In the last podcast I was struggling with pronouncing the name, Jahanara.

The first is a Pakistani friend:

Audio Player

The second is an Iranian friend:

Audio Player

How Jahanara pronounces her name:

Audio Player

My pronunciation is in between the first two. There is some overlap between Persian and Pakistani (Indo-Persian) names of course. So I usually pronounce the name in the way I first heard it or heard it most.

Of course the “Hindi” pronunciation is different where the N in Jahanara is nasalised rather than pronounced.

The personal name “Jahan” seems to have retired from Persian and instead migrated to Hindustan. So I’m inclined to defer to the Urdu version of the name but nasaling the N is very unnatural to me as it reminds of the time at Urdu class. One of the students was counting the Urdu numbers with a Punjabi nasalisation and the teacher started chuckling.

I dropped the Urdu class after one semester even though I was making the fastest progress; Persian & Urdu are simmering languages for me, it’s easy to get to fluency but English almost always takes over.

As a final note; Urdu, by any other name would be just as sweet, but Persian is sweeter (I’ve mauled Iqbal & Shakespeare in a single sentence).

The irony is that Urdu was called Hindi since Urdu was initially used to refer the Persian of Shahjahanabad. Urdu is the regularisation of a Hindustani standard that came about through Amir Khusrao but was obviously was called Hindi as it was the local language.

As a final aside it is just astounding the extent to which India’s medieval history is in Persian. I *knew* that the official language was Persian but never understood what that meant entirely. The Indo-Muslim rulers were copious writers and along with their monuments left mountains of documents (Shah Alam’s unfinished Perso-Urdu verse ran to 600+ pages).

The reason Pakistanis and Urdu-speakers go on and on about Middle Eastern forebears is because their ancestors were certainly in that milieu for centuries. It’s a vestigial memory that has persisted.

Origin Myth of Urdu & Hindi by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

Of course one can never deny Pakistan’s aristocratic heritage when our dear Captain decides to wear a cheesy Shalwar Kameez in an audience with HM the Queen:

When meeting Royalty one should at least be aware of the sartorial graces. It looks like something he would wear to a shaadi in the Pind. Also Virat Kohli may be brash but his socks, shoes and pants do not go together at all!

If anything learn from the wonderful Noorie Abbas in how to dress:

ISI/RAW have trained this vixen well. Interestingly though the choice of a Sari was very unorthodox; Pakistan girls her age will never wear a Sari to a formal event. I know that the older generation in Pakistan wear it (one socialite NGO makes a point of wearing it everywhere) but it’s pretty much died down; I wouldn’t be surprised if Noorie has inadvertently kick started it.

Her pastel shawl and gray-blue top set off extremely well. It was an interesting thing in the Prof. Devji podcast that the main gripe Hindutva had against Muslims pre-1947 was their “aristocratic connotations”. After Independence when most of these people went across to Pakistan; the image of the Muslim changed to gangster and poor.

Pakistan’s structural inequality, which we explored in our educational podcasts, means that even though there is a very high National Asabiyah (in core Pakistan; East of the Indus); the Islamicate class structure is very much dominant.

So you have these extremes in Pakistan, which are not so apparent in other countries. Since Bangladesh shackled the yoke; it’s made tremendous strides since it seems so much more egalitarian (it may also be that Perso-Urdu culture is inherently hierarchical considering its origins despite a strong socialist tradition of Urdu Poetry).

The rest of the Pakistan nation is as lemmings off a cliff:

There was a comment below which I am now reflecting on…that this “This blog pertains to South Asians.” The comment was sincerely made, and I take no deep issue with it.

There was a comment below which I am now reflecting on…that this “This blog pertains to South Asians.” The comment was sincerely made, and I take no deep issue with it.

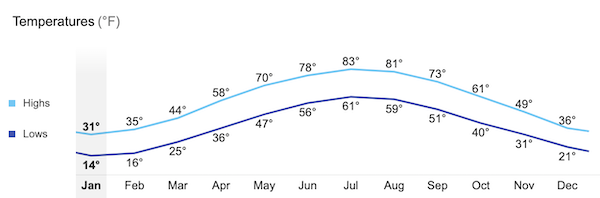

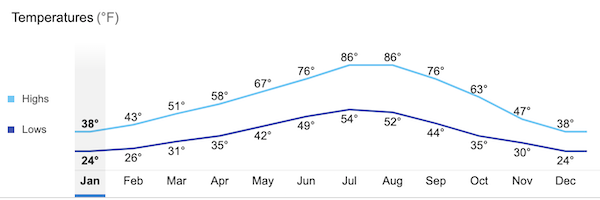

I wasn’t born in the cold and ice. But I was raised in it. I was moulded by it. I do not miss the seasons. I do not miss the ice. But the ice is part of who I am.

I wasn’t born in the cold and ice. But I was raised in it. I was moulded by it. I do not miss the seasons. I do not miss the ice. But the ice is part of who I am.