The shadow of peasant past: Seven generations of inequality persistence in Northern Sweden:

We use administrative data linked to parish records from NorthernSweden to study multigenerational inequality in education, occupations, and wealth from historical to contemporary times. Our data cover seven generations and allows us to follow ancestors of individuals living in Sweden around the new millennium back more than 200 years, covering the mid-18thcentury to the 21st century. In our sample of around 75,000 traceable descendants, we analyze (a) up to 5thcousin correlations and (b) dynastic correlations over seven generations based on aggregations of ancestors’ social class/status. With both approaches, we find that past generations structure life chances many generations later, even though mobility is very high. The persistence we find using cousin and dynastic correlations is much higher compared to a simple Markov model limited to sequential parent-child transfers, but we also find that direct ancestor associations are very small. This suggests that there is a weak but constant kinship influence that attenuates slowly over generation.

These results align with Gregory Clark’s work in The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility. Last summer Clark told me that he is done with a draft of a new book that confirms and extends the data and argument from The Son Also Rises: though generational mobility is high in the short term, there is a long term persistence of social and economic status across lineages.

These results align with Gregory Clark’s work in The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility. Last summer Clark told me that he is done with a draft of a new book that confirms and extends the data and argument from The Son Also Rises: though generational mobility is high in the short term, there is a long term persistence of social and economic status across lineages.

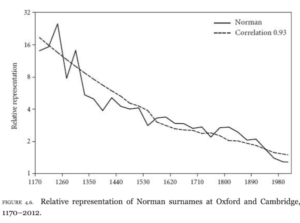

To me, the most striking element of Clark’s data is the persistence of Normans in the British elite. Though 0.30% of the British population at most, they were 16% of the student body at Oxbridge in the 12th-century. The proportion of Norman surnames at Oxbridge did not converge to the population proportion until the late 20th-century! This means it took nearly 1,000 years for Normans to regress (they are still over-represented in the British officer corps).

This tells us that social mobility over the generations is a thing. But, it also tells us that social mobility converges very slowly. This is intuitively surprising because single generation-to-generation changes in status are so extreme that one would predict the converge would happen much faster. Often one sees generation-to-generation correlations of income on the order of 0.50. But Clark’s data suggests that the systematic biases across many generations of status are such that the correlation would be closer to 0.90 to explain these results without an underlying phenomenon.

This tells us that social mobility over the generations is a thing. But, it also tells us that social mobility converges very slowly. This is intuitively surprising because single generation-to-generation changes in status are so extreme that one would predict the converge would happen much faster. Often one sees generation-to-generation correlations of income on the order of 0.50. But Clark’s data suggests that the systematic biases across many generations of status are such that the correlation would be closer to 0.90 to explain these results without an underlying phenomenon.

Why is this relevant? Clark had more access to surname information from Europe. But his data now extends internationally, and Clark claimed that this pattern is a cross-societal, and, the “intergenerational correlation” is very high. This includes India (in fact, some of the material in The Son Also Rises indicates that the correlation is higher in India than elsewhere).

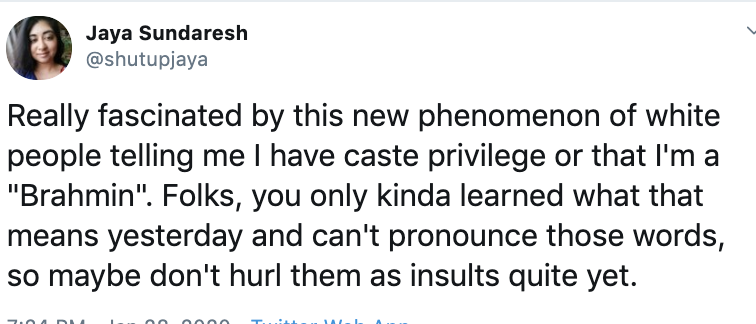

This is the context where we have to understand comments like this:

There are two major dimensions to understand this.

When people are beating you down for being a “terrorist” it doesn’t matter if you are a Brahmin or Dalit, a Hindu, Muslim or Sikh. North Indian or South Indian. Light-skinned or dark-skinned. All that matters is that you are brown. There are some people who are white-passing or black-passing among subcontinental origin individuals, but these are the small minority.

Insofar as “white supremacy” is what you think determines the lot of non-white peoples in the United States, talk of caste privilege seems quite silly. It is correct that Indian Americans tend to come from “upper castes” and the socio-economic elite. But what if you think that the only thing relevant about an Indian American with a Ph.D. is that they are a “person of color” (or as they say now a “black and brown body”)? Then that caste/class privilege really doesn’t matter in this country. All that matters is what white people think about you.

But I think this view is wrong. No one in the United States cares you are an Iyer. But what Greg Clark’s data suggest is that it’s not just your name, it’s not just what other people think of you Your inherited “capital” matters. A very dark-skinned Nasrani from a line of doctors may not be comparable to the descendants of slaves and farm laborers. It’s not because they’re Nasrani. It’s because they’re the descendants of doctors.

I don’t personally know Ammar Rashid, but I know many people like him and many people who either went to school with him or moved in the same circles. Unlike many (most?) Pakistani students who study abroad and develop a deep understanding of the mess that is Pakistan, Ammar Rashid chose to return to his country. He lives his life according to what he believes in (no matter how unpopular those beliefs and ideas may be), and not a lot of people in Pakistan can say that. I heard

I don’t personally know Ammar Rashid, but I know many people like him and many people who either went to school with him or moved in the same circles. Unlike many (most?) Pakistani students who study abroad and develop a deep understanding of the mess that is Pakistan, Ammar Rashid chose to return to his country. He lives his life according to what he believes in (no matter how unpopular those beliefs and ideas may be), and not a lot of people in Pakistan can say that. I heard