….The Pushtuns are

divided among the Durrani, Ghilzai, Waziri, Khattak, Afridi, Mohmand,

Yusufzai, Shinwari….. each tribe is divided into subtribes…..divided into numerous

clans… Zahir Shah belongs to the Muhammadzai clan of the Barakzai subtribe of the Durrani

tribe. Such clan, subtribal, and tribal divisions contribute already

intense rivalries and divisions…..

…

For some time now there has been an expectation that post-2014 Af-Pak will go from a slow burning play-field to a hot fire battlefield. These fears are just a tiny bit less now that Ashraf Ghani has assumed powers (by consensus) and Americans are allowed to stay and fight (and contribute to the Afghan economy), unlike Iraq.

Traditionally we have had a lot of (gleeful) finger pointing from the left that if the world had simply ignored their attempt to transform Afghanistan into Cuba then things would have been just fine and dandy. The problem though is more basic: Pashtuns have never accepted the Durand line and the attraction for a national homeland (we would presume) would be just as strong as that of the Sikhs (and Kashmiris and Balochis…).

The difference between then and now is that the Pashtun powers that be now feel confident about their chances to create Pakistan in their own image. All the Taliban versions (Punjabi, Pashtun) may have differences in goals and opinions but doctrinally (and often operationally) they are brothers.

We have seen this Punjabi vs. Pashtun movie before when Afghan armies would raid Lahore and Delhi and Punjabi armies would go the other way. But we have not really seen a joint Punjabi-Pashtun operation to make Pakistan more pure and homogeneous.

The fear is not that the tribal districts will be ruled by religious nut-jobs (they already do), the worry is that Karachi and Lahore will fall in the hands of the extremists. This will happen as part of a well co-ordinated strategy. These people know what they are doing and they are capable of playing the long game.

In this context meaningless words like “failed state” are not helpful, a state bound by powerful (but hateful) laws is not the same as a law-less state. The far greater problem may be “isolated state.” People – yes, lots of Hindus, Jews and Americans, but also Europeans and Chinese…and Arabs (!!!) – associating Pakistan with terrorism when it is actually Pashtun nationalism in alliance with Punjabi islamism hoping to create a Caliphate for the true believers, trying to establish territorial, cultural, and spiritual control through the power of the gun (and the mob).

…….

Flying into Kabul earlier this week just before Afghanistan’s

presidential inauguration, a number of embassy cars sat waiting to pick

up VIPs and visitors from their respective nations. It was telling that

the Pakistani embassy cars were the only ones not armored.

….

After all,

because Pakistan supports the Taliban and its terrorism, the visitors

from Islamabad had about as much need for an armored car as Iranian

diplomats would in Hezbollah-controlled southern Lebanon. Terrorism is

not a random phenomenon.

…

For many Americans, ancient history is

anything more than a decade or two old. While a generation of American

servicemen, diplomats, and journalists think about the border between

Afghanistan and Pakistan, they think about it in terms of one-way

infiltration: Pakistani-supported Taliban or other terrorists

infiltrating into Pakistan in order to conduct terrorism. In this, they

are not wrong. But if the broader sweep of history is considered, then

much of the infiltration went the other way, with Afghan and Pashtun

nationalists sneaking across the border into Pakistan’s Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa, formerly known as the Northwest Frontier Province. (I had

summed up a lot of that history, here.)

…

As U.S. forces and America’s NATO partners prepare to withdraw upon

an arbitrary political deadline, terrorism will surge inside Afghanistan

but terrorism will not be limited to that country. Many Afghans

believe—and they are perhaps not wrong—that diplomacy will never

convince Pakistan to curtail its terror sponsorship. Pakistani officials

do not take American diplomats seriously. Pakistani diplomats either

lie shamelessly or purposely keep themselves ignorant of the actions and

policies of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Instead,

Afghans may increasingly turn to tit-for-tat terrorism, all with

plausible deniability: A bomb goes off in Kabul? Well, then a bomb will

go off in Islamabad. A Talib shoots an Afghan colonel? Well, then a

Pakistani colonel will mysteriously suffer the same fate.

…

Pakistan has supported Islamist radicalism since at least 1971, when

its defeat at the hands of Bangladeshi nationalists convinced the ISI

and President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto that radical Islam could be the glue

that held Pakistan together and protect it against the corrosiveness of

ethnic nationalism. President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq took that embrace of

Islamism to a new level.

….

The Pakistani elite has not hesitated to use the Taliban and various

Kashmiri and other jihadi and terrorist groups as a tool of what it

perceives as Pakistani interests. Sitting within their elite bubble,

they mistakenly believe that they can control these forces of radical

Islamism. That Pakistan has suffered 50,000 deaths in its own fight

against radicals suggests they are wrong. The blowback may only have

just begun, however.

….

Pakistanis may believe that an American withdrawal will bring peace

(on Pakistan’s terms) to Afghanistan, but they may soon learn the hard

way that Afghanistan can be an independent actor; that not every

official is under the control of, let alone easily intimidated by

Pakistan; and that terrorism can go both ways. That is not to endorse

terrorism—analysis is not advocacy—but simply a recognition that the

regional reverberations of the forthcoming American and NATO drawdown

will be far broader than perhaps both Washington and Islamabad consider.

….

As the United States prepared for war against Afghanistan, some

academics or journalists argued that Usama bin Ladin’s al-Qa’ida group

and Afghanistan’s Taliban government were really creations of American

policy run amok. A pervasive myth exists that the United States was

complicit for allegedly training Usama bin Ladin and the Taliban.

…

For

example, Jeffrey Sommers, a professor in Georgia, has repeatedly claimed

that the Taliban had turned on “their previous benefactor.” David

Gibbs, a political science professor at the University of Arizona, made

similar claims. Robert Fisk, widely-read Middle East correspondent for

The Independent, wrote of “CIA camps in which the Americans once trained

Mr. bin Ladin’s fellow guerrillas.”(1) Associated Press writer Mort

Rosenblum declared that “Usama bin Ladin was the type of Soviet-hating

freedom fighter that U.S. officials applauded when the world looked a

little different.”(2)

…

In fact, neither bin Ladin nor Taliban spiritual leader Mullah Umar

were direct products of the CIA. The roots of the Afghan civil war and

the country’s subsequent transformation into a safe-haven for the

world’s most destructive terror network is a far more complex story, one

that begins in the decades prior to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

…

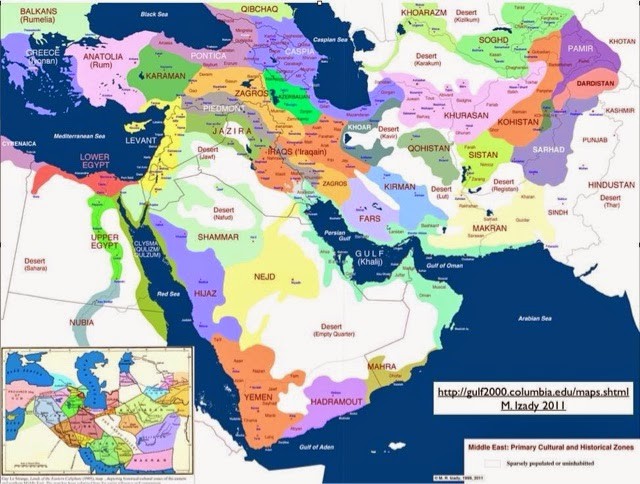

THE CURSE OF AFGHAN DIVERSITY

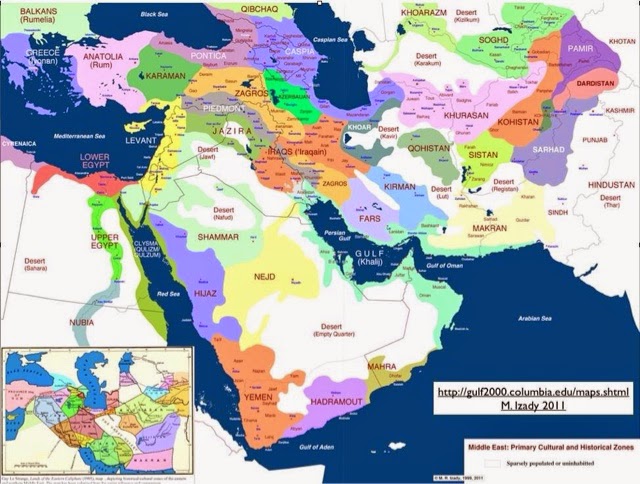

Afghanistan’s shifting alliances and factions are intertwined with

its diversity, though ethnic, linguistic, or tribal variation alone does

not entirely explain these internecine struggles. Afghanistan in its

modern form was shaped by the nineteenth-century competition between the

British, Russian, and Persian empires for supremacy in the region. The

1907 Anglo-Russian Convention that formally ended this “Great Game”

finalized Afghanistan’s role as a buffer between the Russian Empire’s

holdings in Central Asia, and the British Empire’s holdings in India.

…

The resulting Kingdom of Afghanistan was and remains ethnically,

linguistically, and religiously diverse. Today, Pushtuns are the largest

ethnic group within the country, but they represent only 38 percent of

the population. An almost equal number of Pushtuns live across the

border in Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province. Ethnic Tajiks comprise

one-quarter of the population. The Hazaras, who generally inhabit the

center of the country, represent another 19 percent. Other groups —

such as the Aimaks, Turkmen, Baluch, Uzbek, and others comprise the

rest.(3)

…

Linguistic divisions parallel, and in some cases, overlap ethnic

divisions. In addition to Dari (the Afghan dialect of Persian that is

the lingua franca of half the population) and the Pushtun’s own Pashtu,

approximately ten percent of the population speaks Turkic languages like

Uzbek or Turkmen. Several dozen more regional languages exist.(4)

…

Tribal divisions further compound the Afghan vortex. The Pushtuns are

divided among the Durrani, Ghilzai, Waziri, Khattak, Afridi, Mohmand,

Yusufzai, Shinwari, and numerous smaller tribes. In turn, each of these

tribes is divided into subtribes. For example, the Durrani are divided

into seven sub-groups: the Popalzai, Barakzai, Alizai, Nurzai, Ishakzai,

Achakzai, and Alikozai. These, in turn, are divided into numerous

clans.(5) Zahir Shah, ruler of Afghanistan between 1933 and 1973,

belongs to the Muhammadzai clan of the Barakzai subtribe of the Durrani

tribe. Such clan, subtribal, and tribal divisions contribute already

intense rivalries and divisions.

…

Religious diversity further complicated internal Afghan politics and

relations with neighbors. Once home to thriving Hindu, Sikh, and Jewish

communities as recently as the mid-twentieth century, Afghanistan today

is overwhelmingly Muslim. The vast majority — 84 percent — are Sunni

Muslims. However, the Hazaras are Twelver Shi’i, and so have sixty

million co-religionists in Iran. In the northeastern Badakhshan region

of Afghanistan, there are many Isma’ili Shi’ia. When I traveled along

the Tajik-Afghan frontier in 1997, numerous Tajik villagers told me they

had regular clandestine contacts with the Isma’ili communities “just

across the river,” despite the watchful guard of the Russian 201st

brigade.

Many countries thrive on diversity. However, in the context of both

Afghanistan and the civil war, the fact that most identifiable Afghan

groups have co-linguists, co-ethnics, or co-religionists across national

boundaries became a catalyst for the nation’s collapse, as well as a

major determinant in the coalition-building during both the years of

Soviet occupation and post-liberation struggle. For example, the

Pushtuns of Kandahar have traditionally looked eastward toward their

compatriots in Pakistan, while the Persian-speakers of Herat have looked

westward into Iran. Uzbeks in Mazar-i Sharif have more in common with

their co-linguists in Uzbekistan than they have with their compatriots

in Kandahar.

As various Afghan constituencies looked toward their patrons across

Afghanistan’s frontiers for support, they created an incentive for

Afghanistan’s neighbors to involve themselves in internal Afghan

affairs. The blame cannot be placed only on outside interference in

Afghanistan, though, for the Afghan government has a long though often

forgotten history of interfering with the ethnic minorities in

surrounding countries and especially Pakistan.

DOWN THE SLIPPERY SLOPE

Zahir Shah took the throne of Afghanistan in 1933 after the

assassination of his father, Nadir Shah. Zahir was not a strong leader,

though. As Louis Dupree, the preeminent anthropologist of Afghanistan

observed, “King Mohammed Zahir Shah reigned but did not rule for twenty

years.”(6) Instead, real power remained vested in his uncles who sought

to break Afghanistan out of both its isolation and dependence on either

the Soviet Union or Great Britain. It was during this period that

Afghanistan and the United States first exchanged ambassadors. The

Afghan government awarded a San Francisco-based engineering firm the

rights to develop hydroelectric and irrigation projects in the Hilmand

River Valley. Slowly, Afghanistan began drifting toward the West, both

politically and economically.

In 1953, Zahir Shah’s first cousin, the 43-year-old Muhammad Daoud

Khan became prime minister. Daoud sought to root out graft in the huge

Hilmand scheme, speed up reforms, but he remained a firm opponent of the

liberalization in Afghan society. Seeking to recalibrate Afghanistan’s

neutrality, Daoud sought closer relations with the Soviet Union.(7)

However, neutrality in the Cold War was a fleeting phenomenon.

Both the Soviet Union and the United States increasingly plied

Afghanistan with economic and technical assistance. Daoud’s government

sought to buy arms, and approached the United States several times

between 1953 and 1955. However he was unable to come to an agreement

with Washington, which tied arms sales to either membership in the

anti-Communist Baghdad Pact or at least in a Mutual Security Pact.(8)

The Soviet Union, though, was eager to supply what the United States

would not. In 1956, Afghanistan purchased $25 million in tanks,

airplanes, helicopters, and small arms from the Soviet bloc, while

Soviet experts helped construct or convert to military specifications

airfields in northern Afghanistan. The Cold War had come to Afghanistan.

While acceleration of the Cold War competition in Afghanistan — with

its subsequent tragic impact on the country — would be a major legacy

of Daoud, it would not be his most important one. Rather, during Daoud’s

premiership Afghanistan’s relations with neighboring Pakistan would

irreversibly sour. Afghanistan increasingly saw in Pakistan both a

competitor and a threat. Indeed, Daoud’s quest for arms was in large

part motivated by Afghanistan’s own cold war with Pakistan. However, it

was Daoud’s support for a Pushtun nationalist movement in Pakistan that

would have the greatest lasting repercussions.

THE QUESTION OF GREATER PUSHTUNISTAN

The root of the Pushtunistan problem begins in 1893. It was in that

year that Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, foreign secretary of India,

demarcated what became known as the Durand line, setting the boundary

between British India and Afghanistan, and in the process dividing the

Pushtun tribes into two countries.

The status quo continued until 1947, when the British granted both

India and Pakistan their independence. Afghanistan (and many Pushtuns in

Pakistan) argued that if Pakistan could be independent from India, then

the Pushtun areas of Pakistan should likewise have the option for

independence as an entity to be called “Pushtunistan,” or “land of the

Pushtun.”(9) Once independent of Pakistan, Pushtunistan would presumably

choose to unite with the Pushtun-dominated Afghanistan, to form a

“Greater Pushtunistan” (and also bolster the proportion of Pushtuns

within Afghanistan).

The Pushtunistan issue continued to simmer into the 1950s, with

Afghanistan-based Pushtuns crossing the Durand Line in 1950 and 1951 in

order to raise Pushtunistan flags. Daoud, prime minister from 1953 to

1963, supported the Pushtun claims. The issue soon became caught up in

Cold War rivalry. As Pakistan ensconced itself more firmly in the

American camp, the Soviet Union increasingly supported Afghanistan’s

Pushtunistan agitations.(10)

In 1955, Pakistan reordered its administrative structure to merge all

provinces in West Pakistan into a single unit. While this helped

rectify, at least in theory, the power discrepancy between West and East

Pakistan (the latter of which became Bangladesh in 1971), Daoud

interpreted the move as an attempt to absorb and marginalize the

Pushtuns of the Northwest Frontier Province. In March 1955, mobs

attacked Pakistan’s embassy in Kabul, and ransacked the Pakistani

consulates in Jalalabad and Kandahar. Pakistani mobs retaliated by

sacking the Afghan consulate in Peshawar. Afghanistan mobilized its

reserves for war. Kabul and Islamabad agreed to submit their complaints

to an arbitration commission consisting of representatives from Egypt,

Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey. Arbitration failed, but the

process provided time for tempers to cool.(11)

Twice, in 1960 and in 1961, Daoud sent Afghan troops into Pakistan’s

Northwest Frontier Province. In September 1961, Kabul and Islamabad

severed diplomatic relations and Pakistan attempted to seal its border

with Afghanistan. The Soviet Union was more than happy to provide an

outlet, though, for Afghanistan’s agricultural exports, which the

Soviets airlifted out from the Kabul airport. Between October and

November 1961, 13 Soviet aircraft departed Kabul daily, transporting

more than 100 tons of Afghan grapes.(12) The New Republic commented,

“The Soviet Government does not intend to miss any opportunity to

increase its leverage.” Indeed, not only did the Soviet Union “save” the

Afghan harvest, but Pakistan’s blockade also effectively ended the U.S.

aid program in Afghanistan.(13)

Pakistan, meanwhile, looked with growing suspicion on the apparent

development of a Moscow-New Delhi-Kabul alliance.(14) For the next two

years, Afghanistan and Pakistan traded vitriolic radio and press

propaganda as Afghan-supported insurgents fought Pakistani units inside

the Northwest Frontier Province. On March 9, 1963, Daoud stepped down.

Two months later, with the mediation of the Shah of Iran, Pakistan and

Afghanistan reestablished diplomatic relations.

Nevertheless, the Pushtunistan issue did not disappear. In 1964,

Zahir Shah called a loya jirga — a general assembly of tribal leaders

and other notables — during which several delegates spoke out on the

issue. Subsequent Afghan prime ministers continued to pay lip service to

the issue, keeping the irritant in Afghan-Pakistani relations alive.

Even if Kabul’s support for Pushtun nationalist aspirations did not

pose a serious challenge to the integrity of Pakistan, the impact on

Pakistan-Afghanistan relations was lasting. As Barnett Rubin commented

in his 1992 study, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, “The resentments

and fears that the Pashtunistan issue aroused in the predominantly

Punjabi rulers of Pakistan, especially the military, continue to affect

Pakistani perceptions of interests in Afghanistan.”(15)

THE RETURN OF DAOUD AND THE RISE OF THE ISLAMISTS

In 1973, Daoud overthrew his cousin Zahir Shah and declared

Afghanistan a republic. Pakistan, still reeling from the secession of

Bangladesh, feared a return of the fierce Pushtun nationalism of Daoud’s

first term. Meanwhile, Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev, embracing a

strategy of Third World activism, sought to exploit Daoud’s coup to

retrench Soviet regional interests.(16)

In 1971, Pakistan fought a bloody and, ultimately unsuccessful, war

to prevent the secession of East Pakistan which, backed by India, had

declared its independence as Bangladesh. While Pakistan had been founded

on the basis of Islamic unity, the 1971 war reinforced the point that

in Pakistan, ethnicity trumped religion. Accordingly, Pakistan viewed

Daoud’s Pushtunistan rhetoric (and his simultaneous support for Baluchi

separatists), as well as his generally pro-India foreign policy, as a

serious threat to Pakistani security.

Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto responded by supporting

an Islamist movement in Afghanistan, a strategy that Islamabad would

replicate two decades later with the Taliban.(17) For Islamabad, the

strategy was two-fold. Not only could Pakistan deter Afghan expansionism

by pressuring Afghanistan from within, but also a religious opposition

would have broad appeal in an overwhelmingly Muslim country without the

implicit territorial threat of an ethnic-nationalist opposition. It was

from this Islamist movement that Pakistan’s intelligence agency,

Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), would introduce the United States to

such important later mujahidinfigures as Burhanuddin Rabbani, Ahmad Shah

Masud, and Gulbuddin Hikmatyar. The latter is actually a Ghilzai

Pushtun, but from the north, with only limited links to the Pushtuns of

the south. Accordingly, he was not considered a Pushtun nationalist by

his Pakistani benefactors (or most Afghans).(18)

In 1974, the Islamists plotted a military coup, but Daoud’s regime

discovered the plot and imprisoned the leaders — at least those who did

not escape to Pakistan. The following year, the Islamists attempted an

uprising in the Panjshir Valley. Again they failed, and again the

Islamist leaders fled into Pakistan. Islamabad found that supporting an

Afghan Islamist movement both gave Pakistan short-term leverage against

Daoud, and also a long-term card to play should Afghanistan again seek

to strategically challenge its neighbor to the East. With a sympathetic

force in Afghanistan, Pakistan would be better able to influence

succession should the elderly Daoud die. It was thus in the mid-1970s,

while both the United States and the Soviet Union continued to ply the

Kabul regime with aid, that Pakistani intelligence — with financial

support for Saudi Arabia — first began their ties to the Islamist

opposition in Afghanistan.(19)

THE SAUR REVOLUTION

Under Daoud’s presidency, Afghanistan became increasingly polarized.

The Islamists were by no means the only opposition seeking to reshape

the status quo. Just as Pakistan backed the Islamist opposition, the

Soviet Union threw its encouragement behind the People’s Democratic

Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), sometimes referred to by either of its two

constituent factions, the Khalq and the Parcham. The Khalq and the

Parcham effectively remained competitors under separate leadership

between 1967 and 1977, when the Soviet Union pressured them to reunite.

Why did the Soviet Union shift its support from Daoud, with whom it

previously had a good relationship? Barnett Rubin explains that Soviet

policy toward the Third World underwent a fundamental shift in the

1970s. The ouster of President Sukarno in Indonesia and Anwar Sadat’s

decision to expel Soviet advisers from Egypt convinced Moscow that it

could no longer rely on non-communist nationalists. Simultaneously, the

American defeat in Vietnam had emboldened the Soviet Union to push

harder and compromise less.(20)

In 1978, a leading Parcham official fell to an assassin’s bullet.

Massive demonstrations erupted against Daoud and the CIA, which Parcham

blamed for the killing. Daoud responded by arresting the PDPA

leadership, spurring military officers sympathetic to the PDPA to move

against his government. On April 27, 1978, they seized power in a bloody

coup. On April 30, a Revolutionary Council declared Afghanistan to be a

Democratic Republic.

The Soviet Union welcomed the new regime with a massive influx of

aid. However, the old rivalries between the Khalqis, who dominated the

new government, and the Parchamis, crippled the regime. Hafizullah Amin

sought to implement the Khalq’s program through brute force and terror,

alienating many of his former partners. The Soviet Union, witnessing the

disintegration of state control, sought to salvage their influence in

Afghanistan through a change of leadership, but Hafizullah Amin refused

to accept Soviet dictates.

THE SOVIET INVASION

Having lost in Iran’s Islamic revolution their staunchest regional

ally, the United States again sought to engage Afghanistan. In December

1979, Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev, not willing to lose the tenuous

Soviet advantage in Afghanistan, sent the Red Army pouring into the

country. When Hafizullah Amin still refused to relinquish power, Soviet

units stormed his palace and executed him. While the Red Army and its

client regime in Kabul controlled the city, the Soviets were never fully

able to gain control over the countryside. Pockets of resistance

continued despite all attempts to stamp them out.

Despite the oversimplifications of some in academe and opponents of

the military campaign against the Taliban, the mujahidin was not simply

created by the CIA in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion. Rather, as

Red Army crack soldiers flew on Aeroflot planes into Kabul, and as

Soviet tanks rolled across the Friendship Bridge from what is now

Uzbekistan, a cadre for the enlargement of the Afghan mujahidin already

existed. This cadre had remained in Pakistani exile since their failed

uprising four years before. However, even if the mujahidin existed prior

to the Soviet invasion, it was the occupation of a foreign power that

caused the mujahidin movement to grow exponentially in both influence

and size as disaffected Afghans flocked to what had become the only

viable opposition movement.

ARMING THE AFGHAN RESISTANCE

The decision to arm the Afghan resistance came within two weeks of

the Soviet invasion, and quickly gained momentum.(21) In 1980, the

Carter administration allocated only $30 million for the Afghan

resistance, though under the Reagan administration this amount grew

steadily. In 1985, Congress earmarked $250 million for Afghanistan,

while Saudi Arabia contributed an equal amount. Two years later, with

Saudi Arabia still reportedly matching contributions, annual American

aid to the mujahidin reportedly reached $630 million.(22) This does not

include contributions made by other Islamic countries, Israel, the

People’s Republic of China, and Europe. Many commentators cite the huge

flow of American aid to Afghanistan as if it occurred in a vacuum; it

did not. According to Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid, the Soviet

Union contributed approximately $5 billion per year into Afghanistan in

an effort to support their counterinsurgency efforts and prop up the

puppet government in Kabul.(23) Milton Bearden, Central Intelligence

Agency station chief in Pakistan between 1986 and 1989, commented that

by 1985, the occupying Soviet 40th army had swollen to almost 120,000

troops and with some other elements crossing into the Afghan theater on a

temporary duty basis.(24)

Initially, the CIA refused to provide American arms to the

resistance, seeking to maintain plausible deniability.(25) (The State

Department, too, also opposed providing American-made weapons for fear

of antagonizing the Soviet Union.(26) The 1983 suggestion of American

Ambassador to Pakistan Ronald Spiers, that the U.S. provide Stingers to

the mujahidin accordingly went nowhere for several years.(27) Much of

the resistance to the supply of Stinger missiles was generated

internally from the CIA station chief’s desire (prior to the accession

of Bearden to the post) to keep the covert assistance program small and

inconspicuous. Instead, the millions appropriated went to purchase

Chinese, Warsaw Pact, and Israeli weaponry. Only in March 1985, did

Reagan’s national security team formally decide to switch their strategy

from mere harassment of Soviet forces in Afghanistan to driving the Red

Army completely out of the country.(28) After vigorous internal debate,

Reagan’s military and national security advisors agreed to provide the

mujahidin with the Stinger anti-aircraft missile. At the time, the

United States possessed only limited numbers of the weapon. Some of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff also feared accountability problems and

proliferation of the technology to Third World countries.(29) It was not

until September 1986, that the Reagan administration decided to supply

Stinger anti-aircraft missiles to the mujahidin, thereby breaking the

embargo on “Made-in-America” arms.

[While there was significant fear of Stinger missiles falling into

the wrong hands in the 1990s, very little attention was paid to the

threat from the anti-aircraft missiles in the 2001 U.S. campaign against

the Taliban. This may have been due to an early 1990s covert campaign

to purchase or otherwise recover surplus Stinger missiles still in the

hands of the mujahidin factions .](30)

The CIA may have coordinated purchase of weapons and the initial

training, but Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) controlled

their distribution and their transport to the war zone. John McMahon,

deputy director of the CIA, attempted to limit CIA interaction with the

mujahidin. Even at the height of American involvement in Afghanistan,

very few CIA operatives were allowed into the field.(31) Upon the

weapons’ arrival at the port of Karachi or the Islamabad airport, the

ISI would transport the weapons to depots near Rawalpindi or Quetta, and

hence on to the Afghan border.(32)

The ISI used its coordinating position to promote Pakistani interests

as it saw them (within Pakistan, the ISI is often described as “a state

within a state”).(33) The ISI refused to recognize any Afghan

resistance group that was not religiously based. Neither the Pushtun

nationalist Afghan Millat party, nor members of the Afghan royal family

were able to operate legally in Pakistani territory. The ISI did

recognize seven groups, but insisted on contracting directly with each

individual group in order to maintain maximum leverage. Pakistani

intelligence was therefore able to reward compliant factions among the

fiercely competitive resistance figures.(34) Indeed, the ISI tended to

favor Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, perhaps the most militant Islamist of the

mujahidin commanders, largely because Hekmatyar was also a strong

proponent of the Pakistani-sponsored Islamist insurgency in Kashmir.(35)

Masud, the most effective Mujahid commander, but a Tajik, received only

eight Stingers from the ISI during the war.

Outside observers were not unaware that Pakistan had gained

disproportionate influence through aid distribution. However, India, the

greatest possible diplomatic check to Washington’s escalating

relationship with Islamabad, removed herself from any position of

influence because its unabashed pro-Soviet policy eviscerated any

American fear of antagonizing India. The U.S. State Department

considered India a lost cause.(36)

While beneficial to Pakistani national interests at least in the

short-term, the ISI’s strategy had long-term consequences in promoting

the Islamism and fractiousness of the mujahidin. However, the degree to

which disunity would plague the mujahidin did not become fully apparent

until after the withdrawal of the Soviet army from Afghanistan.

Afghanistan was a bleeding wound for the Soviet Union. Each year, the

Red Army suffered thousands of casualties. Numerous Soviets died of

disease and drug addiction. The quick occupation had bogged down into a

huge economic drain at a time of tightening Soviet resources. In 1988,

Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev announced his intention to withdraw

Soviet troops. Despite Gorbachev’s continued military and economic

assistance to Najibullah, Afghanistan’s communist president, most

analysts believed the Najibullah would quickly collapse. The CIA

expected that, at most, Najibullah would remain in power for one year

following the Soviet withdrawal.

However, Najibullah proved the skeptics wrong. Mujahidin offensives

in the wake of the Soviet withdrawal failed. Washington had only

budgeted money to support the mujahdin for one year following the Soviet

withdrawal, but Saudi and Kuwaiti donors provided emergency aid, much

of which went to Hikmaytar and other Wahabi commanders.(37) While the

United States budgeted $250 million for the mujahidin in 1991, the

following year the Bush administration allocated no money for military

assistance. Money is influence, and individuals in the Persian Gulf

continued to provide almost $400 million annually to the Afghan

mujahidin.(38)

Many Afghan specialists criticized the United States for merely

walking away from Afghanistan after the fall of the Soviet Union. Ed

Girardet, a journalist and Afghanistan expert, observed, “The United

States really blew it. They dropped Afghanistan like a hot potato.”(39)

Indeed, Washington’s lack of engagement created a policy void in which

radical elements in the ISI eagerly filled. However, to consider

Afghanistan in a vacuum ignores the crisis that developed when, on

August 2, 1990, Iraqi troops invaded Kuwait. Washington’s attention and

her resources shifted from the last battle of the Cold War to a

different type of conflict.

Islamist commanders like Hikmaytar, upset with the U.S.-led coalition

in the Persian Gulf, broke with their Saudi and Kuwait patrons and

found new backers in Iran, Libya, and Iraq. [Granted, while the break

was sudden, the relationship with Tehran was not. Hikmaytar had started

much earlier to collaborate with Iran]. It was only in this second phase

of the Afghan war, a phase that developed beyond much of the Western

world’s notice, that Afghan Arabs first became a significant political,

if not military, force in Afghanistan.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE AFGHAN ARABS

One of the greatest criticisms of U.S. policy, especially after the

rise of the Taliban, has been that the CIA directly supported Arab

volunteers who came to Afghanistan to wage jihad against the Soviets,

but eventually used those American arms to engage in terrorist war

against the West. However, the so-called “Afghan Arabs” only emerged as a

major force in the 1990s. During the resistance against the Soviet

occupation, Arab volunteers played at best a cursory role.

According to a former intelligence official active in Afghanistan

during the late 1980s, the Arab volunteers seldom took part in fighting

and often raised the ire of local Afghans who felt the volunteers merely

got in the way. In an unpublished essay, a military officer writing

under the name Barney Krispin, who worked for the CIA during its support

of the Afghan mujahidin’s fight against the Soviet Army, summoned up

the relationship between Afghan and non-Afghan fighters at that time:

The relationship between the Afghans and the Internationalists was

like a varsity team to the scrubs. The Afghans fought their own war and

outsiders of any stripe were kept on the sidelines. The bin Ladin’s of

this Jihad could build and guard roads, dig ditches, and prepare fixed

positions; however, this was an Afghan Jihad, fought by real Afghans,

and eventually won by real Afghans. Bin Ladin sat out the ‘big one.’

Milton Bearden, former CIA station chief in Pakistan, was equally blunt, writing:

Despite what has often been written, the CIA never recruited,

trained, or otherwise used the Arab volunteers who arrived in Pakistan.

The idea that the Afghans somehow needed fighters from outside their

culture was deeply flawed and ignored basic historical and cultural

facts.

Bearden continued to explain though that while the Afghan Arabs were

“generally viewed as nuisances by mujahidin commanders, some of whom

viewed them as only slightly less bothersome than the Soviets,” the work

of Arab fundraisers was appreciated.(40)

In 1995, Ali Ahmad Jalali, a former Afghan Army Colonel and top

military planner on the directing staff of the Islamic Unity of Afghan

Mujahidin, along with Lt. Col. Lester W. Grau, US Army, ret., a career

Soviet Foreign Area Officer, published a collection of essays by

mujahidin commanders explaining their tactics in various engagements.

Throughout their essays, various commanders make reference to the

presence of Afghan Arabs, often in ways which indicate their combat role

was marginal at best. For example, describing a 1987 mujahidin raid on a

division garrison in Kandahar, Commander Akhtarjhan commented, “We had

some Arabs who were with us for jihad credit. They had a video camera

and all they wanted to do was to take videos. They were of no value to

us.”(41) Similar comments were made by other commanders.

So where did the Afghan Arabs come from? Many of the volunteers

originated in the Muslim Brotherhood or other radical Islamist

organizations. The Saudi Arabia-based Islamic Coordination Council

organized both the new recruits, and disbursement of assistance. In

Pakistan, Arab volunteers staffed numerous Saudi Red Crescent offices

near the Afghan frontier.

The Arab volunteers also disproportionately gravitated to the

Ittihad-i Islami (Islamic Union), led by Abd al-Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf.

Sayyaf was a Pushtun, but he long lived in Saudi Arabia, had studied at

al-Azhar in Cairo, and spoke excellent Arabic. Sayyaf preached a strict

Salafi version of Islam critical of manifestations of both Sufism and

tribalism in Afghanistan. However, successful as he was with Saudi

financiers, he remained unpopular among ordinary Afghans both because of

his rampant corruption and also because Afghans considered both Sayyaf

and his fundamentalist brand of Islam foreign.(42)

Even without a central role in the jihad, though, Afghan Arabs did

establish a well-financed presence in Afghanistan (and the border

regions of Pakistan). While he does not cite his source, Pakistani

journalist Ahmed Rashid estimated that between 1982 and 1992, some

35,000 Islamists would serve in Afghanistan.(43)

Is the United States responsible for creating the Afghan Arab

phenomenon? It would be a gross over-simplification to ascribe the rise

of the Taliban to mere “blowback” from Washington’s support of radical

Islam as a Cold War tool. After all, while many mujahidin groups are

fiercely religious, few adhere to the combative radicalism of the Arab

mercenaries. Nor can one simply attribute the rise of Islamic

fundamentalism to U.S. involvement, for this ignores the very real fact

that a country preaching official atheism occupied Afghanistan.

Nevertheless, by delegating responsibility for arms distribution to the

ISI, the United States created an environment in which radical Islam

could flourish. And, with the coming of the Taliban, radical Islam did

just that.

THE RISE OF THE TALIBAN

The Taliban seemingly arose from thin air. Newspapers like The New

York Times only deemed the Taliban worthy of newsprint months after it

had become the dominant presence in southern Afghanistan.(44) The rise

of the Taliban was accompanied by heady optimism. Just as many Iranian

opponents of the Islamic Republic freely admit to having initially

supported Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a wide variety of Afghans from

various social classes and cities told me in March 2000 that they too

were initially willing to give the Taliban a chance, even though few

still supported the movement at the time of my travel through the

Islamic Emirate. Teachers, merchants, teachers, and gravediggers all

said that the Taliban promised two things: Security and an end to the

conflict between rival mujahidin groups that continued to wrack

Afghanistan through the 1990s and, indeed, until the ultimate victory of

the Northern Alliance with U.S. air support in December 2001.

Following the 1989 withdrawal of the Soviet military, Afghan

president Najibullah managed to maintain power for three years without

his patrons. In 1992, ethnic Tajik mujahidin forces captured Kabul and

unseated the communist president. However, Rabbani, Ahmad Shah Masud,

and ethnic Uzbek commander General Rashid Dostum could not control the

prize. Hikmatyar immediately contested the new government that, for the

first time in more than three centuries (except for a ten-month

interlude in 1929), had put Tajiks in a predominant position. Hikatyar’s

forces took up positions in the mountains surrounding Kabul preceded to

shell the city mercilessly. Meanwhile, Ismail Khan controlled Herat and

much of Western Afghanistan, while several Pushtun commanders held sway

over eastern Afghanistan.

Kandahar and southern Afghanistan was in a state of chaos, with

numerous warlords and other “barons” dividing not only the south, but

also Kandahar city itself into numerous fiefdoms. Human Rights Watch

labeled the situation in Kandahar “particularly precarious,” and noted

that, “civilians had little security from murder, rape, looting, or

extortion. Humanitarian agencies frequently found their offices stripped

of all equipment, their vehicles hijacked, and their staff

threatened.”(45) Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid argued that the

internecine fighting, especially in Kandahar, had virtually eliminated

the traditional leadership, leaving the door open to the Taliban.(46)

Afghanistan became a maelstrom of shifting alliances. Dostum defected

from his alliance with Rabbani and Masud, and joined Himatyar in

shelling the capital. The southern Pushtun warlords and bandits

continued to fight each other for territory, while continuing to sell

off Afghanistan’s machinery, property, and even entire factories to

Pakistani traders. Kidnappings, murders, rapes, and robberies were

frequent as Afghan civilians found themselves in the crossfire.

It was in the backdrop to this fighting that the Taliban arose, not

only in Afghanistan, but also among Afghan refugees and former mujahidin

studying in the madaris (religious colleges) of Pakistan. Ahmed Rashid

conducted interviews with many of the founders of the movement in which

they openly discussed their distress at the chaos afflicting

Afghanistan. After much discussion, they created their movement based on

a platform of restoration of peace, disarmament of the population,

strict enforcement of the shari’a, and defense of the “Islamic

character” of Afghanistan.(47) Mullah Muhammad Umar, an Afghan Pushtun

of the Ghilzai clan and Hotak tribe who had been wounded toward the end

of the conflict with the Soviet army, became the movement’s leader.

The beginning of the Taliban’s activity in Afghanistan is shrouded in

myth. Ahmed Rashid recounted what he deemed the most credible:

Neighbors of two girls kidnapped and raped by Kandahar warlords asked

the Taliban’s help in freeing the teenagers. The Taliban attacked a

military camp, freed the girls, and executed the commander. Later,

another squad of Taliban freed a young boy over whom two warlords were

fighting for the right to sodomize. A Robin Hood myth grew up around

Mullah Umar resulting in victimized Afghans increasingly appealing to

the Taliban for help against local oppressors.(48)

Territorial conquest began on October 12, 1994, when 200 Taliban

seized the Afghan border post of Spin Baldak. Less than a month later,

on November 3, the Taliban attacked Kandahar, the second-largest city in

Afghanistan. Within 48 hours, the city was theirs. Each conquest

brought the Taliban new equipment and munitions — from rifles and

bullets to tanks and MiG fighters, for their continued advance.(49) The

Taliban maintained their momentum and quickly seized large swathes of

Afghanistan. By February 11, 1995, they controlled 9 of Afghanistan’s 30

provinces. On September 5, 1995, the Taliban seized Herat, sending

Ismail Khan into an Iranian exile. Just over one year later, Jalalabad

fell, and just 15 days later, on September 26, 1996, the Taliban took

Kabul.

A stalemate ensued for almost eight months, but shattered when

General Malik rebelled against Dostum, allowing Taliban forces into the

north. On May 24, 1997, the Taliban seized Mazar-i Sharif, the last

major city held by the mujahidin. However, after just 18 hours, a

rebellion forced the Taliban from the city. When the Taliban again took

the refugee-swollen city in August 1998, they took no chances, brutally

massacring thousands. With Dostum in an Uzbek exile, the only major

mujahidin commander remaining was Ahmad Shah Masud, nicknamed ‘the Lion

of the Panjshir’ for his heroism during the war against the Soviets.(50)

While supported materially by Pakistan, the Taliban relied heavily

upon momentum in its near-complete conquest of Afghanistan. Following

the fall of Kandahar, thousands of Afghan refugees, madrasa students,

and Pakistani Jamiat-i Ulama supporters rushed to join the movement.

Ahmed Rashid estimates that by December 1994, more than 12,000 recruits

joined the Taliban.(51) Each subsequent Taliban victory resulted in

thousands of new recruits. Often these victories were less a result of

military prowess than cooption of opposing warlords into the Taliban

movement.

I was in Mazar-i Sharif in 1997, when the Taliban first marched on

the city. Their advance was surprisingly fast (leaving foreigners in the

city scrambling to evacuate). The reason was they had simply coopted

General Dostum’s deputy Malik, who was in command of the neighboring

province. Rather than fighting their way through more than 100

kilometers, the Taliban force suddenly found themselves with free

passage to within a dozen kilometers of the city.

Stalemate ensued as the Taliban were unable to gain significant

ground against Masud, who retained control of between 5 and 10 percent

of Afghan territory. The fight between the mujahidin forces commanded by

Masud and the Taliban became a fight between those who had been

beneficiaries of American assistance in the 1980s, and those who had

sprung to prominence in the aftermath of American withdrawal from Afghan

affairs.

PAKISTANI SUPPORT FOR THE TALIBAN

The Taliban became the latest incarnation of Pakistan’s desire to

support Islamist rather than nationalist rule in neighboring

Afghanistan. The Taliban arose in madaris on Pakistani territory. Upon

the capture of Spin Baldak, mujahidin commanders in Kandahar immediately

accused Pakistan of supporting the new group. In late October 1994, the

local mujahidin warlords intercepted a convoy containing arms, senior

ISI commanders, and Taliban.(52) The men and material in this transport

proved crucial in the seizure of Kandahar.

Even after the stalemate ensued between the Taliban and Ahmad Shah

Masud, Pakistan provided the Taliban with a constant flow of new

recruits. Rumors spread throughout the city while I was there that 5,000

new ‘Punjabis’ were on their way into Afghanistan to supplement the

fight against Masud. Former Defense Intelligence Agency analyst Julie

Sirrs gained access to Taliban prisoners held by Ahmed Shah Masud; among

them were several Pakistani mercenaries.

Merchants in the book market in central Kabul talked about seeing

many Pakistanis “here for jihad.” In Rish Khor, on the outskirts of

Kabul, operated a training camp for the Harakat ul-Mujahidin, a

Pakistani-supported terrorist group waging a separatist campaign against

India.(53) It was members of this group that hijacked an Air India

flight from Nepal to Kandahar in December 1999, eventually releasing the

hostages after Taliban mediation and escaping. Afghanistan provided a

useful base not only to train pro-Pakistani militants and terrorists,

but also to give them field experience.

While politicians in Islamabad repeatedly denied that Pakistan

supported the Taliban, the reality was quite the opposite.(54) While

some Taliban trade occurred with Turkmenistan and even Iran, and the

Taliban benefited from the supply of opium to all of its neighbors,

Pakistan remained the effective diplomatic and economic lifeline for the

Taliban’s Islamic Emirate. Senior ISI veterans like Colonel “Imam”

Sultan Amir functioned as district advisors to the regional Taliban

leadership. Pakistan also supplied a constant flow of munitions and

recruits for the Taliban’s war with the Northern Alliance, and provided

crucial technical infrastructure support to allow the Taliban state to

function.(55)

This did not represent a radical change in Pakistan’s Afghanistan

policy. Rather, Islamabad’s support of the Taliban was simply a

continuation of a pattern to support Islamist rather than nationalist

factions inside its neighbor. Nor was the ISI the only supporter of the

Taliban within the Pakistan government. Former Prime Minister Benazir

Bhutto’s interior minister Nasrullah Babar also staunchly supported the

group. Robert Kaplan, correspondent for The Atlantic Monthly went so far

as to argue that Bhutto and Babar “conceived of the Taliban as the

solution to Pakistan’s problems.”(56) Ahmed Rashid commented, “The

Taliban were not beholden to any single Pakistani lobby such as the ISI.

In contrast the Taliban had access to more influential lobbies and

groups in Pakistan than most Pakistanis.”(57)

Taliban volunteers, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, described

Pakistani instructors at Rish Khor which, according to Afghans I

interviewed, also served as a training camp for the Harakat

ul-Mujahidin, the violent Kashmiri separatist group engaged in terrorist

operations against India.(58) Citizens of Kabul derisively spoke of

“Punjabis,” volunteers from Pakistan. Guarding ministries in Kabul in

March 2000 were Taliban officials who only spoke Urdu, and did not speak

any Afghan language. The Pakistani government did not dispute reports

that thousands of trained Pakistani volunteers serving with the

Taliban.(59)

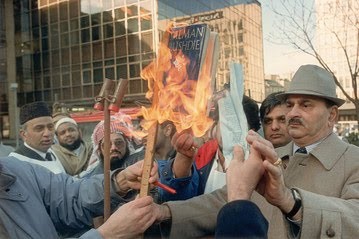

While the Pakistani government was directly complicit in some forms

of support for the Taliban, just as important was its indirect support.

In 1971, there were only 900 madaris (religious seminaries) in Pakistan,

but by the end of President Zia ul Haq’s administration in 1988, there

were over 8,000 official madaris, and more than 25,000 unregistered

religious schools.(60) By January 2000, these religious seminaries were

educating at least one-half million children according to Pakistan’s own

estimates.(61) The most prominent of the seminaries — the Dar al-Ulum

Haqqania from which the Taliban leadership was disproportionately drawn

— reportedly had 15,000 applications for only 400 spots in 1999.(62)

Ahmed Rashid comments that the mullahs running most of the religious

schools were but semi-literate themselves, and blindly preached the

religious philosophy adopted by the Taliban. Visiting one such religious

seminary in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks, students

told a Western reporter that, “We are happy many kaffirs [infidels] were

killed in the World Trade Center.” Regarding Muslim casualties in the

World Trade Center, one student responded, “If they were faithful to

Islam, they will be martyred and go to paradise. If they were not good

Muslims, they will go to hell.” The seminary students generally learn

only Islam, tainted with strong strain of anti-Westernism and

anti-Semitism.(63)

TALIBAN SUPPORT USAMA BIN LADIN

Where does Usama bin Ladin fit into the picture? The Taliban and

Usama bin Ladin’s al-Qa’ida network retained distinct identities.

Indeed, only in 1996 did Usama bin Ladin relocate from refuge with the

Sudanese government to the Taliban’s Afghanistan. Bin Ladin caused a

seeming paradox for Afghanistan watchers. On one hand, the Taliban,

recognized as the government of Afghanistan by only Pakistan, Saudi

Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, sought to break its isolation. On

the other hand, the Taliban continued to shelter Usama bin Ladin, even

after his involvement in the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in

Kenya and Tanzania.

As the media turned its attention to Afghanistan after September 11,

many commentators sought answers as to why the Taliban continued to host

Usama bin Ladin, despite the international ire that he brought to the

regime. CNN’s correspondent even went so far as to postulate that the

Taliban could not turn over Usama bin Ladin because of Afghanistan’s

tradition of hospitality (something which did not stop the Afghans from

killing nearly 17,000 British men, women, and children evacuating Kabul

under a truce during the First Afghan War in 1842.)

The answer to the paradox is actually much more mundane, and also a

result of the discrepancy in the fighting ability of the Taliban versus

the mujahidin commanders like Ahmad Shah Masud who had received U.S.

support and training in the 1980s. Masud remained undefeated against the

Red Army and, lacking both men and material, he managed to stubbornly

hold back the Taliban from the last five percent of Afghanistan not

under their control. Masud’s secret was superior training and a fiercely

loyal cadre of fighters. While the Taliban’s rank-and-file may have

talked jihad, more often than not they would flee or hide when the

bullets began to fly. Unlike Masud’s men, the Taliban simply were

incapable of fighting at night.

Bin Ladin brought with him to Afghanistan a well-equipped and

fiercely loyal division of fighters-perhaps numbering only 2,000. While

many of these trained in al-Qa’ida’s camps for terrorism abroad or

protected bin Ladin and his associates at their various safe-houses, bin

Ladin made available several hundred for duty on the Taliban’s

frontline with Masud, where they assured the Taliban of at a minimum

continued balance and stalemate. While the Taliban suffered a high

international cost for hosting bin Ladin, this was offset by the

domestic benefits the regime gained. The war with the Northern

Alliance-not recognition by Washington or even the Islamic World-was the

Taliban’s chief priority.

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE?

In hindsight, and especially after the World Trade Center and

Pentagon attacks, it is easy to criticize Washington’s shortsightedness.

But American policymakers had a very stark choice in the 1980s: Either

the United States could support an Afghan opposition, or they could

simply cede Afghanistan to Soviet domination, an option that might

result in an extension of Soviet influence into Pakistan.

Contrary to the beliefs of many critics of American foreign policy,

the United States is not able to dictate its desires even to foreign

clients. Washington needed Pakistan’s cooperation, but Pakistan was very

mindful of its own interests. Chief among these, especially following

the secession of Bangladesh in 1971, was minimizing the nationalist

threat to Pakistani integrity. Islamabad considered Afghanistan,

especially with successive Afghan government’s Pushtunistan claims, to

pose a direct challenge to Pakistani national security. Accordingly,

Islamabad only allowed religiously based rather than nationalist

opposition groups to operate on Pakistani territory. If American

policymakers wanted to oppose Soviet imperialism in Afghanistan, then

they simply would have to accede to Pakistani interests.

The United States is not without fault, however. Following the Soviet

Union’s collapse, Washington could have more effectively pressured

Pakistan to tone down the support for Islamic fundamentalism, especially

after the rise of the Taliban. Instead, Washington ceded her

responsibility and gave Pakistan a sphere of influence in Afghanistan

unlimited by any other foreign pressure.

NOTES

1. Robert Fisk, “Think-Tank Wrap-Up,” United Press International,

September 15, 2001; “Public Enemy No. 1, a title he always wanted,” The

Independent, August 22, 1998.

2. Mort Rosenblum, “Bin Ladin once

thought of as ‘freedom fighter’ for United States.” Chattanooga

Times/Chattanooga Free Press, September 20, 2001. Even some foreign

dignitaries have sought to promote the myth. In a December 7, 2001,

interview with the pro-Syrian Lebanese daily al-Safir, Egyptian

President Hosni Mubarak commented, “…When the so-called Mujahideen

went to Afghanistan, they became more extreme, and began to disseminate

extremist ideas. People like Omar Abd Al-Rahman and bin Laden were

American heroes.”

3. “Afghanistan,” The World Factbook 2001

(Washington: Central Intelligence Agency, 2001)

http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/index.html . (After more

than two decades of war, any statistics regarding Afghan demographics

must be considered only approximations.)

4. Ibid.

5. Vartan

Gregorian, “The Emergence of Modern Afghanistan: Politics of Reform and

Modernization, 1880-1946,” (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1969),

pp.29-32.

6. Louis Dupree, Afghanistan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980,) p.477.

7. Dupree, p.507.

8. Dupree, pp.510-511.

9. Dupree, pp.485-494.

10.

Barnett Rubin, Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and

Collapse in the International System (New Haven: Yale University Press,

1995,) p.82.

11. Dupree, pp.538-539.

12. Dupree, p.546.

13. “George Washington Ayub,” The New Republic, October 30, 1961, p.7.

14.

Amin Saikal, “The Regional Politics of the Afghan Crisis,” in: Amin

Saikal and William Maley, eds., The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989,)p.54.

15. Barnett Rubin, pp.63-64.

16.

T.H. Rigby, “The Afghan Conflict and Soviet Domestic Politics,” in:

Amin Saikal and William Maley, eds. The Soviet Withdrawal from

Afghanistan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989,) p.72.

17. Barnett Rubin, p.100.

18. Najmuddin A. Shaikh, “A New Afghan Government: Pakistan’s Interest,” Jang, (Internet edition)December 1, 2001.

19. Barnett Rubin, pp.100-101.

20. Barnett Rubin, p.99.

21.

Alan J. Kuperman, “The Stinger missile and U.S. intervention in

Afghanistan,” Political Science Quarterly, No. 2, Vol. 114, June 1999.

22. Barnett Rubin, pp.180-181.

23.

Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Islam, Oil, and the New Great Ga e in Central

Asia. (London and New York: I.B. Tauris and Company, 2000,) p.18.

24. Milton Bearden, “Afghanistan, Graveyard of Empires,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2001.

25. Ibid.

26. George Schulz, Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993,) p.692.

27. Kuperman, “The Stinger missile and U.S. intervention in Afghanistan”

28.

Steve Coll. “Anatomy of a Victory: CIA’s Covert Afghan War; $2 Billion

Program Reversed Tide for Rebels,” The Washington Post, July 19, 1992,

p.A1.

29. Kuperman, “The Stinger missile and U.S. intervention in Afghanistan”

30. Interview with former CIA operative, November 1998.

31. Kuperman, “The Stinger missile and U.S. intervention in Afghanistan,”

32. Barnett Rubin, p.197.

33. Pamela Constable, “Pakistani Agency Seeks to Allay U.S. on Terrorism,” The Washington Post, February 15, 2000, p.A17.

34. Barnett Rubin, pp.181,198-199.

35. Kuperman, “The Stinger missile and U.S. intervention in Afghanistan”

36. Amin Saikal. “The Regional Politics of the Afghan Crisis,” p.59.

37. Barnett Rubin, p.182.

38. Barnett Rubin, p.183.

39.

Mort Rosenblum, “bin Ladin once thought of as ‘freedom fighter’ for

United States,” Chattanooga Times/Chattanooga Free Press, September 20,

2001.

40. Bearden, “Afghanistan, Graveyard of Empires,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2001.

41.

Commander Akhtarjhan, “Raid on 15 Division Garrison,” In: Ali Ahmad

Jalali and Lester W. Grau, eds. The Other Side of the Mountain:

Mujahideen Tactics in the Soviet-Afghan War. (Quantico, Virginia: The

United States Marine Corps Studies and Analysis Division, 1995,)p.396.

42. Rubin, 223-224; Rashid, p.85.

43. Rashid, p.130.

44. See: John Burns. “New Afghan Force Takes Hold, Turning to Peace,” The New York Times, February 16, 1995, p.A3.

45. “Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, July, 2001, Vol. 13, No. 3, p.15.

46. Rashid, p.19.

47. Rashid, p.22.

48. Rashid, p.25-26.

49. “Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, July, 2001, Vol.13, No. 3, p.15.

50. See chronology in Rashid, p.226-235.

51. Rashid, p.29.

52. Rashid, p.28.

53.

Michael Rubin and Daniel Benjamin, “The Taliban and Terrorism: Report

from Afghanistan,” Policywatch, The Washington Institute for Near East

Policy, No. 450, April 6, 2000.

54. For Pakistani denials of support

for the Taliban, see: Pamela Constable. “Pakistani Agency Seeks to Allay

U.S. on Terrorism,” The Washington Post, February 15, 2000, p.A17.

55. “Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, July, 2001, Vol.13, No. 3, p.23.

56.

Robert Kaplan, “The Lawless Frontier; tribal relations, radical

political movements and social conflicts in Afghanistan-Pakistan

border,” The Atlantic Monthly, September 1, 2000.

57. Amit Baruah. “Pak. Ripe for Taliban-style revolution,” The Hindu, February 24, 2000.

58. “Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, July, 2001, Vol. 13, No. 3, p.29.

59. Gregory Copley, “Pakistan Under Musharraf,” Defense and Foreign Affairs’ Strategic Policy, January 2000.

60. Rashid, p.89.

61. Gregory Copley, “Pakistan Under Musharraf,” Defense and Foreign Affairs’ Strategic Policy, January, 2000.

62.

Reuel Marc Gerecht, “Pakistan’s Taliban Problem; And America’s Pakistan

Problem,” The Weekly Standard, Vol. 7, No. 8, 2001, p.24.

63. Barry

Shlachter, “Inside Islamic seminaries, where the Taliban was born,” The

Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 2001. The views of the Pakistani

madrasa students were equally anti-Western before the September 11

attacks. See: Robert Kaplan, “The Lawless Frontier; tribal relations,

radical political movements and social conflicts in Afghanistan-Pakistan

border,” The Atlantic Monthly, September 1, 2000.

….

Link (1): commentarymagazine.com/will-afghanistan-turn-the-tables-on-pakistan/

Link (2): michaelrubin.org/1220/who-is-responsible-for-the-taliban

….

regards