Do state capacity and policy really matter when it comes to wealth among regions in South Asia ? Or is prosperity today determined largely by a mixture of geographical and historical factors ? South Asia as a unit is a reasonable region to study because the introduction to modernity in this entire region was mediated by the British Empire.

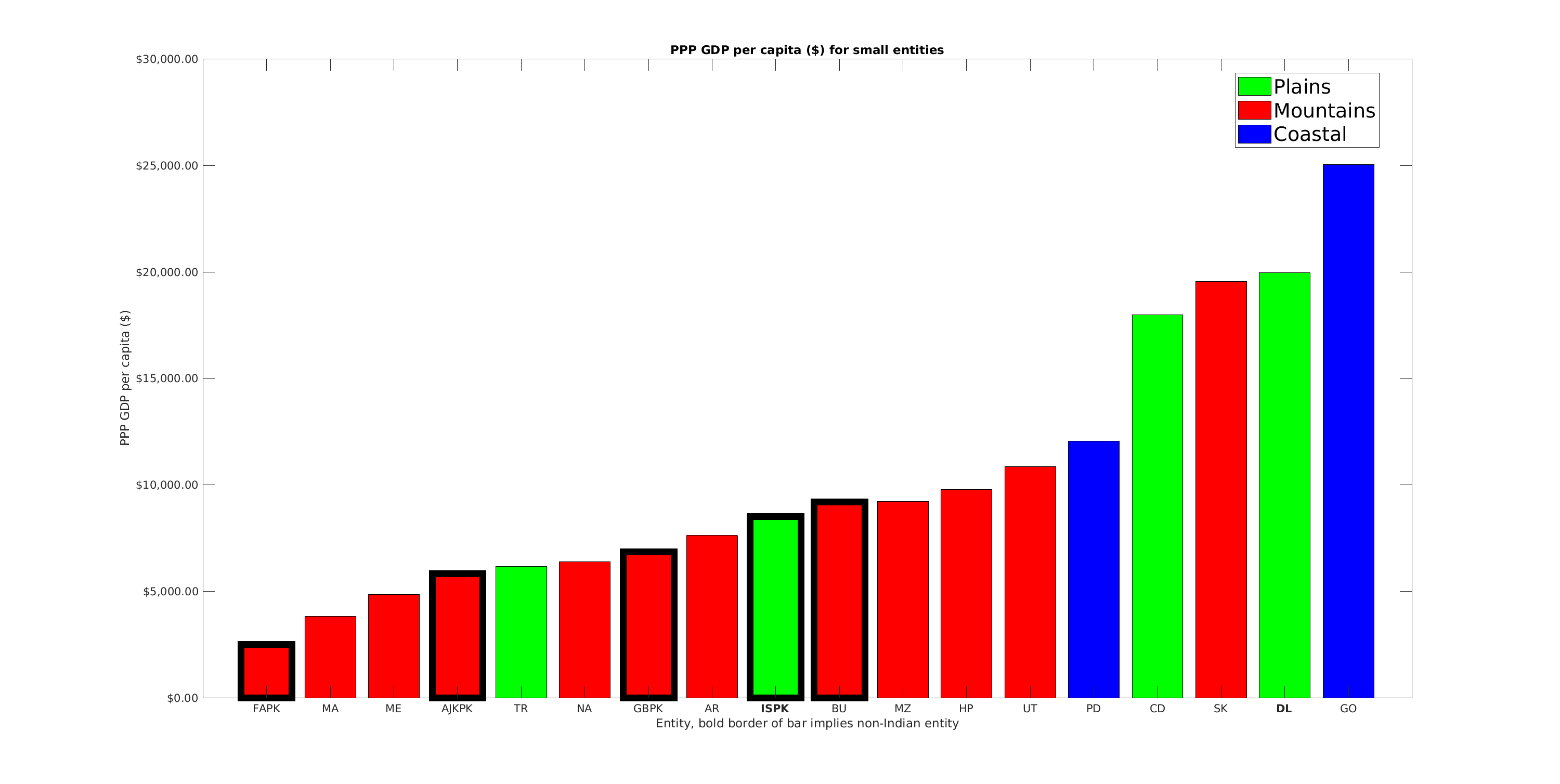

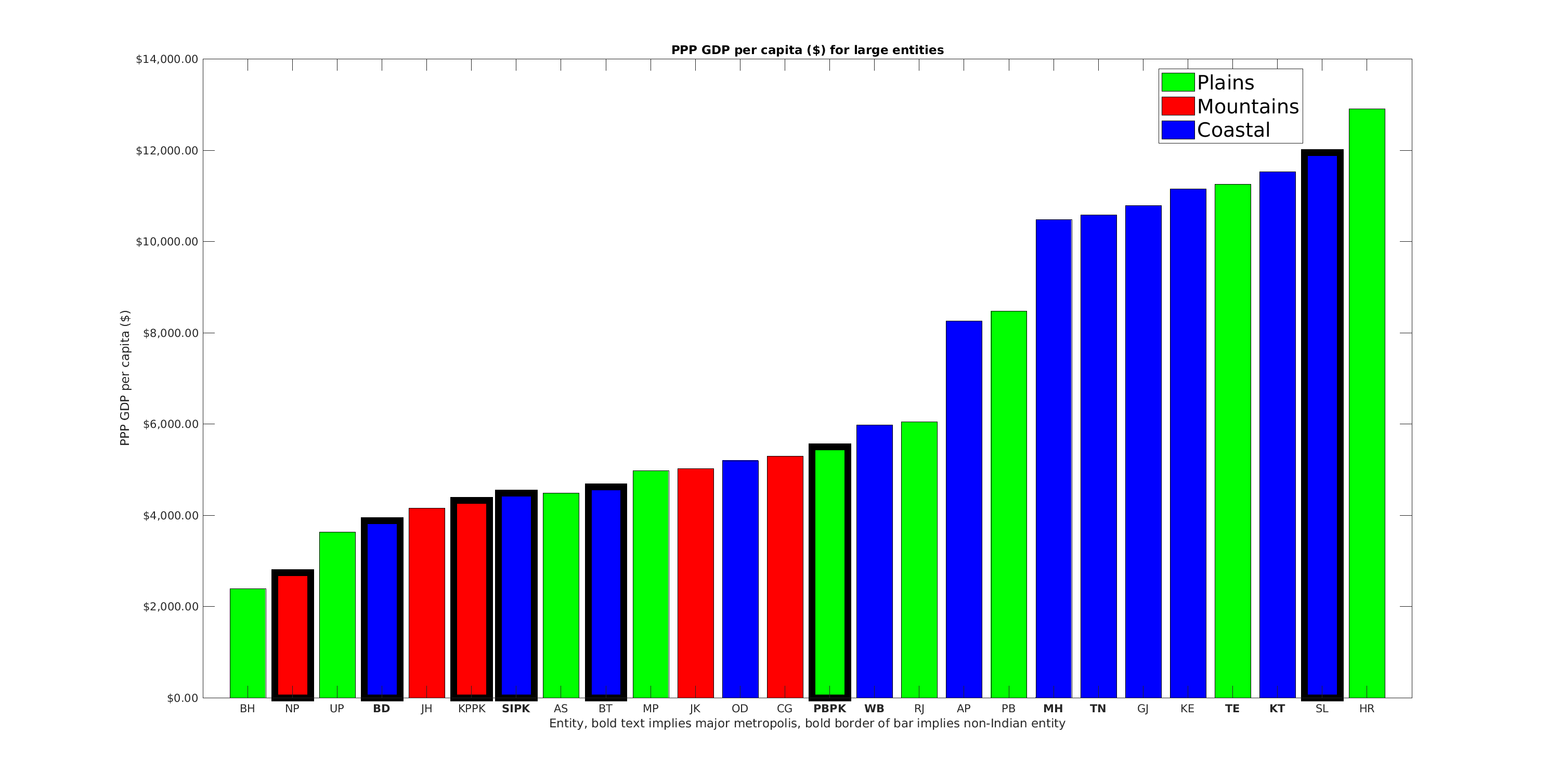

Seen in the two figures below are GDP per capita ($ PPP) figures for smaller (< 20 million population) and larger (> 20 million population) regions. The entities include the nations of Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, states and union territories of India, and provinces of Pakistan. Some notes about the two figures:

- Green bars denote plains regions, red mountain regions and blue coastal regions.

- Bold x-axis labels indicate entities with major metro areas.

- Bold borders around bars indicate non-Indian entities.

There are roughly five bands of wealth we can identify:

- Rich smaller entities of India: Goa, Delhi, Sikkim and Chandigarh. These have GDPs of around $20-25000.

- Richer large entities consisting of Indian states and Sri Lanka. GDPs are around $10-12000, and these are predominantly coastal regions.

- Succesful agrarian states of India (Punjab and Andhra), mountainous states of India (HP, UT, MZ), Pakistan’s capital Islamabad, and country of Bhutan. GDPs between $8-10000.

- Interior Indian states and Odisha, along with all Pakistani provinces. This is the South Asian mean performance of around 4-6000$.

- Poor regions: Indian states of UP, Bihar, countries of Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan’s remote area of FATA and India’s remote state of Manipur.

Clearly being on the coast and having a major city help in a major way. In this context, there are three regions which are major disappointments, India’s West Bengal, Bangladesh and Pakistan’s Sindh. All three are on the coast, have major metropolitan areas and even have rich agricultural lands. But their economic performance is significantly below potential.

On the other hand, the economic star of the subcontinent is the Indian state of Haryana. It defies every convention, its not on the coast, lacks a huge metro region and lacks abundant rainfall. But it excels in every aspect of economic activity, its agricultural productivity is second only to Indian Punjab, its industries are varied and well developed and its service sector is a leader in India along with Karnataka. Gurugram hosts genuinely innovative startups, home to at least 7 of India’s 30 unicorns.

An interesting comparison is that between the state of Punjab and the Pakistani province of the same name. Indian Punjab is richer despite lacking a metro area. But there is a convergence in certain aspects. These are rich agricultural areas, with strong remittance networks but they both might lack industrial entrepreneurs.

Bihar, Nepal and Eastern UP together continue to be home to the largest concentration of poor people on planet Earth. This is an isolated region, with no major cities, neglected by every Indian political entity for many centuries now. The Modi government’s national waterway one has already connected the region upto Varanasi to the ocean, upstream will be a technological challenge. Nepal, can look to Indian states like Uttarakand and Himachal for an effective growth strategy.

Although geography and history play a major role, the example of Haryana shows that those factors can be overcome. Market access, aggregation effects and the presence of mercantile communities are the key variables that determine economic performance.

“On the other hand, the economic star of the subcontinent is the Indian state of Haryana. It defies every convention, its not on the coast, lacks a huge metro region and lacks abundant rainfall.”

Very interesting post. But just wanted to comment on the above. Haryana’s metro is Delhi. Gurugram is a suburb / satellite of Delhi. I think that needs to be factored in somehow.

Also, how did you go about defining major metro? What thresholds? Which metros are incldued?

Thanks!

Hoju, Haryana has definitely been helped by the concentration of higher education institutions in Delhi. But the state itself has developed impressive educational institutions in recent years, including India’s largest cancer institute, an IIM at Rohtak, and a bunch of high profile private universities.

Regarding metros, my main threshold was the activity level at the airport. The threshold was a little bit different for India (10 million) vs other countries (5 million), since India tends to have a lot of domestic traffic.

Metros are:

India: Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai

Bangladesh: Dhaka

Pakistan: Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad.

I would not call Islamabad a metro, its glorified Chandigarh

I’ve had this exact thought before. Islamabad’s best comparable in India is Chandigarh. Both are planned cities.

Both look like great cities although a bit dead and lacking in character.

Comparing Chandigarh and Islamabad is attractive, but they differ in many important ways.

Islamabad is the national capital of Pakistan, so has a direct line of tax revenue. Chandigarh is a state capital, so its tax revenue stream is far more limited.

Its airport had 5 million passengers last year, compared to Chandigarh’s 2 million. Islamabad’s population seems to be more internationally connected, especially to UAE. There were 4 direct flights to Dubai from Islamabad compared to 1 from Chandigarh.

Agree with Hoju.

I think the most important factors for India to focus on over the long run are:

—physical health outcomes (not health care services)

—mental health outcomes

—intelligence outcomes

—what Glenn Loury calls “relations before transactions” or what is called “culture” for large groups of people

—academic excellence (not degrees, credentials . . . years of schooling . . . only outputs)

Of course India should in the short run focus on deregulation, simplification of regulation, simplifying the tax code, globalization, and mass physical infrastructure projects. But these only allow India to maximize outputs holding inputs constant. The above 5 increase inputs.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Vikram, please write additional posts. Are you willing to join Brown Pundits Brown Caste interviews?

Hi AnAn, I do write here from time to time. Regarding the brown cast, I am professionally an applied mathematician, so this is coming from an interested and (hopefully) informed layman, not an expert.

On Haryana i would just say that apart from the service sector, which is a byproduct of being Delhi’s neighbor, all its other strengths are sort of shared with its neighboring states, especially Punjab. So not as outlier as its made out to be.

Agriculture productivity, sports excellence, per capita GDP, HDI etc are very similar to Punjab. The only thing which it has , which Punjab doesn’t, is the service sector. The same can be said about Noida as well. I mean its nobody presumption that Nodia’s growth as a super city is due to some far sighted industrial policy of UP, right?

Gurgaon seems to be the central hub for business process outsourcing in north India given its proximity to New Delhi.

K P Singh who had a big role in developing it from a village to the success story it is now reckons it has fallen pretty short of what it could have been due to lack of political leadership.

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.livemint.com/companies/news/dlf-s-k-p-singh-retires-wishes-he-turned-gurgaon-into-the-city-he-dreamed-of/amp-11591282377174.html

Haha, DLF brings so many memories back. I was actually hired by DLF as a fresh undergraduate in India. Made all plans to live my life in India, as my then partner was based in Gurgaon as well. Life seemed pretty sorted out.

And then 2008 recession happened. DLF was hit pretty bad, and rescinded the offer, which crashed my dream. Got drunk and cursed America a lot. But everything happens for a reason,and decade later , lo and behold, i am in America 😛

One of India’s failures in the last few decades has been the inability to develop new cities.

Existing metros have been choking due to that.

Saurav, the growth of Haryana reflects a genuine structural change in the economy, with workers moving from low productivity sectors to higher productivity ones.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3566810

Ruchir Sharma has a good perspective on the lack of Indian growth which is due to

1) widespread anti-business and pro-welfare attitudes

2) heavy state ownership and involvement in multiple sectors particularly banking

3) disinterest in promoting semi-skilled manufacturing as a means to drive mass job growth. Elite interest is focused on highly capital and knowledge intensive sectors like IT and pharma.

4) labour laws discouraging scaling up by large employers.

5) poor infrastructure.

https://m.economictimes.com/markets/stocks/news/why-india-cant-be-the-next-china-and-shouldnt-try/articleshow/69089643.cms

Ali, Pratap Bhanu Mehta is perhaps India’s finest public intellectual, and he recently summarized research into India’s labour laws,

“It is a myth that India’s labour laws increased Indian labour’s bargaining power. As brilliant papers by Aditya Bhattacharjea of Delhi School of Economics showed, Indian labour’s wages stagnated, since the 1980s there was a massive decrease in strikes and lockouts, factories with hundred or more workers experienced more variability in employment than smaller firms. So the idea that Indian labour’s bargaining power was an obstacle to India’s industrialisation is errant nonsense.”

Therefore, I am an unconvinced by these labor law type lamentations. I have read the Industrial Disputes Act, my family members have factories in India, from personal experience it isnt the problem these non-scholars make it out to be.

Also, how would you then explain the success of coastal states and Haryana ?

Vikram….your post is silent on the contribution of politics and culture. It is the primary mediation mechanism for a sustained prosperity curve. The Meiji Restoration in Japan in the 19th century is a much studied phenomenon by many scholars – politics, historical and economics – and all of them site the primary impulse for the restoration in a socio-political movement.

For India, the regions (Eastern UP, Bihar, Nepal) that you cite as having no metros, lack of access has seen the biggest political consolidation in the last 5-7 years. All the three regions are seeing a tremendous infra push (DFC, grid upgradation and agri-reforms) by the Modi Govt. Magadh is coming and it will convulse Asia.

“Magadh is coming and it will convulse Asia.”

I wish I was that bullish on the region but I’m afraid it’s another false dawn.

Can’t sustain growth without human capital and with limited state capacity.

I’d be happy if it could just reach average India levels.

Prats, the most important things are networks and the presence of an entrepreneurial elite. It is a strong economy that builds state capacity rather than the other way around.

Ugra, before Japan had the Meiji restoration, it had the Rengaku.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rangaku

Incipient curiosity about Western knowledge in Japan seems to have roots in the interest of the Japanese elite in Dutch medical expertise.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caspar_Schamberger

This combined with the fact that the Japanese elite, like the American remained non-colonized, and sought wealth via entrepreneurship rather than administrative positions in an empire played a major role in the divergence of the Indian and Japanese/American economies.

Wouldn’t exclusion from most of the high positions in empire tend to push Indian elites towards business and entrepreneurship? The population share of people employed by the Raj was small anyway.

That the Indian elite didn’t bother to become entrepreneurs could be that there were few profitable opportunities and therefore they focused on obtaining cozy government jobs.

In addition, there are studies showing that Japanese labour productivity grew much faster than Indian in 1900s cotton textile mills despite both using the same technology. Inefficient labour rather than inefficient entrepreneurs was the major source of divergence. A Japanese firm even attempted to run a mill in Bombay but couldn’t reach Japanese productivity levels.

Around half of Indian billionaires are Gujarati, an ethnic group that makes up 4% of India’s population. There is definitely a sociological and historical angle to who chose entrepreneurship in India, aside from any market conditions.

Think of the sheer number of cantonment towns in the Gangetic plains versus Gujarat. The entry into these cantonments as workers (and later as residents) meant an entry into the modern world for the local elite, which would compensate for the exclusion from the highest levels. It is a bit like H1B Indians from today who choose relatively low level positions at companies in America, even though they could have had businesses to run in India.

India’s literacy rate was around 12% in 1947, Japan’s was 40% when the Tokugawa shogunate collapsed (1868). The Tokugawa shogunate made major investments in literacy which probably led to the higher productivity levels you are mentioning.

I agree that certain groups took the entrepreneurial lead, the Parsi dominated Mumbai is a major example of that. Even in Calcutta most factory workers were not Bengali and management was British or Marwari.

I would not say that literacy was important at the time for most industrial jobs, much of which consisted of manual and repetitive labour. Burma had high literacy and schooling rates for the time period yet most factory work there was done by Indians. How much do most people remember and use from school aside from reading and writing?

My understanding is that factory productivity is determined mostly by productivity and skill of its management, and mid to high range technical workforce like electricians, welders, machine operators and planners.

The bottom level assemblers indeed have repetitive work and are not the main value adders.

I think it is this abundance of factory level technicians that India would have lacked due to its low literacy. I think this is an area which China maintains an edge over India right now.

As a resident of Haryana I think I should point out that a substantial part of the growth in Haryana is due to the environs of Delhi. The whole belt from Sonepat to Palwal is tied to the growth of Delhi. This includes the two obvious suburbs of Faridabad and Gurgaon but also the entire belt along the Western Expressway that bypasses Delhi.

Haryana is not an isolated case, Himachal Pradesh is doing equally well, and before the Khalistanis shot Punjab in both feet, driving out entrepreneurs and industrialists, it was on the top of the list for most development statistics, as India Today magazine showed for many years. Uttaranchal will do well and so will UP if they break it up into manageable sized entities.

This is addressed in some of the comments above. Haryana’s growth is not just about Delhi, also Gurgaon has the headquarters of many companies, doesnt make sense to call it a suburb.

Regarding size, the data doesnt indicate that size has a big effect on prosperity.