“The Man on Mao’s Right” is the memoir of Ji Chaozhu, a Chinese diplomat who worked as an interpreter for several decades before being promoted to more substantive positions, ending his career as China’s ambassador to Great Britain and a stint as undersecretary general of the UN. His personal story in intertwined with many important events in modern Chinese history, from the Japanese invasion and a peripheral role in the communist’s rise to power (his older brother was a confidant of Zhu Enlai and more or less a Chinese communist agent in the United States), to the Korean war, the early decades of Chinese communism, the Great Leap Forward, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the fall of the Gang of Four and the rise of post-Maoist China under Deng Xiaoping.

Ji went to school in Manhattan and was a scholarship student at Harvard before most of the family moved back to China to help Chairman Mao build the new China. He is a Chinese patriot and a thoroughgoing Confucian Mandarin at heart, who managed to retain these ideals through decades of purges and ideological twists and turns in China, so he is not inclined to kick up controversy and cross the party’s red lines even in his old age. The memoir seems honest and frank enough when it comes to his personal life, but the politics and political commentary are filtered through a lifetime of extreme care and awareness of what words can mean and what limits are to be kept in mind. He may have exactly these beliefs and attitudes, or he may think these are the beliefs and attitudes he considers safe to share. Either way, opinions that the CCP now considers safe are freely shared, those that could upset the CCP apparently never entered Ji’s head. That’s just how it is in this book.

But that is not to say the book has no revelations. The everyday details ARE the revelation here. The bombed out moonscape of North Korea where the Chinese and North Koreans lived in tunnels as they battled the most powerful army on earth to a standstill (at tremendous cost); the truce village at Panmunjom and its peculiar diplomatic standoffs; the living conditions in the Chinese foreign ministry in the 1950s (his first “house” with his wife is a lean-to one room shelter with a tin roof and cardboard walls); the living conditions of the peasants he is sent to for “re-education” (they store urns of their urine, and have to keep them inside the room to prevent it being stolen by other farmers; it is valuable as fertilizer); the purges of the cultural revolution and the way people became “non-people” when they were out of favor (friends would not meet them, nobody would mention their name, as if they never existed); his struggles with Nancy Tang (the other famous interpreter of the day, who was closer to the gang of four, so she was able to push him around during the cultural revolution), how hungry Chinese diplomats were during the famine days of the Great Leap Forward and what it meant to eat good food abroad (they would save their meager travel allowance to buy dried milk for starving relatives back home), and so on and so forth. It is a fascinating life, and well worth reading about.

The section about the cultural revolution in particular is a must-read. Even though Ji is very intensely nationalistic and pro-CCP and is generally an extremely careful mandarin who has surely written this book with as much care about being on the right side of history as he was in his long service, he still paints a truly horrendous picture, one which is even more horrifying because of his calm detachment. He describes the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution as China’s “Lord of the Flies” moment, when the Red Guards were unleashed and society went mad. He estimates that in Beijing (in July and August 1966), about one person was beaten to death per block (in a city which has thousands of city blocks). How many countless thousands were beaten to death, blown up with dynamite, forced to eat shit or whatever other torture the young students could come up with, all across China, is incalculable. Children reported their parents, siblings stopped talking to suspect siblings. Sons and fathers disappeared and were not mentioned in case someone would slander you by association. People divorced their politically suspect wives, mothers hanged themselves as sons disappeared, and all this while the cadres being set upon were themselves (for the most part) fervent supporters of the CCP and the revolution.

It is noteworthy that Ji Chaozhu is much more shocked by the cultural revolution than he was by the Great Leap Forward. He himself estimates that some 30 million probably died in that (man-made) famine but he mentions it as a statistic, with no great feeling attached to it. The way he, his family and others of his background and class (educated mandarins) were treated in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution strikes him as a much worse crime than the way 30 million peasants were starved to death. This sort of makes sense, but is worth noting.

Ji (like many Chinese, even within the CCP) was supposedly a convinced communist, but the book makes almost no mention of any Marxist theory or analytical framework. Nor is there any explanation for why he, avowedly Marxist in 1950, saw nothing worth noting in China’s historic transition to capitalism. The impression he conveys is that while he diligently read the Marxist literature that was ubiquitous in his time, he was always far more “Chinese nationalist” than Communist. This may be his lifelong Mandarin caution speaking, or he may really be uninterested in Marxist economics or even in Marxism per se.

Anyway, a fascinating book. Well worth reading.

PS: A few years after the publication of his book, his wife told an interviewer: “Let’s just say we’re survivors..That’s what he’s trying to say.”

The Chinese edited Ji Chaozhu out of the official picture showing Zhu Enlai welcoming Nixon to China (possibly because the other interpreter, Nancy Tang, used her “pull”, or possibly just for aesthetic reasons)

Nancy Tang was semi-purged, but thanks to her younger age, has managed a comeback of sorts. Here she is in a recent interview:

Post postscript: I happened to read this account of Zhu’s famous remark while reading things around this book and just wanted to put it out there: The Financial Times this week reported that former foreign service officer Chas Freeman used a seminar honouring On China’s publication to reveal that Zhou’s famed remark about the impact of the French Revolution (“It’s too early to say”) was not translated properly.

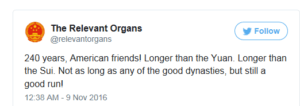

The comment is often mentioned in illustration of the long-term outlook of the Chinese leadership. But Freeman says it was all a misunderstanding. Zhou was talking about the 1968 student riots in Paris, not the events of 1789.

“I distinctly remember the exchange. There was a misunderstanding that was too delicious to invite correction,” says the retired US official.