This excellent article was written in 2002 by the redoubtable Dr Hamid Hussain. Still relevant.

Demons of December —

Road from East Pakistan to Bangladesh

Columnist Hamid Hussain makes an excellent analysis of events leading to 1971.

Introduction

Great blunders are often made, like large ropes, of a multitude of fibres.

Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable

December is the anniversary month of the independence of Bangladesh and break up of Pakistan. The memories of that critical period of the history of the two countries are very painful for everyone who was affected in one way or the other. There has been very little attempt to dispassionately and critically analyze various aspects of that period. Most of the writings have been limited to accusations and counter-accusations and mud slinging. In the absence of a serious government or academic inquiry, most of the facts have been clouded in only opinionated rhetoric. Some have picked up on one person and blamed him for the whole disaster. Others have tried to defend their favourite and passed the buck to someone else. Various individuals have played an important role during that critical time period and everybody had their share in the outcome. Most of the discussion has been limited to the last act of the play, which was played in 1971, ignoring the whole historical context. At the end stage of a crisis when the powerful currents of history are in full swing, as one commentator has correctly pointed that an individual cannot alter the movement of historical forces, which are far stronger than any individual actor.1

Several ethnic sub-groups in Pakistan, in addition to the clash on material issues have jealousies, deep-rooted prejudices and stereotypes about each other. In this environment of mistrust of each other and absence of conflict resolution models, open clash between various groups including use of violence becomes the general rule rather than exception. The ruling elite of Pakistan views the political consciousness of ethnic groups as subversive. They have tried to use ‘the twin instruments of Islam and the state to overcome this subversive force’.2 The state’s assertiveness to impose an artificial unity from above, where the ruling class is composed of a dominant ethnic group results in an expected response from other ethnic groups. They perceive it as imposition of the value system of the dominant ethnic group and loss of their own ethnic identity.3 This creates a vicious cycle, where every attempt to centralize control over periphery results is hardening of the attitude of the one’s at the receiving end. The threat to state’s territorial integrity ‘tends to arise out of local reaction to the centre’s heavy handed imposition of uniformity on diverse communities in the first instance, and the violent repression of subsequent local dissent’.4 This is the essential component of the whole affair. Bengalis had genuine grievances against the Western wing, but ‘their success came, when it did, not because their assumptions were more accurate than those permeating the Pakistani elite-culture but because their strategic alliance with Delhi and Moscow gave them an advantage Islamabad was unable to match’.5

Historical Background

‘You at least are not a Bengali’. Three different delegates from West Pakistan starting their conversation with Karl Von Vorys during All Pakistan Convention of Basic Democrats in 1962 6

The prejudice against Bengali Muslims has a long history and was quite prevalent long before Pakistan emerged as an independent state. Muslim intellectuals, elites and politicians, which belonged to northern India, had the picture of a Muslim as tall, handsome and martial in character. These characteristics were applicable only to Muslims of northern India. As Bengali Muslims didn’t fit into this prejudiced and racist picture, therefore they were ignored at best and when even allowed to come closer, were considered inferior. Bengalis were shunned despite their political advancement and strong resentment against oppression and tyranny. A large portion of Bengali Muslims was converts from Hindu low castes. The ‘noble borns’ of Bengal claimed foreign ancestry (Syed, Afghan, Mughal). The majority of Bengali Muslim population which had customs common with Hindu peasantry and had a proud sense of their language was not considered as ‘proper Muslims’ by some Bengali ‘nobles’ and almost all of West Pakistan. This perception later influenced the official decision to ‘Islamize’ and ‘purify’ East Bengali culture in Pakistan after 1947.7 The British theory of ‘Martial Races’ was generally well received by the natives in this background. The British classification considered Bengalis as part of ‘feminine races’. They were considered ‘feeble and spineless but clever’.8

In later part of nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century, several important Muslim leaders advocated division of India on the basis of separate Muslim identity. The prejudice against Bengali Muslims was so prevalent and widespread, that no body cared about them and did not consider them as part of Indian Muslim community. In fifty years, about 15 such schemes were proposed but not even a single one mentioned Bengal or Bengali Muslims.9 Sir Muhammad Iqbal who proposed the idea of Pakistan in his famous Allahabad address in 1930 did not include Bengali Muslims in his scheme. Chaudry Rehmat Ali who coined the word ‘Pakistan’ for his new country did not bother to fit the majority population of future Pakistan in his name. Generally speaking, Muslims of northern India considered themselves superior and more pure blood and despised Bengali Muslims, which they seem to equate more with Hindus rather than accepting them as brothers in faith. The Bengali leader, Fazlul Haq who presented the Pakistan Resolution in 1940 was forced to resign from Muslim League in September 1941. The Muslim League leadership never trusted Hussain Shaheed Suharwardy, who was the elected Chief Minister of Bengal. He was not given a seat at Working Committee of All India Muslim League. Upper class elite dominated Bengal Muslim League. It got political support from Khawaja Nazimuddin, financial support from Mirza Abul Hassan Ispahani and media support from Maulana Akram Khan.10

In 1947, when the new state of Pakistan emerged, there was a very unique and difficult dilemma facing the new nation. More than a 1000 miles of hostile territory of India separated the two wings. East Pakistan contained more than half of the population but only one-sixth of the land. In Eastern wing, population was more homogenous ethnically and linguistically while Western wing had five clearly diverse groups (Punjabis, Sindhis, Baluch, Pushtuns and newly immigrated Muslims from India called Muhajirs). In eastern wing, the non-Muslim population was 23% while in western wing only 3 %. Peasant proprietors dominated agriculture sector in Bengal compared to large feudal estates in West Pakistan.11 Bengalis were the most politically conscious group of Pakistan. In addition, there was a long tradition of strong leftist presence in Bengal. Literacy rate was 30% in East compared to 20% in West Pakistan.12 In 1950, East Bengal Provincial legislature passed a landmark bill called East Bengal State Land Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950. This law abolished the permanent settlement, which ended the Zamindari system that supported the landed elite. The land holding was limited to 100 Bighas (about 33 acres) which affected both Hindu and Muslim landlords.13 In my view this little known single piece of legislation was a crucial factor which would impact the future course of relationship between the two wings. This law rang the alarm bells in West Pakistani ruling elite, which was dominated by the landed aristocracy.

The demand for Pakistan had a ‘millennial appeal, which, for a while, covered up the deep divisions within the Muslim community’. After the emergence of Pakistan, there were demands for clarity as to what it stood for, and fissiparous tendencies began to set in.14 This is the historical context of the events up to independence in 1947, which is very important in understanding of the events, which plagued the country later.

Second Class Citizens of the New Nation

Your music is so sweet. I wish to God, you Bengalis were half as sweet yourself. Field Marshal Ayub Khan to his Bengali friend.

After independence, several factors contributed to the gradual widening of gulf between the two wings. The fundamental factor was the difficulty of West Pakistani elite to accept Bengalis as equal partners. The rapid alienation of Bengalis was partly due to the fact that Bengali elite’s access to power had traditionally been through political mobilization and not bureaucracy. In the absence of a democratic culture and stark absence of Bengalis from the two most important decision making bodies, civilian bureaucracy and military, made the Bengali apprehensions acute. The establishment of a highly centralized regime in 1958 and banning of political parties effectively cut them out of the national scene with no voice at national level.15

Poorly thought out decisions made by a small clique, which were either made in total ignorance of ground realities or with deep-seated prejudice against the Bengalis contributed to increasing Bengali alienation. In the absence of detailed thought out policies, which are discussed at various forums, resulted in total ignorance on part of the general population of West Pakistan what was being done to the Bengali majority in the name of national unity. The initial discontent was based on the language issue, when Pakistan government decided that there will be only one national language and that will be Urdu. Even Bengali Muslim League leaders (Tajuddin Ahmad and Abu Hashim) expressed their apprehensions about the neglect of Bengali and its consequences. In September 1947, government of Pakistan printed currency notes, issued coins, printed money orders and post cards in English and Urdu only. In 1947, the circular of Pakistan Public Service Commission had made provision of Urdu, English, Hindi, Sanskrit, Latin and other languages but made no provision of Bengali. In an attempt to ‘purify’ Bengali culture of Hindu influences, Pakistan government decided to change the script of Bengali. In total disregard of the local sentiments and even constitution itself, central government set up centres teaching Bengali in Arabic script.16 The Bengali protest started on this language issue. Pakistan government was forced to acknowledge Bengali as one of the state language in 1954 due to overwhelming Bengali demands but in the process, the gulf between two wings further widened.

Every genuine demand by Bengalis was denounced as a conspiracy to destroy Pakistan. The ruling elite dubbed the Bengali advocates of their rights as ‘anti-state’ and ‘anti-Islam’ and used epithets like ‘dogs let loose on the soil of Pakistan’. Suharwardy was threatened with the loss of his citizenship.17 The Punjabi Governor of East Pakistan, Firoz Khan Noon described the Bengali voice of dissent as a conspiracy of ‘clever politicians and disruptionists from within the Muslim community and caste Hindus and communists from Calcutta as well as from inside Pakistan’.18 These ill-thought policies of central government further hardened the Bengali attitude.

The debates about the future constitution of the country further revealed the different thought process prevalent among the representatives of the two wings. A very important fact, which has been overlooked, is the membership of first Constituent Assembly. It had 44 members from East Bengal, 22 from Punjab, 5 from Sindh, 3 from North West Frontier Province and one from Balochistan. In 1949, the Basic Principles Committee submitted its report and recommended a federal democracy for the new nation. The members from Punjab objected that just because of being larger in number, Bengalis should not be allowed to have a dominant position (a similar stand taken by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1971 when he stated that the bastions of power are Punjab and Sindh). They probably had a different idea about parliamentary democracy. If this view is accepted then this means that ‘certain citizens are more equal than others’.19 Bengalis accepted the principle of parity in the legislature on the assumption that same will apply to Bengali representation in other areas including economic, civil service and military. Fearing the prospects of Bengalis joining hands with smaller provinces of the Western wing to press for their demands, Ayub Khan (who was C-in-C and also Defence Minister) came with the idea of ‘Unification of West Pakistan’ and initiated the process of merger of four provinces.20 After the 1958 coup, Ayub held the firm control and ran all affairs with the help of civilian bureaucracy. Ayub’s own hand picked cabinet members from East Pakistan (Muhammad Ibraheem, Abul Qasim Khan and Habib ur Rahman) demanded greater autonomy during discussions on Constitution and warned of grave dangers of a highly centralized government. Several 4:3 votes (there were four members from West Pakistan and three from Eastern wing) during these deliberations clearly indicated a genuine different thought process and different perspective among ministers from the two wings.21 Ayub’s response to the arguments of ministers from East Pakistan was that after the promulgation of the constitution, he dropped all three from the cabinet.22 This shows that Ayub kept these three Bengali ministers during the deliberations to show that the Bengali view was being considered while actually, he resented their views. As expected, the promulgation of 1962 Constitution resulted in massive protests in Eastern wing led by the students.

Similarly, economic issue was also a thorny one. The central government kept avoiding this on one or other pretext but was forced to address it as there was a unanimous consensus of Bengalis on the economic issue. In 1951, Sir Jeremy Reisman was invited to evaluate the existing allocation of revenues and recommend any changes. His recommendations were accepted as an Award. The results of this award gave credence to Bengali point of view. The revenue deficit of East Pakistan came to Rs. 7 million in 1952-53 from Rs. 40 million in 1951-52.23 The highly centralized rule of Ayub Khan further alienated the Bengalis as their representation in military and civilian bureaucracy was very low. The Bengali disaffection was obvious even to a blind man but the rulers chose to ignore it. In July 1961, Intelligence Bureau (IB) report about the feelings of Bengali population clearly stated that, “The people in this province will not be satisfied unless the Constitution ensures them in reality equal and effective participation in the management of the affairs of the country, equal share of development resources and, in particular, full control over the administration of this province. The intelligentsia would also like to see a directive principle in the Constitution to increase speedily East Pakistan’s share in the defence services as well as equal representation of East Pakistanis in the central services”.24 Alas, a mid-level police official of IB was more farsighted than the rulers of the country.

Face To Face

‘Does it not put you to shame that every bit of reasonable demand of East Pakistan has got to be secured from you at tremendous cost and after bitter struggle as if snatched from unwilling foreign rulers as reluctant concessions’. Awami League’s Leader Sheikh Mujeeb ur Rahman, 1966

1971 did not occur in a vacuum. It was the logical outcome of the trends, which were operational for at least few decades, and no attempt was made to address the fundamental issues. The initial Bengali attempts were to get their due share in the country’s decision-making process. It later evolved into Bengali nationalism and moved from greater autonomy to finally into struggle for complete independence. Every ill-thought step taken by the central government from banning the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore on national media to administrative and economic measures radicalized the Bengali population one step further. Even thirty years later, with all the hindsight, Pakistan is unable to comprehend the root causes of Bengali alienation. In 1998, a retired Lt. General is of the view that, “Bengali nationalism was only incidental, fostered by India to serve her purpose and larger interests in the region’.25 Major General (r) Rao Farman Ali (the political advisor of the military regime in East Pakistan and most informed person about the crisis) with all the hindsight has this to say about the landslide victory of Awami League in 1970 elections, “Total 37% votes were polled. Of this 20% were polled by Hindus from India, Awami League got 15% and Jamaat-e-Islami 2%”.26 Another commentator views the poor relations between Pakistan and Bangladesh due to the ‘stubbornness of Indian lobby in the bureaucracy of BD (Bangladesh)’ and this according to him is due to the ‘self-assigned objectives of keeping both the brothers apart’.27 Complete lack of understanding about the basic facts about their own society and paucity of information is quite evident from such assumptions.

Bengali politics was not monolithic. The Muslim League leadership consisted of landed elite and cosmopolitans from Calcutta. Later, vernacular leadership (Fazlul Haq and Maulana Abdul Hameed Bhashani) based on support from rural masses came to limelight. 1954 provincial elections were a watershed in the history of Pakistan. The United Front (consisting of Fazlul Haq’s Krishak Sramik Party and Suharwardy’s Awami League) swept the elections. United Front won 223 of the 237 Muslim seats and had many allies among the 72 non-Muslim elected members. Muslim League was wiped out of the East Bengal during this election. West Pakistani ruling elite’s apprehensions about the new Bengali leadership were re-enforced by the international politics and Pakistan’s attempts to join US sponsored military pacts against the Communism. Now a complex set of factors including domestic, personal and class interests, regional and international came into play which impacted the nascent democratic process of the new nation. When the defence treaty with United States was announced in February 1954, there was a general protest in East Bengal. Several demonstrations were held and newly elected assembly members signed a protest statement. This signature proved to be the death sentence of the provincial assembly. The ruling group in Karachi (Governor General Ghulam Muhammad, C-in-C General Ayub Khan and Defence Secretary Sikander Mirza) saw this situation as a grave threat to their vision for the country and future relationship with US, which would be a foundation stone of this policy. They concluded that to show to Washington that Pakistan was a serious ally and in full control of its house, East Pakistan’s political process has to be checked. On May 19, 1954, the mutual defence agreement was signed in Karachi between US and Pakistan and eleven days later, Governor General dismissed East Bengal Provincial Assembly on the flimsy charge that Fazlul Haq had uttered separatist words to Indian media. One day before the dismissal of the assembly, Pakistani Prime Minister while confiding with the US Charge, told him that Governor rule was planned for East Pakistan to route the communists. He revealed that the matter was not even discussed with the cabinet or Chief Ministers as information may be leaked to Peking and Moscow via Fazlul Haq.28 The central government sent two of its most notorious bureaucrats as Governor (Sikandar Mirza) and Chief Secretary (N.M. Khan) to East Pakistan to bring Bengalis in line. The plan was not for a short- term scuttling of the political process but a long-term as Ayub Khan confided with US ambassador. Pakistani decision makers always feel more at home with foreigners rather than their fellow countrymen. Ayub very candidly told the US ambassador that, “it would be necessary to keep military rule in effect in East Pakistan for a considerable length of time”.29

Ayub’s rule from 1958 to 1969 with banning of political activity and running of government through a strong central authority pushed Bengalis further in the background. The protests continue to simmer throughout this period, which finally exploded in Ayub’s face in 1969. By that time, Awami League under the leadership of Mujeeb was the dominant force. The major base of League’s support was in urban areas but Mujeeb was successful in getting the support of rural areas also, which markedly strengthened his position. The central government co-opted few Bengalis to give a facade of Bengali participation. Ministers and Governors belonging to East Pakistan held their offices at the pleasure of ruling elite. They had no popular base. Out of 16 East Pakistanis who served as ministers in Ayub government, 4 were from civil services and one journalist. The remaining 11 members were secondary leaders of Muslim League, 8 of whom had contested and lost the election of 1954 (the only election held in East Pakistan on the basis of adult franchise). The governor of East Pakistan, who held the office for seven long years, had lost so heavily in 1954 elections that his deposit was forfeited.30 This is the brief account of fundamental differences between the two wings which lasted for 24 years before the day of reckoning dawned in December 1971.

Dance of Death

The excesses committed during the unfortunate period are regrettable. General Pervez Musharraf writing in the visitors’ book at Savar Memorial for the Martyrs of 1971 in Dacca, July 2002 31

When Yahya Khan took control of the state in 1969, the country was effectively divided on all known fault lines. The separation between the two wings had been completed at the psychological level. The wisdom of Solomon was needed at that time to avoid a civil war but the only commodity in abundance was ignorance mixed with raw emotions and rhetoric. The military elite failed to understand the dynamics of their own society. They embarked on an ambitious but un-realistic goal of higher level of national cohesion in the absence of genuine participation. In March 1971, they took the fatal decision on the basis of their thoughts that the conflict is an artificial one and they will control it by attacking it directly and with brutal force. In this assumption, all the civilians of West Pakistan (including civilian bureaucracy and all political parties) were in agreement with the military’s point of view.

In the background of general mistrust and prejudice against Bengalis, when Bengali demands increased, so was the anger against them. The phenomenon was universal in West Pakistan affecting both civilians and army officers. By early 1971, there was a general consensus among the military leadership with probably very few exceptions (Lt. General Sahibzada Yaqub Khan was one) that the only solution left was the use of force. Yahya Khan called a meeting of Governors and Martial Law Administrators (MLAs) on February 22. Lt. General Yaqub Khan recalled the thought of Yahya Khan about use of strict measures. “He thought that a ‘whiff of the grapeshot’ would do the trick and reimposition of the rigours of martial law would create no problems”.32 To be fair to Yahya, he was not alone in this assessment. Almost all civil and military leadership was of the same view. To understand the decisions taken by the leadership, one has to understand the thinking of the senior officers at that time. Niazi explaining the apprehensions of West Pakistanis states, “They were also apprehensive about the Hindu influence on Bengali politics… The government would be formed by Bengalis, the iron fist in the velvet glove would be that of Hindus. To ensure that the Hindu was nullified, the parity system was evolved… This was aimed at protecting the interests of the West Pakistanis from exploitation by the Hindu-controlled Bengalis”.33 After the sweeping victory of Awami League in 1970, Yahya’s intelligence Chief, Major General Akbar Khan stated that, “we will not hand over power to these bastards”.34 In June 1971, in a divisional commander’s meeting, almost all generals disapproved negotiations with Awami League and stated, ‘we must finish this thing’.35 During a visit to Dacca during the March 1971 operation, a close associate of Yahya stated, “There can be no political settlement with the ‘Bingos’ till they are sorted out well and proper”.36 The civilians of West Pakistan in general had the same thinking. Bhutto had claimed that the bastions of power of Pakistan were Punjab and Sindh. The civil service held the general idea that, “a taste of the danda — the big stick — would cow down the Bengali babu’.37 The civilian bureaucrats serving the regime, like Information Secretary Roedad Khan were advising the generals about ‘putting some fear of God’ in Bengalis and how to purify Bengali race and culture by Arabising the Bengali script.38 The ruling elite was totally lost and the events were moving too fast for any of them to fully comprehend, let alone respond in any meaningful way. The rulers were now really suffering from delusions, unable to see beyond their boots. When the Bengali soldiers, police officials, diplomats and airline pilots were defecting en masse, the members of the regime were re-assuring the Pakistani envoys (Major General Ghulam Omar, Information Secretary Roedad Khan and Foreign Secretary Sultan Muhammad met with Pakistani envoys in Tehran and Geneva) that everything was under control and the majority of Bengalis were with Pakistan.39 This was being told when they could not get a single Bengali to work at Dacca radio station and in an ironic twist, Pakistani representative (Abu Saeed Chowdhry) attending a human right conference at Geneva had defected. They really thought that the world is blind.

This general thought process was not limited to only senior level. In soldier’s mind when conclusion was reached that Bengalis are traitors then the next line of action was quite obvious. You don’t negotiate with traitors, you finish them off to save the country from their ravages. Soldier was now ready, mentally prepared to deal with a group who was seen as coward and only to be dealt with force. A Pushtun ex-cavalry officer has eloquently expressed this thinking. During a conversation in early 1971, he dismissed Bengalis as cowards and predicted that they will run when first shot is fired. He confidently stated, “Do you know what an armoured regiment can do in Bengal? It will go through the Bengalis (he used the derogatory term ‘Bingo’) like a knife through the butter”.40 In March 1971, when the military action started, most officers and rank and file justified their actions on the basis of whatever seems plausible to them. At 16th Division HQ, Anthony Mascarenhas was told, “we are determined to cleanse East Pakistan once and for all of the threat of secession, even if it means killing off two million people and ruling the province as a colony for 30 years”.41 At 9th Division HQ at Comilla, Major Bashir justified the military action by stating that Bengali Muslims were “Hindu at heart” and this was a war between pure and impure. His superior Colonel Naim justified the killing of Hindu civilian population to prevent a Hindu take over of Bengali commerce and culture.42 A senior officer in Khulna told Maurice Quintance of Reuters, “It took me five days to get control of this area. We killed everyone who came in our way. We never bothered to count bodies”.43 Captain Chaudhry commented after the March operation that, “Bengalis have been sorted out well and proper — at least for a generation”. Major Malik agreeing with this assessment, remarked that, “Yes, they only know the language of force. Their history says so”.44

Secessions and civil wars are brutal and very violent. They run their course in a vicious cycle. The March 1971 military operation resulted in deaths of a large number of civilian Bengali operation. Bengalis being not in a position to tackle the well-organized army, turned their rage at the non-Bengali community amidst them. A vicious campaign of murder, rape and utter destruction was unleashed against the civilian non-Bengali population. These atrocities in turn brought the ire of the army, who simply went out of control in extracting a heavy price from the Bengalis for their rebellion. This orgy of bloodshed and outrageous atrocities against non-combatants is the most shameful and painful part of the collective history of the peoples of the two wings. Wanton murder committed by anybody should be condemned. It becomes critically important in case of organizations, which are held to higher standards than mobs. On Bengali side, some have given exaggerated accounts of atrocities, while on Pakistan side there has been total denial, which has resulted in much confusion. Now there is enough evidence to suggest that there was a planned and systematic killing of civilians, especially educated elite and Hindu civilians.45 Information provided by senior Pakistani officers points towards that. Niazi on his assumption of command in East Pakistan, issued a secret directive to all formations which stated, “Since my arrival, I have heard numerous reports of troops indulging in loot and arson, killing at random and without reason in areas cleared of the anti-state elements. Of late, there have been reports of rape… There is talk that looted material has been sent to West Pakistan through returning families”.46 A former Brigadier stated that Farman Ali was the principle architect of the plan to crush the Bengalis with force and was directly involved in the Hindu Basti massacre.47 Niazi also admits that a ‘scorched earth policy’ was carried by Tikka Khan and his orders of ‘I want the land and not the people’ was carried out in letter and spirit by Major General Framan and Brigadier Jehanzeb Arbab in Dhaka’. He also admitted that tanks and mortars were used against university students and 7th Brigade under Arbab not only killed people in Dacca but also resorted to looting banks and other places.48 The figures may be disputed by different parties but the fact remains that large scale death and destruction ensued since March 25 army operation. Enough information from Pakistani side and from Bengali side has emerged to support this conclusion.

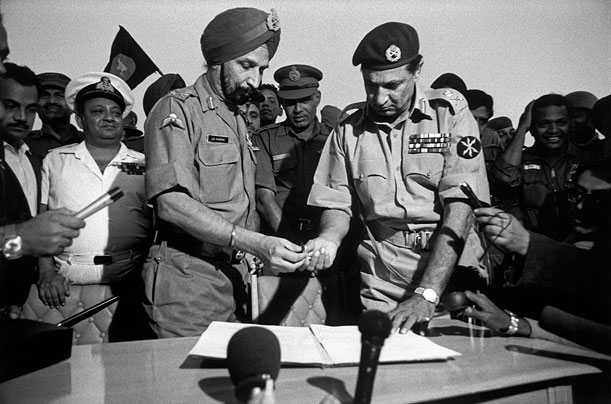

Military Aspect

The military by its nature is excessively sensitive to criticism, which makes the task of learning from its mistakes and inadequacies very difficult for it.49

The defence policy of Pakistan was shaped by small group of senior officers without any serious debate and discussion. The idea of ‘defence of East Pakistan from West Pakistan’ adopted by West Pakistan dominated senior military elites had its roots in the British traditions. The British C-in-C of Indian forces prior to partition, Field Marshal Claude Achinleck considered East Pakistan as ‘strategically useless’. This assertion was based on the observations that the country was flat and easy target for invasion, Bengalis had few martial traditions and the lands possessed few natural resources and no valuable industries. He, therefore, concluded that it was not prudent to invest in the defence of East Pakistan.50 In April 1947, Achinleck wrote about the defence concept of East Pakistan, “ the effort involved in providing adequate defence against aggression for this region would seem to be out of all proportion to its economic or strategic value”.51 From a colonial standpoint, this assessment may be correct but for an independent country to adopt such a policy of defence, where the region with majority population is considered useless, was simply absurd. By adopting this policy, essentially, one wing of the country was telling the other that ‘you are worthless and indefensible’, therefore we will allow the enemy to occupy your land and subjugate you while we defeat him somewhere else and then on the negotiating table we will try to win back your freedom. It will be very hard to find such an absurd examples in military history. Achinleck was highly regarded by almost all senior officers, many of whom had worked under him and his words and ideas were gospel truth. This one example shows the lack of independent thought and critical analysis among the senior officer corps regarding vital issues. Any serious discussion about this concept was discouraged by Ayub. (He wrote an angry letter to Prime Minister about the naval chief Vice Admiral H. M. S. Chaudhry and suggested his removal because he wanted to discuss this issue). In the absence of Bengali officers in the higher ranks, no one was there to challenge the idea and present an alternative view about defence of that area by someone who considered the area his homeland. At General Headquarters (GHQ), there was no well-thought out plan of how Pakistan will respond, if India attacked East Pakistan. With all the hindsight, a former Pakistani general in 2001 still insists that the policy of defence of East Pakistan from West Pakistan was a sound policy. The reason he gives is that West Pakistan was the ‘heartland’ and ‘hub of industrial and military power’.52 These esteemed and patriotic soldiers fail to understand the basic fact that no group of a country wants to see itself as ‘strategically useless’ or ‘gateway’ and hence dispensable while others elevating themselves to the ‘core’ and ‘heartland’ of the state worth fighting and dying for. 1965 war with India brought to open the hollowness of the idea of defence of East Pakistan from West Pakistan. On the Western front, the war was a stalemate despite better Pakistani equipment with no significant territorial gain. East Pakistan had only an under-strength division (14th Division commanded by Major General Fazal Muqeem Khan) and 15 Sabre jets. All communications between the two wings were cut off and East Pakistan was vulnerable. This heightened the sense of insecurity among the Bengalis along with the bitterness that they have been put at risk of Indian occupation to take Kashmir territory.53 The cost of 1965 war was not military but political. In my opinion, it was after the 1965 war that Bengalis in general started to question the viability of union of two wings under a single central government.

In early 1971, the rapidly deteriorating situation in East Pakistan forced the Pakistani GHQ to send two divisions (9th and 16th ) to the eastern wing. These two divisions were the strategic reserve of the country. Two more divisions were raised to replace the reserve divisions sent to East Pakistan. Thus, when the war came in November 1971, the strategic reserve divisions were in their infancy. ‘Pakistani GHQ had a naively simplistic attitude towards Bengali separatism. They did not realize that political problems could seriously compromise the strategic equilibrium of the army’.54 The military problems of East Pakistan had been clearly seen by US consular at Dacca as early as 1958, several months before the Ayub Khan’s coup. In his telegram to State Department on May 29, 1958, he wrote, “To hold East Pakistan, a dictator would have to strengthen army here, now one under-strength division, including two Bengali battalions which might mutiny. To strengthen army here means to weaken it in West Pakistan. Army here is thought capable of maintaining internal security, but this estimate is based on prospect of riots and local disturbances, not an open revolt aided in all likelihood by another country. Civil war is bitter and unrelenting as we know from our own experience and that of other countries”.55 Such foresight would be a very rare commodity in Pakistani leadership.

In a multi-ethnic state, the composition of the armed forces has both negative and positive impact on the society at large. This becomes especially important when military as an institution is involved in the direct running of the state as is the case of Pakistan. Pakistan army is the continuation of the army of the Raj. Both factors of low inclination of Bengalis towards soldiering and British theory of ‘Martial Races’ were responsible for almost no Bengali representation in the armed forces of Pakistan at the time of independence. In view of dominance of few ethnic groups in the military, it is viewed ‘as the instrument of specific regional interests’ and when armed forces assume the country’s leadership, this image is exacerbated.56 The country’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah ordered the raising of Bengali regiment. The first battalion of East Bengal Regiment (EBR) was raised in February 1948. It was popularly called Senior Tigers. The second battalion of EBR was raised in December 1948. This policy of incorporating the Bengalis was done half heartedly in the beginning as by 1968, there were only four Bengali regiments. There were several reasons for that. In a multi-ethnic society, where one dominant group defines the parameters of national security and proper code of patriotism, the group, which has different opinion, is seen as less ‘patriotic’. If the Bengali is less inclined to join the armed forces (which may have historical, social or cultural reasons), then it is assumed that he is less patriotic and his allegiance to the state is suspect. This will mean that he is not welcome in the institution when he decides to join. The general principle in this situation becomes that ‘groups that are less allegiant to the state or the regime have to be enlisted — but enlisted as late as possible and in such a fashion that the political cost is not intolerable for the elite’.57 This is exactly what Pakistani leadership did in case of Bengalis.

The British theory of Bengalis being non-Martial was also prevalent among the Punjabi and Pushtun officers (the dominant groups in Pakistan army). In Air Force and Navy, the numbers of Bengalis were steadily increased. There were several reasons for that. Compared to army, these two arms of armed forces are less politically involved in coups. Second, these two arms require more technical skills and higher education standards to run state of the art machines and Bengalis were able to perform these functions. In the military academy, Kakul, the Bengali cadets were considered inferior to the ‘Martial Races’. One former instructor at the academy in 1950s stated that Bengalis were generally given poor grades and seldom given any higher appointments. Many of them were shunted out as ‘Duds’.58 The gulf between Bengali and non-Bengali officers was as wide as between the general populations of the two wings. The total disregard of Bengali sentiments can be gauged by one incident which one Bengali cadet experienced during his stay at Kakul in 1970. At a dinner night, Major Shabbir Sharif (a good and well-respected officer of 6 Frontier Force Regiment who died in action in 1971 at Suleimanki sector) was sitting at the table with the Bengali cadet. He commented about the recent devastating cyclone in East Pakistan that more than hundred thousand people have perished. He then added that there were so many Bengalis that ‘I’m sure they will not be missed’. The young Bengali cadet was shocked to hear these words from an officer who was the role model for young cadets and everybody aspired to emulate him.59

In 1969, Yahya Khan ordered the raising of new Bengali regiments but like all other decisions it was too late. Bengalis have been too politicized and too alienated by that time. Compared to other regiments in West Pakistan, the EBRs were not mixed with other ethnic groups. The single class Bengali regiments assured that whenever the Bengali units decide to revolt, it will be en masse, and that is what happened in March 1971. Whenever a EBR revolted, the first thing they did was to kill their officers who were from West Pakistan. This would mean ‘no return’ for everybody and would keep even the reluctant ones in line. This is strangely reminiscent of the rebellion of the native sepoys of Indian Army in 1857. The Bengali officers and soldiers who were stationed in East Pakistan revolted en masses after the March 1971 operation and left with whatever equipment they could get their hands on. They later formed the core of Mukti Bahini. 1 EBR at Chandpur was significantly reduced in numbers. The regiment was moved to Jessore, where it was disarmed but some soldiers succeeded in escaping with arms. 2 EBR at Joydebpur rebelled on the night of March 28-29 and escaped with their arms and equipment. Two companies of 3 EBR at Ghoraghat and Gaibanda after rebellion moved to Hilli area. 4 EBR at Brahmanbaria and Shamshernagar after rebellion moved to Sylhet area to join rebels. The trainees at East Bengal Regimental Centre at Chittagong

(9 EBR was being raised at the time) rebelled on the night of March 25-26. There were also desertions in 10 EBR (another newly raised battalion which was National Service Battalion) while the remaining trainees were sent on leave. Of the total strength of 17,000 of the paramilitary force, East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), only 4,000 could be disarmed while the remaining decamped with their arms.60 Indian army organized the Bengali military, paramilitary and police personnel. The activities of the Mukti Bahini were code named “Operation Jackpot”. The country was divided into eight military sectors, each commanded by a Major, who had deserted from Pakistan Army. When India attacked East Pakistan, Bengali forces were organized into three brigades and attached to Indian forces in different sectors.61

There were about 28,000 Bengali armed forces personnel in West Pakistan. This group was caught in the middle of a very difficult situation. Some officers deserted and slipped into India. Pakistan army now was in a dilemma. It could not trust any Bengali officer but at the same time it could not act against anyone unless they have shown any sign of mutiny. The result was decisions, which were not practical. In one case, a Bengali officer was given the command of a platoon on the frontline where he will be charging the Indian forces but not given a personal weapon. When he asked about this unusual practice, the embarrassed commanding officer told him, “You have all the machine guns and anti-tank weapons under your command. Why do you need a personal weapon?”. He failed to give any reason of why all other non-Bengali officers of the regiment were keeping their personal weapons.62 After the ceasefire, they were imprisoned although they have not been guilty of any crime except being present at the wrong place at wrong time. They were later used as pawns in negotiations with India.

Strict adherence to professionalism and improved training with broader horizons for the senior brass are essential. Institutional control mechanisms should be in place to check any aberrant behaviour. Rhetoric, hyperbole and irrational thinking has no place in any institution let alone in the armed forces, which are involved in life and death situation. I’ll give few examples of the thinking of the senior brass regarding tactics and strategy and let the readers make the judgment. The commander of Eastern theatre, Lt. General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi’s plan which he presented to the central government in June 1971 (when he was facing a full blown rebellion of his own population with no heavy equipment and air force), in his own words was, “… I would capture Agartala and a big chunk of Assam, and develop multiple thrusts into Indian Bengal. We would cripple the economy of Calcutta by blowing up bridges and sinking boats and ships in Hoogly River and create panic amongst the civilians. One air raid on Calcutta would set a sea of humanity in motion to get out of Calcutta”.63 In summer of 1971, when Niazi was asked what will be his strategy in case of war, he had these words, which he uttered in the presence of senior military officers, “Have you not heard of the Niazi corridor theory? I will cross into India and march up the Ganges and capture Delhi and thus link up with Pakistan. This will be the corridor that will link East and West Pakistan. It was a corridor that the Quaid-e-Azam demanded and I will obtain it by force of arms”.64 A former Air Force Chief, Air Marshal Jamal Ahmad Khan while commenting about the pathetic performance of the air force in 1971, boasted that, “if India was not supported by Soviet Union, Pakistan Air Force would have crippled Indian air force”.65 These words are uttered by a former chief of air force in the presence of stark facts that Pakistan has evacuated all its fighter pilots (total of 14) from East Pakistan on December 8 and 9, seven days before the surrender as no airfield was functional. In the Western wing, air force was unable to give any meaningful support to the army or adequately protect its cities due to paucity of resources.66 Total lack of responsibility for one’s actions and severe compromise of professionalism of the senior brass due to involvement in non-military ventures is quite evident from this thinking.

The most difficult part in Pakistan is holding uniformed officers accountable for their acts of commission and omission. The severe decline in respect for army is the direct result of this approach where individuals are protected at the cost of the institution. The tragic part is that no one was held accountable let alone punished for the tragedy. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became the powerful chief executive of the country in the aftermath, therefore who was going to question him about his role? Many civilian bureaucrats close to regime enjoyed the same immunity. None of them felt any remorse or acknowledged even a grain of responsibility for their actions. Information Secretary of Yahya Khan, Mr. Roedad Khan continued to climb the ladders of promotions and retired with all perks and privileges from the senior most post. Mr. Ghulam Ishaque Khan weathered the socialism of Bhutto and Islamization of Zia very smoothly and ended up occupying the President House for quite a while. The military as institution also failed in this regard. Even if one accepts the notion that a particular individual has not committed any wrong, decency demands that in the wake of such a disaster, one should honourably leave the scene quietly and let others take charge. Rather than held accountable, many key players in 1971 tragic drama rose in ranks and held cushy appointments after retirement. Yahya Khan died while he was confined to his house. To his credit, when the time came to face the truth and informing the nation about ceasefire, he said, “The responsibility is mine and I am not going to shift it to anybody else. Whether it is popular or not, I will do it”.67 Chief of General Staff (CGS) Lt. General Gul Hassan became C-in-C for a while and after being fired from the post accepted the ambassadorial assignment in Austria. Air Force Chief Air Marshal Rahim Khan became ambassador to Greece. Lt. General Tikka Khan (the architect of Operation Searchlight in East Pakistan) rose to become Chief of Army Staff (COAS). Major General Rahim Khan (he was accused of deserting his command and escaping in a helicopter to Burma hours before surrender at Dacca) became CGS after his return from Burma. After retirement, he served as Defence Secretary and later Chairman of Pakistan International Airline. Major General Rao Farman Ali (Political advisor of the regime in East Pakistan) became Managing Director of Fauji Foundation. He also served in the election cell set up by General Zia in July 1977, to utilize his skills of political manoeuvring which he had sharpened in East Pakistan. Director General of Inter Services Intelligence (DG ISI) Major General Akbar Khan served as High Commissioner to United Kingdom. Director General of Military Intelligence (DG MI) Major General Iqbal Khan rose to become a four star general and Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (JCSC). Major General Ghulam Omar (Secretary of National Security Council) served as Chairman of National Language Authority after retirement. Director General Military Operations (DGMO) Major General Majeed Malik was promoted to Lt. General. After retirement, he served as ambassador to Morocco and later Minister of Kashmir Affairs. Lt. General Niazi states that he sent back Brigadier Jahanzeb Arbab to West Pakistan on charges of corruption.68 Arbab rose to become Lt. General, Corps Commander and Governor of Sindh province. After retirement, he served as ambassador to United Arab Emirates. Niazi after his release from India, became a politician for a while and started to address public rallies. The in charge of Khulna Naval Base, Commander Gul Zareen took a gunboat and escaped towards sea, where he was picked by a foreign ship. This occurred on December 7, nine days before the surrender. It is not known what action, if any, was taken against this officer.

General Musharraf’s comments about accountability of officers accused of misconduct in 1971 is not correct. He stated, “It was a tragic part of our history but the nation should move forward rather than living in the past. We should leave the matter to history. As a Pakistani, I would like to forget 1971’.69 If the nation forgets 1971, it is more likely that the mistakes will be repeated. Many actors of 1971 have died. It is the moral duty of those who are living to honestly admit about their role. The duty of a soldier in this regard is critical to rehabilitate the image of the institution. Admitting one’s mistake is a sign of greatness and not weakness. In the strict legal sense, everybody is innocent as no one has been tried in a competent court of law and convicted. There are more higher values, which need to be upheld. The code of conduct of a soldier and moral law necessitates that those individuals who are still alive should come up with the truth rather than attempting to save their distorted sense of ‘honour’.

Conclusion

In a multi-ethnic society like Pakistan, where all ethnic groups are not represented in the institution of armed forces can result in a very complicated situation when army takes control of the state. The military’s ‘seizure of power have the effect of ethnicization of areas of politics not formerly ethnically salient and/or intensifying ethnic awareness where it already exists’.70 This is a prelude to a violent showdown between the state and the aggrieved ethnic group. The country has seen this with Bengalis, Baluchs, Sindhis and Muhajirs. The success of Bengali nationalism ‘with direct Indian intervention, was the most extreme example of the links between domestic repression, regional intervention and extra-regional competition’.71

The social problems of Pakistan are multi-factorial and need a long term planning and working. If past is any guiding light, it amply teaches us that the solution to present dilemma is a representative form of government, where every member of the federation feels that it is part of the decision-making process. The participation at grass-root level of local representatives to address their problems is critical. Just a symbolic figurehead of the government from a minority ethnic group would not solve the problem. Until this fact is brought home to the ruling groups, the central authority of the state will be in permanent conflict with one or the other group in the periphery, keeping the state off balance perpetually. It should be remembered that, ‘it is the dominant elite’s own goals and behaviour that threaten to bring about disintegration’.72 If Hamood-ur-Rahman Commission was published thirty years ago, the nation would have closed that chapter. The reason of opening of old wounds thirty years later is the tragic fact that the nation and its leaders refuse to face the facts. As a nation, the first step for Pakistan is to admit its mistakes and tender apology to Bengalis for the conduct in 1971. For a fresh start, it is essential that all skeletons in the closets should be taken out. Unless, all old demons are taken out from darkness and exorcised, they will keep haunting the nation forever.

Neither to laugh, nor cry, just to understand — Spinoza

Notes

1Amin, A. H. The Western Theatre in 1971 — A Strategic and Operational Analysis. Defence Journal (Karachi. Online Edition. All further references are from online edition), February 2002

2Binder, Leonard. Islam, Ethnicity, and the State in Pakistan in Banuazizi, Ali and Weiner, Myron (Ed.) The State, Religion and Ethnic Politics: Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan (Lahore: Vanguard Books, 1987), p. 265

3Hussain, Asaf. Ethnicity, Identity and Praetorianism in Pakistan. Asian Survey, Vol. XVI; No: 10, October 1976, p. 925

4Ali, Mahmud. The Fearful State (London: Zed Books, 1993), p. 252

5Ibid, p. 249

6Von Vorys, Karl. Political Development in Pakistan, (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1965)p. 155

7Murshid, M. Tazeen. A House Divided: The Muslim Intelligentsia of Bengal in Low A. Donald (Ed.) The Political Inheritance of Pakistan (London: MacMillan, 1991), p. 147

8Metcalf, Barbara D. & Metcalf, Thomas R. A Concise History of India, p. 111

9Rahman, Hafizur. Why was Bengal Ignored? The News (Lahore. Internet Edition), February 17, 2001

10Murshid, Tazeen. A House Divided, p. 159

11Talbot, Ian. Pakistan: A Short History (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), p. 24-25

12McGrath, Allen. The Destruction of Democracy in Pakistan (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 4-5

13Baxter, Craig. Bangladesh: From Nation to a State (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1997), p. 72

14Murshid, Tazeen. A House Divided, p. 159

15Talbot, Ian. Pakistan, p. 163

16Zaheer, Hassan. The Separation of East Pakistan (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 24

17Murshid, Tazeen. A House Divided, p. 165

18Zaheer. The Separation, p. 26

19Jafferlot, Christopher. Nationalism Without a Nation: Pakistan Searching for its Identity (London: Zed Books, 2002), p. 18

20Zaheer. The Separation, p. 38

21Von Vorys, Karl. Political Development in Pakistan, p. 218

22Gauhar, Altaf. Ayub Khan: Pakistan’s First Military Ruler (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 100-101

23Budget Speech of Finance Minister in Constituent Assembly (Legislature) of Pakistan Debates (CALD), Vol. 1; No:2 (15 March 1952), p. 44 cited in Hasan, Zaheer. The Separation, p. 51

24Gauhar, Altaf. Ayub Khan, p. 98-99

25Lodhi, Sardar F. S. Lt. General (r). Security Concerns of Pakistan. Defence Journal, December 1998

26Salasal, Jalees. Court Martial, p. 232

27Siddique, A. Pak-Bangladesh Relations. The Nation (Lahore: Online Edition. All further references from online edition)), August 03, 2002

28Prime Minister’s meeting with US Charge, Emmerson on May 29, 1954 in Karachi. Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS). 1952-1954 Volume XI. Department of State Publication 9281 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), p. 1864, hereafter referred as FRUS

29The ambassador in Pakistan (Hildreth) to Department of State on subject of conversation with General Ayub Khan on July 15, 1954 (Secret). FRUS, p. 1856

30Maniruzzaman, Talukdar. Group Interests and Political Change: Studies of Pakistan and Bangladesh (New Delhi: South Asian Publishers, 1982), p. 86

31The Nation, July 30, 2002

32Lt. General Sahibzada Yaqub Khan’s conversation with Hasan Zaheer in Zaheer, Hasan. The Separation, p. 141

33Niazi, Amir Abdullah Khan. Lt. General (r). The Betrayal of East Pakistan (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 34

34Interview of Major General Rao Farman Ali who was present in that meeting cited in Hassan, Ali. Pakistan: Generals aur Siyasat, Urdu (Pakistan: Generals and Politics) (Lahore: Vanguard Books, 1991), p. 167

35Major General M. I. Karim’s account of the meeting in Zaheer, Hasan. The Separation, p. 346

36Salik, Siddique. Witness to Surrender (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1977), p. 107

37Akhund, Iqbal. Memoirs of a Bystander (Karachi: Oxford University Press, ), p. 211

38Siddiqi, A. R. Brigadier (r). Military in Pakistan: Image and Reality (Lahore: Vanguard Books, 1996), p. 195

39Zaheer. The Separation, p. 310-311

40Akbar, Ahmad S. Pakistan, Jinnah and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin (London: Routledge, 1997), p. 238

41Mascarenhas, Anthony. The Rape of Bangladesh (Delhi: Vikas Publications, 1971), p. 117

42Loshak, David. Pakistan Crisis (New York: McGraw Hills Book Company, 1971), p. 112

43Ibid, p. 108

44Salik. Witness, p. 78

45For details of eyewitness accounts of killing of Bengali university professors, see Malik, Amita. The Year of Vulture (New Delhi: Orient Longman Ltd., 1972), p. 75-77 and Kabir, Mafizullah. Experience of an Exile at Home: Life in Occupied Bangladesh (Dacca: Asiatic Press, 1972), p. 35, 40 & 41

46Confidential instructions sent from HQ Eastern Command to formations dated April 15, 1971, provided by Niazi to his interviewer cited in Salasal, Jalees. Court Martial, p. 187

47Ali, F. B. Brigadier (r). Good, Decent Men, But… The Frontier Post (Peshawar. Online Edition), August 25, 2000

48Niazi. The Betrayal, p. 46 & Herald (Karachi), September 2000, p. 29

49Masood, Talat. Lt. General (r). Pitfalls of the Military’s Over-Stretch. Dawn (Karachi. Online Edition), August 20, 2001

50‘The Military Implications of Pakistan’, memorandum by Claude Achinleck attached to a letter from Achinleck to Mountbatten, 24 April 1947, Jonh Ryland’s University Library of Manchester, Achinleck MSS, File 76, No:1224b, 2 cited in Wainwright, Martin A. Inheritance of Empire: Britain, India, and the balance of power in Asia, 1938-55 (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1994), p. 74

51Hamid, Shahid. Major General (r). Disastrous Twilight, Appendix IX, p. 335

52Arif, Khalid M. General (r). Khaki Shadows: Pakistan 1947-1997 (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 125

53Jahan, Rounaq. Pakistan: Failure in National Integration (New York & London: Columbia University Press, 1972), p. 166-67

54Amin. The Western Theatre

55FRUS. Publication 1996, p. 649-50

56Malik, Iftikhar H. State and Civil Society in Pakistan: Politics of Authority, Ideology and Ethnicity (Lahore: M. Anwar Iqbal for MacMillan Publishers, 1997) p. 79

57Enloe, Cynthia. Ethnic Soldiers: State Security in Divided Societies (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1980), p. 52

58Malik, Tajjamal Hussain. Major General (r). The Story of My Struggle (Lahore: Jang Publishers, 1992, Second Edition), p. 29

59Author’s interview with a former Bengali officer of Pakistan army, October 2002

60Zaheer. The Separation, p. 169-70

61Heitzman, James & Worden, Robert L. (Ed.) Bangladesh: A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1989), p. 209-211)

62Author’s interview with a former Bengali officer of Pakistan army, October 2002

63Niazi. Betrayal of East Pakistan, p. 66

64Akbar, Ahmad. Pakistan, Jinnah, p. 239

65Interview with Air Marshal Jamal Ahmad Khan in Salasal, Jalees. Court Martial (Urdu) (Karachi: Al-Jalees Overseas Publishing Svc., 1999), p. 218

66Indian jets had attacked oil refinery in Karachi and sent sorties to different cities. On Sindh border, Indian pilots had a field day of target practice, where half of a tank regiment (22 tanks) was knocked out of action.

67Zaheer. The Separation, p. 424

68Herald, September 2000, p. 29

69The Nation, September 12, 2000

70Enloe, Cynthia. Ethnic Soldiers, p. 129

71Ali, Mahmud. The Fearful State, p. 14

72Ibid, p. 252