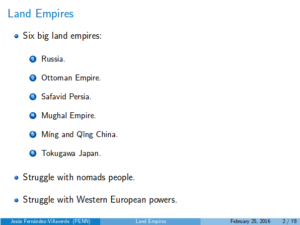

Excerpts from an an article

https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/sketches-from-the-south-the-rise-fall-of-amarapura/

The history of the Buddhist clergy, in this country, has largely been a history of schisms, splits, and amalgamations. Over the centuries, certain points have been inferred with respect to this process. First and foremost among them, that the breakdown of Buddhist monastic orders in response to growing caste militancy was only a partial, and not complete, consequence of the political games played by the British. Insignificant though this may be, it is nevertheless important in that certain writers paint a rosy picture of caste-ism while forgetting that the rifts between different castes were exacerbated once the British realised it could harness them to its advantage. Caste-ism was, in other words, waiting to be harnessed by external forces.

When the annexation of Kandy was complete, assurances were made by the Colonial Office that steps would be taken to preserve the privileges of the traditional elite, which obviously included the monastic orders (the Siyam Nikaya). Until then, the politics of the Kandyan Kingdom had followed a largely cyclical process, with shifting loyalties and shifts in the regime (particularly after the Nayakkars began their reign). But with the advent of the outsider, this was destined to be succeeded by a largely linear process, in which that outsider, the imperialist, managed to concentrate hitherto traditional privileges within his bureaucracy. The traditional elite, naturally anxious to preserve those privileges, sought to preserve them through their faith. It was in this context that the Siyam Nikaya was guaranteed the continuation of its practices, in part through the much vilified, controversial Kandyan Convention.

The two (Governor of Ceylon, Robert Brownrigg and John D’Oyly, Chief Translator and later Baronet of Kandy) promised to undertake three practices which had been the duty of the King: providing food to the temples from the Maha Gabadawa, holding the pageant of the Tooth Relic in Kandy, and maintaining the Dalada Maligawa.

Of the three, the first is the most interesting, since the adherence to and the abrogation of its practice is for me a good indicator of how the Colonial Office affirmed, and later derogated from, the practices of the traditional Kandyan elite. It took several decades for the British to abscond from taking part in the ceremonies of traditional society in India, and that was a consequence of the Mutiny, which took place in 1857. In other words, it took an entire Mutiny to turn the British away from Indian life and culture. In Sri Lanka, by contrast, only 17 years were needed for them to renege on their promises regarding that life and culture; by 1832, contrary to the provisions in the Convention, the Colonial Office had elected to do away with the provision of food to the monks, and instead replaced it with a scheme whereby an annual stipend of 310 pounds (or about 30,000 pounds, when adjusted for inflation) would be paid to the temples. This was an uneasy proposition from the start, and was doomed to stall.

those rebel sects were quickly coming up. Their emergence was conditioned by the regions they originated from. In the hill country, the dominant caste was Govigama; in the low country, the dominant castes were Salagama, Karawa, and Durawa. The Siyam Nikaya yielded to the pressures this soon necessitated, and years after its founding by Welivita Saranankara, it yielded to the dominant caste. Upasampada was restricted to this caste (which was not dominant in the low country, or along the coastal belt). This was true especially when considering how power was distributed in the bureaucracy, prior to the British annexation, between the different castes: while in Kandy the non-Govigama castes had their own headmen, the departments to which they were attached were overseen by Govigama chieftains.

In 1799, therefore, Ambagahapitiya Nanavimala, a Salagama monk who resided in Welitara (a Salagama stronghold), went to Burma with a contingent of five samaneras and three lay devotees. They stopped at Amarapura, where they were duly ordained in 1800, and from where they returned in 1803 to inaugurate the new sect at Balapitiya (another Salagama stronghold, in many ways more so than Welitara). This was the Amarapura Nikaya, and their trek to Burma was financed by a leading (Salagama) entrepreneur from the region, Dines de Zoysa Jayatilaka Sirivardana, most likely an ancestor of Cyril de Zoysa, who would lead the Buddhist revival in the 20th century.

It is a mistake to suggest that the British did away with feudal structures in the societies they colonised. Far from it. In societies advancing towards capitalism, as Marx correctly surmised, such archaic structures would give way to an industrial class, which is why and how the Tories yielded to the Whigs. Such a transformation did not come about in the colonies. The reason is obvious. The British did not want to be the catalyst for the sort of change that would empower a nationalist bourgeoisie in the countries they had conquered. The one link with the past that those countries had which would hold back such a transformation was those feudal structures. In India, Africa, and of course Sri Lanka, the conqueror resorted to them, and in resorting to them, he found the perfect way of keeping us locked in the past. Those who believe that feudalism is retrogressive would be surprised to learn that the British didn’t really combat it. Instead, they encouraged it. That was their game, after all. Divide and rule.

This is where we must credit the Amarapura Nikaya, because for the first time in the history of the Buddhist order, it brought forth (as Professor Malalgoda observes) “closer cooperation between the monks and their devotees.” This had less to do with an overt objective by those monks to erase caste distinctions than with the fact of their own meagre historical condition: given that it had no royal patronage, the Amarapura Nikaya was compelled to rely on the lay devotee. As an anthropologist once wrote, moreover, this had an impact on the way even the Govigamas saw it: “I know many villagers of the Govigama caste who prefer to give alms to monks of the Amarapura or Ramanya Nikaya rather than those of the Siyam Nikaya because they believe that the former are less worldly.” Here, then, was a Buddhism that promised people salvation in this present birth, as opposed to the more conservative Buddhism which gained prominence among urban followers in the latter part of the 19th century.

Bana shalawa or Prayer Hall of the main Temple of Amarapura Nikaya, at Balapitiya. Most likely a church originally. Quite a few Buddhist Temples down south that have Church buildings (eg. Dodanduwa/Kumarakanda Temple and Shailabimbaramaya Temple, Dodanduwa; note Unicorns)

http://trips.lakdasun.org/visit-ancient-temples-at-kataluwa-totagamuwa-and-balapitiya.htm

![[ God being taken for a ride: photograph via newjaffna.com ]](https://www.colombotelegraph.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/jvc_pull_ther.jpg)