforward explanation for why the Jats have such a high steppe ancestry. Here are a few things to keep in mind.

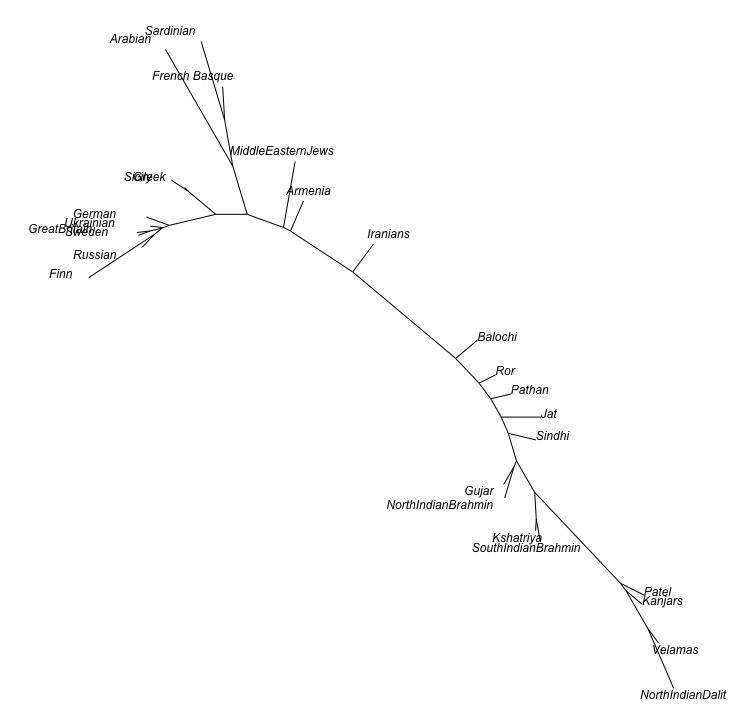

- The Haryanvi and Western UP Jats have apparently the highest ‘steppe’ ancestry among South Asians.

- This ‘steppe’ ancestry is associated with the spread of IE langauges in South Asia with Brahmins and Kshatriyas in any region having a higher share of this ancestry than the other groups within that region.

- The Vedic homeland was in Haryana and Western UP, the Kuru heartland from where the Vedic cultural influence spread into interior South Asia.

Let me quote Michael Witzel which is an avowed AMT proponent,

Kuruksetra, the sacred land of Manu where even the gods perform their sacrifices, is the area between the two small rivers Sarsuti and Chautang, situated about a hundred miles north-west of Delhi. It is here that the Mahabharata battle took place. Why has Kuruksetra been regarded so highly ever since the early Vedic period?…

…It can be said that the Bharata/Kaurava/Pariks.ita dynasty of the Kurus sucessfully carried out and institutionalized a large scale re-organization of the old Rgvedic society. Many aspects of the new ritual, of the learned speech, of the texts and their formation reflect the wish of the royal Kuru lineage and their Brahmins to be more archaic than much of the texts and rites they inherited. In this fashion, the new Pariks.ita kings of the Kurus betray themselves as typical newcomers and upstarts who wanted to enhance their position in society through the well-known process of “Sanskritization.” In fact, to use this modern term out of its usual context, the establishment of the Kuru realm was accompanied by the First Sanskritization. Incipient state formation can only be aided if it is not combined with the overthrow of all inherited institutions, rituals, customs, and beliefs. The process is much more successful if one rather tries to bend them to one’s goals or tries to introduce smaller or larger modifications resulting in a totally new set-up. The new orthopraxy (and its accompanying belief system, “Kuru orthodoxy”) quickly expanded all over Northern India, and subsequently, across the Vindhya, to South India and later to S.E. Asia, up to Bali.

This procedure is visible in the Bharata/Kaurava dynasty’s large scale collection of older and more recent religious texts: In all aspects of ritual, language and text collection, these texts tend to be more archaic than much of the inherited older texts and rites. On the other hand, the new dynasty was effective in re-shaping society and its structure by stratification into the four classes (varna), with an internal opposition between ¯arya and ´sudra which effectively camouflaged the really existing social conflict between brahma-ksatra and the rest, the vaisya and ´sudra; further, the Bharata/Pariksita dynasty was successful in reorganizing much of the traditional ritual and the texts concerned with it. (It must not be forgotten that public ritual included many of the functions of our modern administration, providing exchanges of goods, forging unity and underlining the power of the elite.)

The small tribal chieftainships of the R°gvedic period with their shifting alliances and their history of constant warfare, though often not more than cattle rustling expeditions, were united in the single “large chiefdom” of the Kuru realm. With some justification, we may now call the great chief (raja) of the Kurus “the Kuru king”. His power no longer depended simply on ritual relationships such as exchange of goods (vidatha) but on the extraction of tribute (bali) from an increasingly suppressed third estate (vi´s) and from dependent subtribes and weak neighbors; this was often camouflaged as ritual tribute, such as in the a´svamedha.

In view of the data presented in this paper, we are, I believe, entitled to call the Kuru realm the first state in India.

Witzel also states elsewhere in the text,

The famous Videgha Mathava legend of ´SB 1.4.1.10 sqq. tells the story of the “civilization process of the East” in terms of its Brahmanical authors, and not, as usally termed, as the tale of “the Aryan move eastwards.For it is not only Videgha Mathava, a king living on the Sarasvatı, but also his priest Gotama Rahugana who move towards the east. Not only is the starting point of this “expedition” the holy land of Kuruksetra; the royal priest, Gotama Rahugana, is a well known poet of R°gvedic poems as well, and thus, completely anachronistic. Further, the story expressively mentions the role of Agni Vai´svanara, the ritual fire, in making the marshy country of the East arable and acceptable for Brahmins. All of this points to Sanskritization or rather, Brahmanization) and Ks.atriyazation rather than to military expansion.

The M¯athavas, about whom nothing is known outside the ´SB, may be identical with the m´athai of Megasthenes (c. 300 B.C.), who places them East of the Paz´alai (Pancala), at the confluence of the Erennesis (Son) with the Ganges. The movement of some clans, with their king Videgha and his Purohita, eastwards from the River Sarasvatı in Kuruksetra towards Bihar thus represents the ‘ritual occupation’ of Kosala(-Videha) by the bearers of orthoprax (and orthodox) Kuru culture, but it does not represent an account of the first settlement of the East by Indo-Aryan speaking tribes which must have taken place much earlier as the (still scanty) materials of archaeology indeed indicate.

According to Talageri,

…the geographical area of the Rigveda extends from westernmost U.P. and adjoining parts of Uttarakhand in the east to southern and eastern Afghanistan in the west. Strictly speaking, in present-day political-geographical terms, this includes the whole of northern Pakistan, adjoining areas of southern and eastern Afghanistan, but, within present-day India, only the state of Haryana with adjoining peripheral areas of western U.P and Uttarakhand..

…The descriptions in the Puranas about the locations of the Five Aila tribes in northern India clearly place the Purus as the inhabitants of the Central Area (Haryana and adjacent areas of western U.P.), the Anus to their North (Kashmir, etc.), the Druhyus to their West (present-day northern Pakistan), and the Yadus and Turvasus to their South-West (Rajasthan, Gujarat, western M.P.) and South-East (eastern M.P. and Chhattisgarh?) respectively. The Solar race of the Ikshvakus are placed to their East (eastern U.P, northern Bihar). This clearly shows that the Purus were the inhabitants of the core Rigvedic area of the Oldest Books (6, 3, 7): Haryana and adjacent areas, and they, and in particular their sub-tribe the Bharatas, were the “Vedic Aryans”. Their neighboring tribes and people in all directions were also other non-Vedic (i.e. non-Puru) but “Aryan” or Indo-European language speaking tribes. The Puru expansions described in the Puranas explain all the known historical phenomena associated with the “Aryans”: the expansion of Puru kingdoms eastwards explains the phenomenon which Western scholars interpreted as an “Aryan movement from west to east” (the area of the Rigveda extends eastwards to Haryana and westernmost U.P., the area of the Yajurveda covers the whole of U.P., and the area of the Atharvaveda extends eastwards up to Bengal), and their expansion westwards described in the Puranas and the Rigveda explains the migration of Indo-European language speakers from the Anu and Druhyu tribes (whose dialects later developed into the other 11 branches of Indo-European languages) from India..

The evidence is unequivocal. Quite clearly, the Vedic culture spread into the Gangetic plains and later on elsewhere from its central locus of the Kuru realm which was in Haryana and Western UP.

So is it so outrageous that the dominant community living presently in the traditional Vedic heartland from where the Vedic culture, ritual, language and religion is suppossed to have spread across inner South Asia, also has the highest ancestry of the type which is usually today associated with the spread of IE or Indo-Aryan languages and culture in South Asia ?

So why hold onto the unsubstantiated 19th century colonial myths when the evidence is so clear and straightforward ? As Razib has pointed out, a latter steppe admixture into the Jats from groups like Scythians is also difficult to argue because the Jats lack the East Eurasian component which is present in very signficant proportion in steppe groups from Iron Age onwards.

Infact, the close ancestry sharing between the Kalash, Pashtuns, Pamiris and Jats indicates, as I have argued earlier in greater detail, that this shared ancestry with high ‘steppe’ component goes back to the days of Indo-Iranian unity within the northwest of the subcontinent because while Jats are Indo-Aryan and Pashtuns are Iranian speakers, the Kalash are representative of the Nuristani branch which is often taken as the 3rd branch in Indo-Iranian.

One question that is often asked is – why are Jats not at the top of caste heirarchy ?

There is also a good explanation for this. The Indo-Aryan expansion from its Haryana-Western UP heartland is a roughly 4,000 year phenomenon. A lot of water has flown under the bridge since then. Mahapadma Nanda, who established the first major South Asian empire is stated in the Puranas to have destroyed the Kshatriyas, and attained undisputed sovereignty. The Kshatriyas said to have been exterminated by him include Maithalas, Kasheyas, Ikshvakus, Panchalas, Shurasenas, Kurus, Haihayas, Vitihotras, Kalingas, and Ashmakas.

As you can see, the Kshatriyas among the Kurus, along with those of other kingdoms, were already exterminated during the time of Mahapadma Nanda eons ago. So it is no surprise that present day Jats don’t hold any special position in the caste heirarchy.

I end here by taking a detour with the beautiful story of Pururavas, who is the ancestral figure of all Vedic tribes and is most likely an Indo-Iranian ancestor from the remote past. Noticeable aspects of the story include the fact that the place of Kurukshetra, Haryana has a mention in the story as a place of action and that sheep herding appears to have been a feature of this early nascent Indo-Aryan/Indo-Iranian period.

Pururava was a good king who performed many yajnas. He ruled the earth well. Urvashi was a beautiful apsara. Pururava met Urvashi and fell in love with her.

“Please marry me,” he requested.

“I will,” replied Urvashi, “But there is a condition. I love these two sheep and they will always have to stay by bedside. If I ever lose them, I will remain your wife no longer and will return to heaven. Moreover, I shall live only on clarified butter.”

Pururava agreed to these rather strange conditions and the two were married. They lived happily for sixty-four years.

But the gandharvas who were in heaven felt despondent. Heaven seemed to be a dismal place in Urvashi’s absence. They therefore hatched a conspiracy to get her back. On an appropriate occasion, a gandharva named Vishvavasu stole the two sheep. As soon as this happened, Urvashi vanished and returned to heaven.

Pururava pursued Vishvavasu and managed to retrieve the sheep, but by then, Urvashi ahd disappeared. The miserable king searched throughout the world for her. But in vain. Eventually, Pururava came across Urvashi near a pond in Kurukshetra.

“Why have you forsaken me?” asked Pururava. “You are my wife. Come and live with me.”

“I was your wife,” replied Urvashi. “I no longer am, since the condition was violated. However, I agree to spend a day with you.”

When one year had passed, Urvashi returned to Pururava and presented him with the son she had borne him. She spent a day with him and vanished again. This happened several times and, in this fashion, Urvashi bore Pururava six sons. They were named Ayu, Amavasu, Vishvayu, Shatayu, Gatayu and Dridayu.

There is one number which is reported in the piece and aligns with everything I’ve ever seen in the United States of America: 90% of Indian Americans are not lower caste. Of those who are lower caste, whatever that means, I doubt much more than 1% are Dalit. I know this partly because I have a sampling of 300 Indian American genotypes from one of the DTC firms (four parents born in India), and the genetic variation aligns pretty much with the above distribution.

There is one number which is reported in the piece and aligns with everything I’ve ever seen in the United States of America: 90% of Indian Americans are not lower caste. Of those who are lower caste, whatever that means, I doubt much more than 1% are Dalit. I know this partly because I have a sampling of 300 Indian American genotypes from one of the DTC firms (four parents born in India), and the genetic variation aligns pretty much with the above distribution.