In the post 9/11 years, a multitude of “Pakistan experts” emerged and the bookshelves were flooded with books containing the words ‘Pakistan’, ‘crisis’, ‘storm’ or ‘battle’. In my opinion, very few writers from outside Pakistan (and even inside) have explored the country, its politics and its regional dynamics pre- and post-9/11. I consider Shuja Nawaz as one of the authors who, both as an insider and an outsider, written about Pakistan’s civil-military imbalance and foreign policy while maintaining balance and equanimity. I would like to disclose here that I have benefitted personally from Shuja Nawaz’s actions in the past. I was selected as one of the fifteen ‘Emerging Leaders of Pakistan’ (ELP) selected by Atlantic Council’s South Asia center (headed by Shuja) in 2012.

A little backstory: I was in a strange place in my life at the time. I had just finished medical school and had started my internship in internal medicine. My life was in flux. In the last year of medical school, I had drifted away from medicine and towards political science and history. Following Salmaan Taseer’s assassination in 2011, I had taken night classes at a makeshift school on political economy and history (more on ST’s assassination and my transformation here ). I had also started writing for my own blog and later for express tribune’s (ET) blogs and for Viewpointonline, a fledgling left-wing weekly. By the time I started my internship in May 2012, I had been published in ET, Pakistan Today and Dawn Blogs. During medical school, I had taken part in student politics and was aware of the brewing ‘Doctors Movement’ which was headquartered in the same dorms where I lived. In June-July 2012, there was a massive strike across Punjab and many of my classmates who were interns got arrested and were placed alongside death row inmates in Lahore. I wrote about this for ET and Dawn and engaged in twitter and Facebook wars with people who saw no benefit in our strike. A week after the strike was over, I received an email from Shuja that I had been selected for ELP and would be visiting the US in October-November 2012. I had earlier done an online interview and an in-person interview (after a typical 40-hour shift at the hospital) during the selection process. The other 14 people came from different backgrounds (Activists, NGO people, media people) and I was selected as a writer. We met General Mattis at Shuja’s house in Virginia, Lt Gen Douglas Lute (Obama’s special rep for Af-Pak) in the West Wing of White House and Chuck Hagel at the Atlantic Council. We also visited the Pentagon and Hoover Institute in San Francisco where we met George Shultz. Most of these meetings came about due to personal connections and efforts by Shuja and his staff. One of the dominant themes of our conversations was the status of Pakistan post-2014 ‘withdrawal’ of the US from Afghanistan. We also got a two-hour masterclass in US-Pakistan history from Shuja while we were stranded at our hotel in NYC due to Hurricane Sandy (and had to cancel our meeting with then-Mayor of Newark, Cory Booker). I wrote a few blogs for the now-defunct website for the fellowship that can be accessed here, courtesy of way back machine.

Personally, that first visit to the US in 2012 changed a lot of things for me in the short and long run. The fact that I’m writing this while sitting in the United States with a pretty stable life owes a lot to that selection. I have met Shuja over the years both in the States and in Pakistan and have learned a lot from him. I rate his earlier book ‘Crossed Swords’ (which I have a signed and amended-by-the-author copy of) as one of the best books on Pakistan’s military-industrial complex and its impact on Pakistan’s history.

Moving on to the next book. Shuja has been close to many of the protagonists in the book on both the US and Pakistani side. He grew up in a military family and his brother Asif was Chief of Army Staff in the early 90s, before his sudden death. He has been called the ‘Pakistan army’s man in DC’ by some people in Pakistan over the years. Having read books on Pakistan-US relations in the last decade (including but not limited to: Directorate S, The Dispensable Nation, War on Peace, India vs Pakistan, Sleepwalking to Surrender, The Wrong Enemy, The Way of the Knife), one gets a general outline of the ebb and flow of the relationship between the two countries. What Shuja’s book does is to add an insider’s narrative on the events and puts things in perspective. It starts off on the Pakistan side with the political reshuffling underway in 2006 when Musharraf wanted to sign an NRO with Benazir Bhutto (BB) and a few months before that Nawaz Sharif and BB had signed the Charter of Democracy. Musharraf wanted to share power with BB but on his own terms, as a dominant partner. BB was not interested in such a lopsided setup and was gathering allies in the US before her trip to Pakistan. Musharraf was fighting many fires in 2007, the chief one among them was ‘Lawyers Movement’, allegedly an internecine conflict involving different intelligence agencies. BB landed in Pakistan in October and faced a bomb blast in which she survived but more than 100 of her dedicated party workers perished. In December, BB was not so lucky and became the target of another assassination attempt. Musharraf had lost the plot. Fresh Elections were held and BB’s party took control of the Federal government. Musharraf tried to maneuver a role for himself in the democratic setup but had to resign in August 2008. It was a new era for Pakistan and the political class was in charge after 9 years of complete military rule. Shuja was a first-hand witness to BB’s deliberations in the US and provides an insight into her mindset and that of Zardari at the time.

There was a change of guard in the US as well. Obama was elected President on the promise of quitting the useless, forever wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In the first Obama term, there was the morass known as ‘Af-Pak’ policy review with State Dept, CIA, Military on one side and Richard Holbrooke on the other. In the end, with all possible information, Obama chose to announce an exit timetable from Afghanistan alongside a surge of troops. That was a blunder, as has been acknowledged by people in the Obama Foreign Policy team. The details of this process have been documented by Steve Coll and Vali Nasr in their respective books but Shuja provides further insight gained from candid interviews with key stakeholders and policymakers including Bruce Reidel. One particular thing that caught my eye was the discussion on Haqqani Network. I have always wondered why Pakistan protected them with such rigor and passion. A ‘senior Pakistani army officer’ told Seymour Hirsch that Haqqanis had “facilitated the evacuation of ISI personnel and their friends from Kunduz” and that was why they were regarded highly. Shuja thinks its not the right answer and I tend to agree with that. I wrote about the infamous Kunduz airlift here (link) and wish more Pakistanis would know about that incident.

With the arrival of Obama, the Musharraf-Bush ‘bromance’ post-9/11 was also over. Pakistan had received generous US aid and support (Non-NATO ally status and more) as a result of that relationship. The year 2008 changed that. Things went from bad to worse in 2011 though. Shuja has reserved a major chunk of his book on what happened in that fateful year. It was the year of Raymond Davis, of the OBL operation (my first ever blog for Dawn was on the OBL raid and I remember writing about the incident in Urdu while sitting in a General surgery lecture during May 2011), Memogate and Salala. I remember being quite up to date with the news at the time but Shuja’s narrative on all of these events, particularly the Memogate and Salala has added to my understanding of how the events unfolded and divergent viewpoints of protagonists.

He devotes a chapter to the issue of Financial Aid from the United States to Pakistan. It is a complex topic that involved failures on both sides. I have talked to many friends in Pakistan about this who work in development/human rights organizations and they told me stories of how cumbersome the process of getting funds from USAID is and the need for publicity often has to be weighed against the image that the US has in Pakistan (which is overwhelmingly negative). That is the reason why some of the leading human rights organizations (e.g HRCP, Shirkat Gah) in Pakistan don’t even apply for grants and funds from US sources. There was (still probably is) a whole industry of ‘grifters’ who arose from the post 9/11 largesse by the United States. In the mid-2000s till recently, using the words ‘combating religious extremism’ was a very good way to get international aid in Pakistan, a fact that has been criticized by actual human rights activists. Many religious figures also used this opportunity to get US visas and money in the guise of fighting religious fundamentalism. Shuja writes about the much-maligned Kerry-Luger bill (in 2009) that was supposed to prioritize civilian aid to Pakistan and was disparaged from early on by the military. In the Tierney Repot in 2008, prepared by the US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform, it was admitted that “US brand in Pakistan had become ‘toxic’ over time”.

The New York Times wrote an editorial in 2015 titled ‘Is Pakistan worth America’s Investment?’ which Shuja quotes (and I find very true):

“Since 9/11, the United States has provided Pakistan with billions of dollars, mostly in military aid, to help fight extremists. There are many reasons to have doubts about the investment. Still, it is in America’s interest to maintain assistance—at a declining level—at least for the time being. But much depends on what the money will be used for. One condition for new aid should be that Pakistan do more for itself—by cutting back on spending for nuclear weapons and requiring its elites to pay taxes.

Military Aid and what Pakistan did with that is no different. The details about how the Navy claimed $445 per sailor from Coalition Support Funds (CSF) in June 2005 but $800 per sailor in December 2005 would be comical if not tragic. In contrast, Air Force charged $800 per person in 2004 and $400 in later years. The Army charged steadily at $200. Similarly, Navy charged $5700 per vehicle per month as opposed to Army’s less than $100 per vehicle per month.

For Pakistan-watchers and students of civ-mil imbalance in Pakistan, there are frequent nuggets of interesting information. For example, about the 2014 PTI Dharna, US Ambassador Olson told Shuja that “We received information that Zahir-ul-Islam [DG-ISI] was mobilizing for a coup in September of 2014. General Raheel Sharif blocked it by, in effect, removing Zaheer, by announcing his successor. Zahir was talking to the corps commanders and was talking to life-minded army officers. He was prepared to do it and had the chief been willing, even tacitly, it would have happened”. We also learn about the inroads made into military by Tablighi Jamaat (TJ) and the ‘Pir-Bhai’ system which distorts the discipline of army.

In my opinion, the book is recommended reading for people interested in Pakistan, its civil-military relations and how the US treats its relation with Pakistan.

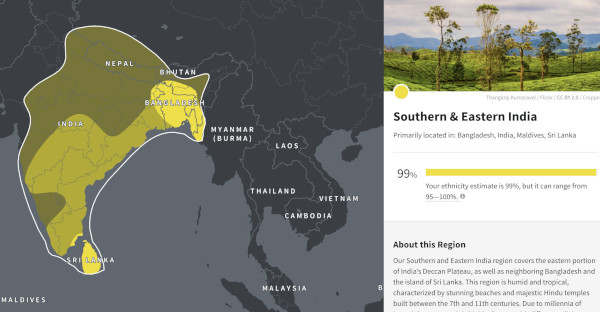

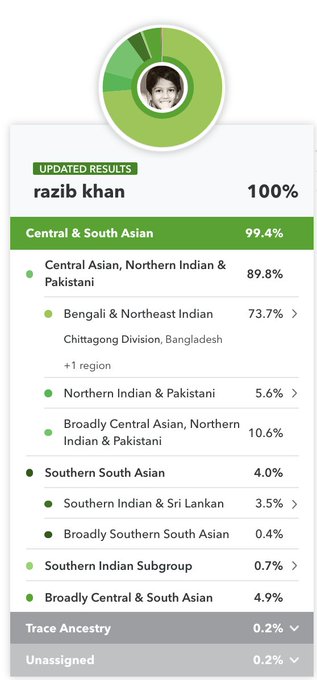

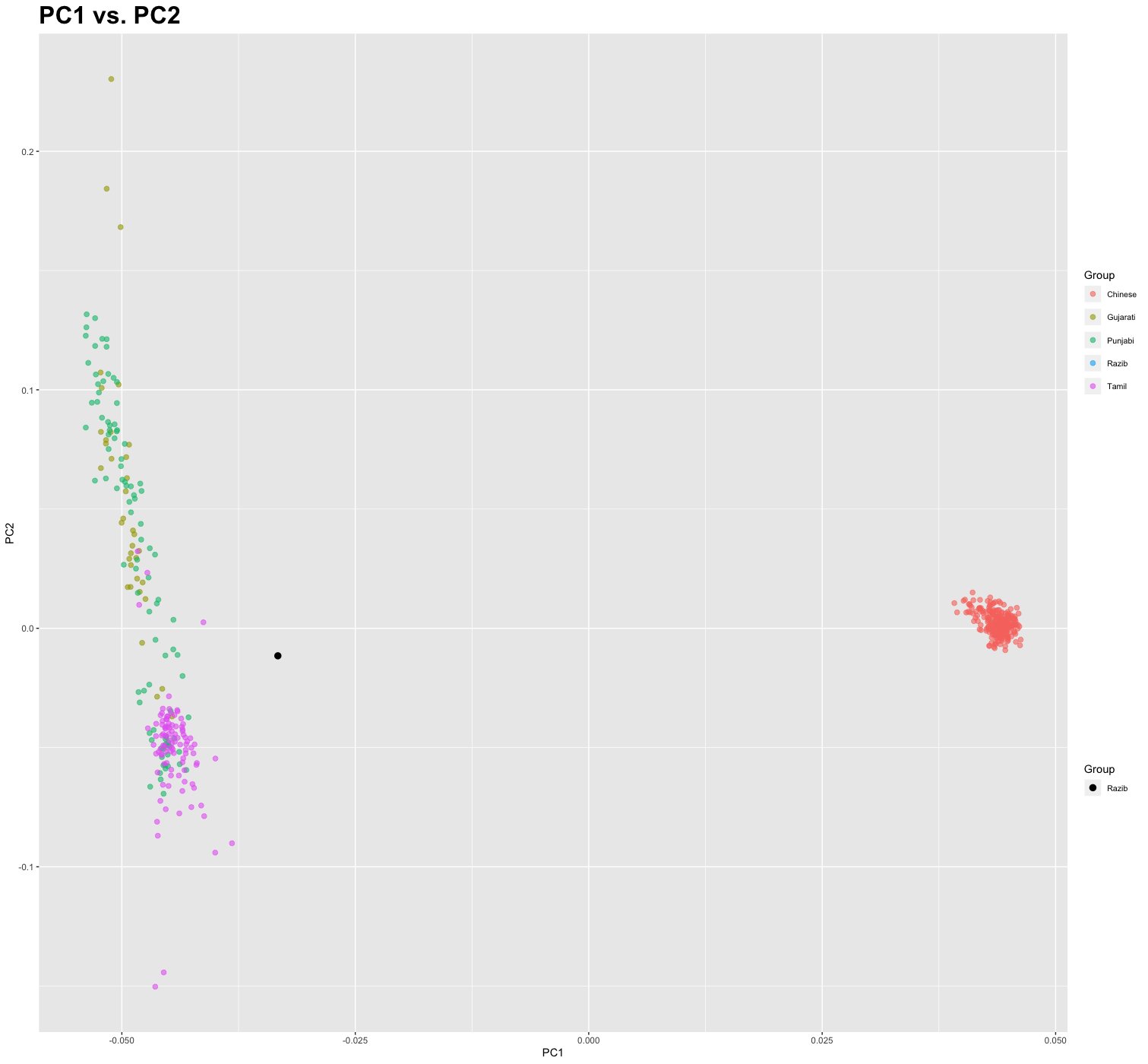

Recently I made a comment that I appreciate what 23andMe and Ancestry have done with their South Asian ancestry updates. My own results came into sharper focus. The algorithms did what they were supposed to do.

Recently I made a comment that I appreciate what 23andMe and Ancestry have done with their South Asian ancestry updates. My own results came into sharper focus. The algorithms did what they were supposed to do.

We chat with American Enterprise Institute’s

We chat with American Enterprise Institute’s