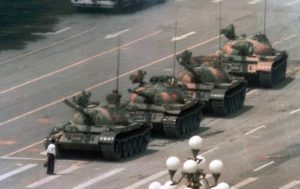

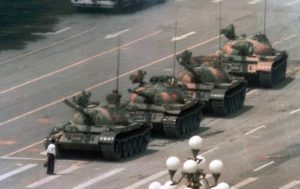

It has been 29 years since the Tiananmen Square incident, a students revolt that shocked the world, especially the photo of a young man standing in front of a tank.

I was working at a big cancer hospital last year and by complete accident, found a guy in the faculty who was at Tiananmen Square and escaped China in eary 1990s. I talked to him about it last year and an account of that was published in Daily Times. I changed some names and places due to privacy concerns.

Doctor Yang doesn’t look like a typical revolutionary. A diminutive, well-dressed man with an unassuming aura, he doesn’t fit the stereotype of an agitator. However, he has been a rebel at heart for a very long time. At the age of ten, he asked the local communist party leader why the fruits of liberalisation of economy seem to fall in the laps of party members only. Lucky for him, the communist leader was a friend of his father and he escaped any punishment for such ‘rebellious’ ideas. Growing up in the Chinese countryside during the 1980s, he was destined take over the farming job his father had performed before him. The family fortune had faced an about-turn after the ‘Revolution’ in 1949. His grandfather, a school teacher, was branded as ‘bourgeoisie’ and thus an enemy of the people. His father had to take refuge with his in-laws, in order to escape the wrath of the ‘Revolutionary’ government. Doctor Yang was lucky enough to get admission to a prestigious medical college in Beijing where he pursued his undergraduate studies. During the second year of his undergrad studies, an incident changed him forever. He was not a politically active student but he had decided to protest alongside his comrades during the months of May and June, 1989.

The winds of change were sweeping the world as the decades-long cold war between United States and Soviet Union was coming to an end. After the disastrous reign of Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev had steadied the ship but mass scale industrialisation and social engineering had led to a society on the brink of failure. In China, Chairman Mao had presided over one of the biggest man-made famines in the history of humankind, in addition to subjecting his citizens to the ‘Cultural Revolution’. The United States had witnessed its own sociocultural changes in the immediate post-World War Two era which unleashed the combined genie of consumerism and marketing. By the 1980s, the United States was progressing economically while the Soviet economy was stagnant and China, under Deng Xiaoping, had decided to liberalise the economy. The focal points of these reforms were Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, who furthered the agenda set by Deng Xiaoping. Mr. Xiaoping is credited as the architect of a new brand of thinking that combined socialist ideology with pragmatic market economy whose slogan was “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”. Deng opened China to foreign investment and the global market, policies that are credited with developing China into one of the fastest-growing economies in the world for several generations.

The liberalisation project in China faced numerous obstacles created by the ancien regime (including Li Peng, an adopted son of Zhou En Lai). Deng, instead of falling on the sword himself, credited Hu Yaobang for the changes. When widespread student protests occurred across China in 1987, Hu’s political opponents successfully blamed him for the disruptions, claiming that his “laxness” and “bourgeois liberalization” had either led to, or worsened, the protests. Hu was forced to resign as Party general secretary in 1987, but was allowed to retain a seat in the Politburo. Meanwhile, Hu’s standing among the youngsters had skyrocketed and they admired his fortitude and personality. Hu passed away on April 15th, 1989. A day after his death, a small-scale demonstration consisting of primarily college students, commemorated him and demanded that the government reassess his legacy.

Doctor Yang was among the students who thronged the streets of Beijing, protesting against the government. The protests starting in April, mushroomed into a daily occurrence until Primer Li Peng declared Martial Law in Beijing on 20th May. Around 250,000 soldiers were present in the capital following the order. Tens of thousands of demonstrators surrounded military vehicles, preventing them from either advancing or retreating. The troops were ordered to stand down after four days. The student leaders of the movement including Liu Xiaobo (who recently passed away while in custody of the Chinese government) wanted to turn the protests into a pro-democracy movement.

On June 1, Li Peng issued a report titled “On the True Nature of the Turmoil”, which was circulated to every member of the Politburo. The report indicated that students had no plan to leave the square and there was ‘Western’ backing for the movement. On the evening of June 3, army units descended upon the city and opened fire at the Wukesong intersection, about 10 Kilometres away from the Square. On 4th June, tanks rolled in Tiananmen Square, the epicenter of protests. The infamous ‘Tank Man’ picture from that day remains an iconic reminder of the incident. The official number of people killed due to that military action is a source of speculation since the Chinese government never released figures about that. Dr. Yang lost one of his friends that day and his roommate spent six months in jail after the event.

He channelled his rebellion from the corrupt communists to diseases affecting the human body, finished his medical studies and left the country at the earliest opportunity. He spends most of his time doing research in the United States. Sometimes, the best that a patriot can do for his country, is to leave it.

One of the more interesting and definite aspects of David Reich’s Who We Are and How We Got Here is on caste. In short, it looks like most Indian jatis have been genetically endogamous for ~2,000 years, and, varna groups exhibit some consistent genetic differences.

One of the more interesting and definite aspects of David Reich’s Who We Are and How We Got Here is on caste. In short, it looks like most Indian jatis have been genetically endogamous for ~2,000 years, and, varna groups exhibit some consistent genetic differences.

Yes, caste seems invisible in Pakistan’s bigger cities (Lahore and Karachi) and one can say that caste doesn’t play a role in daily life BUT it matters during elections, during matrimonial activities and during dealings with the state bureaucracy. If you ever go to a government office (Police, Judiciary, Income Tax), try looking at the leaderboard of that office’s previous incumbents there and notice how most people on that list have their caste listed after their name. Also, go to the district courts in Lahore or any city and see how many lawyers have mentioned their caste after their names.

Abdul Majeed

As an aside I was googling John O’Brien and came up with a few interesting snippets about the Pak Christian community:

c) Great honour is given to the Bible and compared with many older and more developed Churches in other countries, there is real familiarity with its text and message. There is a richness here which cannot be overlooked. In fact it cries out to be contextualised and deepened. The singing of the Psalms in Punjabi is a very distinctive and enriching feature of church life here. Yet this esteem for Sacred Scripture could be undermining of a real sense of Church inasmuch as it is conceived in rather Islamic terms: there is an unspoken assumption (a false one) that the Bible functions in Church life and theology as the Quran sherif does in Islam. This leads to and is further exacerbated by the prevalence of a literalist and fundamentalist reading and preaching of the text. As a result, all sorts of self-appointed preachers abound, each offering a more exotic explanation and application of the text. Rivalries increase and with them, factionalism. There seems little sustained effort to promote a communitarian reading of Scripture, contextualised on the one hand, by the living tradition of the People of God and on the other, by the concrete struggle for justice and dignity which is the daily bread of our people.

A) Strengths:

The Church which under God’s grace, has come into being here in Pakistan has many fine qualities and strengths:

i. It continues to exist and grow in a non-Christian and non-supportive environment:

ii. It is very much a Church of the poor, God’s chosen ones:

iii. It is engaged in an on-going and far-reaching practical ecumenism:

iv. It is a Church with a profound religious sensibility:

v. There is a growth in local vocations to ministry:

vi. At all levels it is socially involved; both “religiously” and “developmentally”:

vii. It has a highly developed organisational infrastructure:

viii. Among the People of God there is a tangible love for “The Word”:

xi. The Church membership has retained a strong cultural identity: the Church in Pakistan is very much a Pakistani Church.

x. The communities have a very strong identity as “Christians”

xi. Among Pakistani Christians there is a very solid sense of family and kinship.

xii. There is a strong devotional life with many indigenous resources; songs, pilgrimages, Marian meals etc.

This is the light; if there is light there is also shadow!

B) Shortcomings:

i. At nearly all levels, the Christian community can be easily divided by the factionalism (partibazi) which characterises social relations and by the consequences of other internalised oppression:

ii. It is a Church massively reliant on foreign money:

iii. It is constantly under threat externally and internally from fundamentalism and sectarianism:

iv. The Liturgy has been translated but not inculturated:

v. There is an impoverished Eucharistic sense:

vi. A dependency mentality is still very stong:

vii. Politically, psychologically and even physically it tends to be ghettoised:

viii. The culture is consolidated but seldom critiqued by ecclesial praxis and therefore not sufficiently enriched by faith:

ix. In general terms, the leadership remains authoritarian or patenalistic, reinforcing the dominant socio-political pattern rather than offering an evangelical alternative to it:

x. The dignity and role of women are scarcely recognised:

xi. There is little or no missionary outreach:

xii. It mirrors the society in that personal freedom and responsibility are not really valued above conformity.