An Imaginary meeting..

By Pakistani-American writer Asif Ismael.

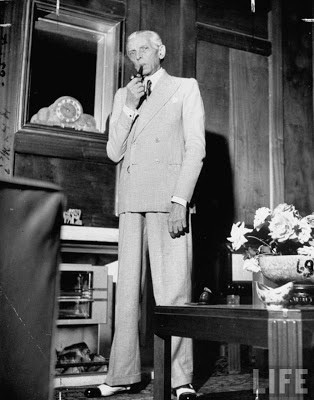

“Didn’t I tell you, sir, this idea of yours: a separate homeland for the Muslims, is a bit fanciful? And you continued to press me to come to Bombay.” Jinnah said, arranging the crease of his pants over his knees. Through a slit in the curtains hanging behind his host’s back, a sunbeam streamed into the room and fell on the silver base of a hooka placed next to his feet–its reflection distorted in his impeccably shined black shoe. He sat on the rocking chair stiff as a board, for even a slight movement made the chair squeak.

His host, Iqbal, lying down on his side in a four-post bed, had his temple glued to his fist: a man in deep thought–a posture imprinted on the minds of the masses–the bed-sheet crumpled around the point of Iqbal’s elbow.

Iqbal, for the last several minutes, had been staring at the floor, lost in thought. Actually he’d been marvelling at Jinnah’s shoes, glistening, on his Isfahan, planted firmly, an inch or two apart, one slightly ahead of the other, but not too far ahead, reflecting a certain precision which his poetic sensibility had found challenging to grasp.

“Look, it’s not over yet,” Iqbal said. He closed his eyes, grabbed his hooka pipe and began inhaling through his fingers clenched around the tip. The embers turned crimson within the bowl. The room smelled of imported tobacco. The toking filled the room with gurgles.

Jinnah’s lips quivered without emitting a sound as he tried talking through the loud and prolonged guggle of the hooka; then pressing them together he waited for the old man to finish his noisy inhale. The gurgling stopped followed by a spell of raspy cough that brought the host’s eyes to tears. Raising his eyebrows Jinnah took a deep breath, like a sigh, and holding it in his chest he waited for the cough to subside. And when it did and as he slowly exhaled the trapped air in his chest, he noticed drops of tears rolling down on Iqbal’s cheeks. The smoke, the swirling blue haze caught in the sunbeam over the head of his host, thrown in turmoil when touched by his breath. He decided to stay quiet.

A man in his twenties, his hair held in a ponytail, appeared at the door holding a pigeon, white as snow. He held the bird next to his chest, petting it. “Allama Ji, today is the day, when the whole town will know what kind of pigeons we breed here in Mohalla Kashmarian,” he said. He stopped in his tracks at the door upon noticing the stare of Jinnah. He was unsure, though, if those two arrows of steel were directed at him or at the pigeon.

“Oh, don’t mind this chap: He’s my pigeon breeder, the best in Punjab,” Iqbal said, clearing his throat.

“I’d better be going–I’ll have to catch the train early in the morning from Lahore. Meetings and more meetings!–I wonder when this will end, if ever,” Jinnah said, getting up. “Think about what I’ve said. Have a nice Pigeon Day.” Putting his black overcoat on, he glanced at the pigeon breeder who stood in the doorway lost in his world, his eyes on the pigeon, petting it softly. Jinnah put his hat on, shrugged his shoulder to ease them into his coat, and left the room.

“Allama Ji, is he the only one you’ve been able to find in the whole world to lead the Muslims of India? Sometimes, you seriously make me wonder, Allama Ji,” the pigeon breeder said, sitting on the rocking chair where Jinnah had sat. The pigeon emitted a squeal.

“Oh Bashir, my son, you’re too innocent–To win you must find the best of the breed. When the pigeon is flying high, looking like a dot, darting across the vast blue sky, who cares if it has been bred in Sailkot, Daska, Lahore, London, Paris or New York,” Iqbal said, getting off from the bed and sliding his feet into a pair of slippers. “Lets go to the rooftop.”

“Allama Ji, hurry up! Wearing a yellow shawl bright as sun, she’s been waiting for you on her rooftop,” Bashir said. “I’m going to carry your hooka. How about some daaroo?”

“Oh Bashir, you are a bastard of the highest order. Don’t you see the sun is still way too high? Do you want me to see four pigeons flying in the sky, instead of two?” Iqbal said, taking the bird from him. The pigeon fluttered a bit before settling in a new set of hands. “What a beauty! Look at her eyes! Wells filled with water sweet and pure; the delicate nose, the straight neck putting even a shaheen to shame!”

“Today’s the day, when the pigeons fly high–when the eyes meet across the sky; when love fills the old boot; and water rises in the new shoot,” Bashir said, stepping behind Iqbal on the stairway.

“Okay! Okay! just get the damn daaroo,” Iqbal said, turning around. He looked up and said: “The wind blows lifting the yellow sand off the golden dunes, carrying the musk of the beloved.”

From the rooftop they both saw Jinnah, hunched like a bow, getting his skinny frame into his black Bentley, his chauffeur standing stiff holding the car’s door open for him. A gang of kids availing this godsent opportunity of putting their hands on such a shiny creature, had touched the car to their heart’s content, leaving streaks of dirt in the spotless glimmer of its black armor.

With one foot in the car, Jinnah turned around as if he felt their gaze on his back. He looked up for an instant, and saw Iqbal and his pigeon breeder standing at the rooftop. They waved at him, smiling. Shaking his head he slid into his car. The driver shut the door softly and yelled at the kids already planning to run behind this sleek creature that looked so foreign and new in their old Mohalla Kashmarian.

Inside, the car smelled of tanned hide, tobacco, English tweed, and dog.