…how bad things are between Washington and Delhi…this reluctant partnership might be best left to wither…scant evidence of being the man who will

shake up the economy……scuttling of a WTO deal…..calls into question……ardor for free trade……

……

This is a strange truth that no fiction can beat.

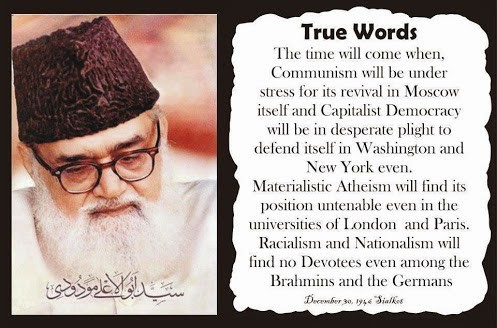

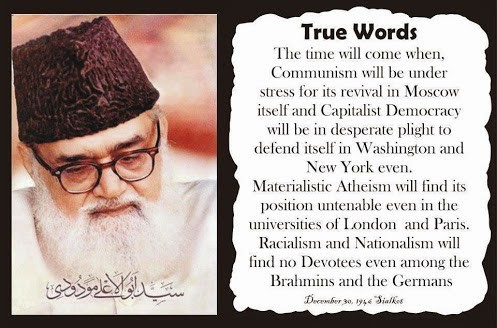

The person who correctly visualized the future amidst the hellish fog that was Partition(I) was an Islamist philosopher-king named Abul Ala Maududi.

…….

….

A lot of truth and wisdom in the above quotation…except for one thing. What would the future hold for Islam and muslims (especially those in South Asia), which in those glorious post-partition days held the promise to sweep out capitalism, communism, “materialistic atheism,” racialism and nationalism?

An honest analysis would point out that Maududi had the right instincts (partition will divide and weaken muslims) but the wrong principles (unite muslims by killing other muslims).

……..

Maududi was born in 1903 in Aurangabad, a city named after Aurangzeb, who was famous for his not-so-soft heart towards the majority of his citizens. Indeed, when the two nation theory talks eloquently about their villains being our heroes, Aurangzeb is Exhibit (A).

Hindus (left-liberals) hate the Last of the Great Badshahs and would like to believe that his actions destroyed the “secular” Mughal Empire. Hindus (conservatives) hate him and would like to dial back the clock to the Arab invasion of Sindh.

Muslims OTOH venerate Sultan Alamgir for having (violently) corrected the apostasies of his ancestors. They would like to believe that the green flag was planted across al-Hind for good, only to be undone by the treachery of a single (bengali) muslim: Mir Jafar.

Maududi opposed the formation of Pakistan because he instinctively understood that the power base for muslims in South Asia would be divided. However he was an exception. Muslims were a minority and out of power for 200 years, but they sincerely believed (and so did everybody else) in the one Muslim = 10 Hindus equation (Sikhs were a different story).

…….

The magic lines floated in the air: “Sylhet nilam vote-er jorey, Cachar nebo lathir jorey” – we muslims have won Sylhet district (Bangladesh), through elections and we will win Cachar district (Asom) using force. When the partition was formalized the confident leaders of Pakistan reassured the troops noting that muslims will be kings in Pakistan and king-makers in India. The confidence that comes from a hard battle won through a mix of votes and force seemed to settle all doubts.

Still Maududi worried about the division. One possible reason: his beloved home-land, Hyderabad (a princely state ruled by the Nizam) was unlikely to be a part of Pakistan and would be surrounded by the enemy on all sides. He may have worried about the unreliability of “impure” bengalis, of the possibility of millions of Mirjafars. He certainly worried about the un-islamic character (as he saw it) of the man leading the charge for partition.

Nevertheless Maududi had a change of heart and was confident enough to launch the first muslim-on-muslim riots in Pakistan in 1953. He was sentenced to death for his role in killing Ahmadis but the order was reversed. When this happened, the fate of Pakistan as a homeland for all muslims in South Asia was doomed.

If Muslims were out of power for 200 years, Hindus were under the colonial boot for a 1000 years. Plus there was the primacy of caste, there was really never one Hindu nation, just a thousand squabbling tribes. The only way to unite them was through careful inculcation of hate against muslims (not a difficult job, muslims helped out as well) and to create a fear factor around mad, bad Pakistan (not a difficult job, Pakistan helped out as well).

And so it is that finally in 2014, the nightmare that Maududi had envisioned, finally came into existence. The second republic is now born, there will be no muslim armies marching to take over the Red Fort.

………………………………………

These are early days but there are a few emerging clues as to the how the born-again nation will react (and reach out) to the world. Indeed the alarm bells have started ringing in unexpected places, while sworn enemies have remained quiet. What to make of all this?

What is quite clear is that the Hindu Desh wants to be friends with the family (Nepal, Bhutan, and…Sri Lanka…very tricky that one). They would even not mind breaking bread with the enemy (the Islamic nations in South Asia). We are talking of sincere, we do not want to be big brother, courteous hand of friendship, not the contemptuous, we are way bigger than you aloof attitude of the Congress wallahs. How can this be possible?

Well it is certainly not an unprecedented thing to have happened. Indo-Pak relations for example, have been generally more cordial when (on rare occasions) the Hindu Brotherhood has been at the high table. Thus Atal Bihari Vajpayee is rated highly by Pakistanis. The fire-breathing LK Advani went on a praise Jinnah tour, while Jaswat Singh came out with a Nehru villain book. Due to the curious nature of the politics of the sub-continent, Nehru the secularist is a villain for both conservative Hindus and Muslims – TNT version 2.0!!! The last screw in the coffin will be turned when Gujaratis of today will bow before Sardar Patel and say bye to Gandhi.

The consequence(s) of all this will be clear in due time, but some fictions have become facts on the ground. India is now officially declared to be a Hindu-first and Hindi-first nation. The only feeble resistance to this will come from Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Bengal (which form part of the un-India in this model) and the Kashmir valley and a few North-Eastern states. Asom, Punjab and Telengana- deeply disturbed spots all at some time or other- are now very much part of the national narrative.

…………………………

India already has open borders with Nepal and Bhutan, what is a (still remote) possibility now is an open border with Bangladesh. Only Modi can achieve this miracle. It is already the case that 10 million Bangla migrants are settled in India, and cattle-beef and food stuff goes the other way. The Hindus will at some point of time completely migrate out of Bangla, this will in turn help reduce tensions. Now the only people who will get killed are bengali muslims….in India (by Hindus, Sikhs, Tribals,…) and in Bangla (by other muslims).

The road to peace with Pakistan goes through Kashmir. The indications are that the original package will be revived: self-rule (but not independence) and a new twist: Union Territory for Pandits. Pakistan may agree to this, even if Kashmiris see a future Israel-Palestine play (they would be correct). But given the realities, Kashmiris may have no choice but to obey. A deciding factor will be China, it is doubtful that Pakistan Army will not raise objections if Beijing advises to the contrary. China is seriously bothered by the insurgencies in Xinjiang and will like to shut down all islamist adventures in the neighborhood.

…………………………………….

What about the USA and the West? Well….they are the last in the queue and they are very upset indeed. Modi will drive a hard bargain in the political sphere. He is a serious student of history and will not be caught sleeping while the opposition gets to champion the cause of the “little farmer.” He will use the carrot of defense sector privatization (49% FDI) and the opening of the insurance market (if he can get the Congress to go along in the Rajya Sabha). Before any Indian markets are opened, he will insist on a generous visa regime from USA and Europe. That may be a non-starter due to domestic complusions in those countries (excepting Germany).

The expectation is that among the big powers Germany, China, France, Russia and Japan will be the new close friends….just because they can give India what she wants…energy, technology, and soft loans.

It is unclear what is that special trick that will click it for India-USA (and India-UK). American technology is considered high cost and Americans do not like to share (unlike Russia and France). More H1-Bs may be the answer, but it is easier perhaps to persuade Google and IBM to move more of their operations to India (shocking if true: one third of Apple techies are Indian).

…………………….

…..Should We Just Forget

About India?

Here’s how bad things are between

Washington and New Delhi these days: It’s news that Kerry even made the trip.

Why this reluctant partnership might be best left to wither.

So low is the bar in U.S.-India

relations right now that the best thing that can be said about John Kerry’s

two-day hop-over to New Delhi was that he went there at all. A relationship

that burst into true blossom under George W. Bush, one that held for many

Americans the promise of a mold-breaking alliance for the 21st century, lies

shabbily dormant. Indeed, the only memorable episode in Kerry’s visit was his

scolding by India’s foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj, for the NSA’s spying on

her political party.

….

Should America care? India has little or nothing to contribute to American

efforts to tackle the crises in Gaza, Ukraine, Syria, and Iraq. It is a reluctant

partner, at best, in Washington’s efforts to rein in Iran and will have no

truck with the West in any showdown with Vladimir Putin and Russia. Its incessant push for permanent membership of the United

Nations Security Council, while understandable for a country that is the

world’s second-most populous, isn’t exactly in America’s interests: New Delhi

and Washington frequently find themselves on different sides of votes on U.N.

resolutions.

….

The two countries converge in their legitimate fears of Chinese aggression

and expansion in Asia, but even here, India has been loath to embrace any

formal alliance that would act as a check on Beijing, for fear of provoking the

Chinese into military incursions into Indian territory that New Delhi is

shamefully unprepared to counter. Besides, in recent weeks, India has been

party to the setting up of a BRICS Bank, with Brazil, Russia, China, and South

Africa.

….

This institution was conceived as a way to break America’s global

financial hegemony—a word beloved in bureaucratic Delhi, where America is still

regarded with a suspicion that is as potent as it is irrational.

….

The BRICS Bank

looks, for all its founding rhetoric, like a platform for Chinese hegemony

instead. Once more, China appears to have taken India for a ride. But that is

another story.

….

India offers America nothing of concrete strategic value that Washington

cannot, currently, live without. Not only does it balk at an alliance of any

kind, its political and intellectual elites are wedded still to nonalignment,

that antediluvian credo from the years of the Cold War.

…..

Intellectual worthies

in New Delhi have cooked up something called “Non-alignment 2.0,” by which

“India must remain true to its aspiration of creating a new and alternative

universality.” For those masochists who want to acquaint themselves better with

this Cold War mummy come to life, I suggest a visit to this website. It will swiftly become clear

that there is no room in this starry-eyed arrangement for a compact with

Washington.

….

Forget matters strategic, you may say; banish from your head all thoughts of

a military or security handshake. What about economics? Doesn’t India matter to

America as a market, a place for wise and profitable investment? Here again,

Americans must resign themselves, for the moment, to disappointment.

….

For all Narendra Modi’s free-market rhetoric in the run-up to the

elections, for all the assurances given to investors in back rooms, he has

offered scant evidence, in his two months in power, of being the man who will

shake up the Indian economy and make his country a more rational place in which

to do business. His national budget was only marginally less squishy and Fabian

than other, recent Indian budgets, and Thursday’s capricious scuttling by India

of a World Trade Organization deal that would have vastly streamlined the global

trade system calls into question Modi’s professed ardor for free trade.

…..

American private enterprise has always tread cautiously in India, and there

is every indication that it will have to continue to tiptoe its way through,

around, and over the cactus grove of Indian regulations.

…..

The job of the Obama

administration (and that of a likely Hillary administration) will be to

persuade India to change its ways. That will be immensely difficult if Mr. Modi

continues to backtrack on economic reform. (Why is he doing so? Is it his

belief that, having won an emphatic but contentious election, he needs to

“buy” social harmony by embracing the sops and subsidies he inherited from the

previous quasi-socialist government of Manmohan Singh?)

….

So, as things stand, America gets neither strategic comfort nor a fair

economic opportunity from India. Perhaps it’s time for Washington to shrug its

shoulders and move on, leaving a warmer relationship with India to a time when

Indians have made up their muddled minds about the kind of country theirs is—or

ought to be.

……

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s two-day visit to Nepal, which

commenced yesterday, highlights yet again his government’s focus on

India’s immediate neighbourhood. Having made Bhutan his maiden foreign

port of call after assuming office, Modi is the first Indian PM to

undertake a bilateral Nepal visit since I K Gujral in 1997.

….

Despite deep cultural bonds, over the years suspicion and distrust have

come to tarnish the bilateral relationship. Modi would do well to

address the criticism that New Delhi’s engagement with Kathmandu has

been marked by inequality and interference.

….

Generosity ought to be the pillar of India’s

outreach to Nepal and other Saarc neighbours. This would help dispel the

perception among the latter that New Delhi harbours a big-brotherly

attitude when it comes to dealing them. A vibrant Saarc combined with

the gains made at the recent Brics summit will hold India in good stead

in an increasingly multi-polar world defined by dynamic geopolitics.

….

Having said that, it would be imprudent for New Delhi to focus solely

on relations with its neighbours or other emerging economies at the

cost of ties with the West. India needs technology and investments from

the EU and US to kick-start its economy and tackle unemployment.

Moreover, terrorism is an international scourge New Delhi can’t tackle

alone. Hence, it simply can’t burn bridges with the West.

……

In this

regard, the collapse of WTO discussions last week hurts India’s

reputation. India has been identified as the country that undermined a

settled deal — which it had committed to support last December in Bali.

………

A perception that India is an unreliable partner can make potential

western allies hesitant to commit political and financial capital to

nurture a strategic relationship. This is the last thing Modi needs as

he attempts to revamp India-US ties at his meeting with President Obama

later this year. New Delhi must strive for a golden mean and maintain a

balance between its relationship with the West and greater South-South

cooperation. This will raise India’s profile at the international high

table.

……………………………….

Each

time an election verdict is analysed, it is easy and convenient to

describe it as a new beginning. This is always true because any process

of winning and losing, of choosing and rejecting, inevitably involves

fresh starts.

Some elections also indicate a closure. While the Lok Sabha election

of 2014 is certainly a beginning — though exactly what it has begun is

something we will really and realistically figure out only in the coming

years — we do know what it has ended. It has brought to a close a

20-year cycle of politics that has dominated one-and-a-half generations

of Indians.

In the early 1990s, three social trends came to capture political

imagination in India. There was the BJP’s ascent on the back of

Hindutva, of Hindu anger, prejudice and assertion.

There was the Mandal project that symbolised the political

empowerment of the OBCs, particularly in north India, a phenomenon later

extended to Dalit pride by Mayawati and the BSP. Finally, there was

liberalisation and economic reform, the explosion of expectations and

the politics of growth. Mandir, Mandal and Market: So often in the

1990s, political assessments in India resorted to that lazy phrase.

Narendra Modi’s dramatic rise to power in 2014 and the impressive

mandate he has won have made that three-way split and that careful

separating of one motivation from another completely redundant. He is a

Hindu leader and mascot. He is an OBC from a traditionally

underprivileged caste background.

He is also the most passionate advocate of market-based

solutions, of enterprise and of the energies of the citizen — as opposed

to the eviscerating qualities of statism — that mass politics in India

has seen in a long, long time.

There is no point arguing whether Modi would be Right-wing or

capitalist in a western economic context, and whether he agrees with

every semicolon of Milton Friedman and every paragraph of Margaret

Thatcher. He doesn’t; but he shares their essential instincts and buys

into their broader logic much more than any other mainstream and

electable political leader in India today.

While Modi has made those abstruse debates about an ideological

battle between three (or more) ideas of India seem silly if not

irrelevant, what has he actually introduced and brought to the table?

The principal appeal of Modi in contemporary India is not religion or

caste or even hyper-nationalism.

It is class. The narrative of a self-made man, of the son of a

father who sold tea at a railway station and a mother who went house to

house washing dishes to pay school fees for her children, is a

compelling and extraordinarily powerful one.

The Congress leadership and the media completely missed how the

Modi narrative was resonating with the people. Mani Shankar Aiyar’s

puerile comment that the Congress would open a tea stall for Modi came

to showcase his party’s — and his peer group’s — complete alienation

from a certain popular urge and aspiration.

Aiyar saw it as a clever-clever line; the message it sent was one

of an unfeeling elite, happy to mock lesser citizens. It made being a

chaiwallah a badge of honour for Modi.

It established him as the underdog — a role he plays best, and

has played in successive elections in Gujarat, even while being chief

minister.

If this election was about Modi capitalising on a class revolt,

that expression has to be understood. The reference here is not to class

in a Marxian sense.

It is simply to primarily young, small town, semi-urban people —

or even rural folk, exposed to or associated with city life and the city

economy — usually from non-English speaking backgrounds. They are

hungry to learn the language, though — not to read Milton and join the

Anglosphere but simply to get a job.

They are too well-off to be satisfied by the rural employment

guarantee programme but too poor to be genuinely middle class. They see

themselves as socially underprivileged and perceive their progress to be

thwarted by an elite that has shut the gates and framed complicated,

impossible rules for entry — for professional advance as much as

political office — that usher in only the initiated. Remarkably

hamhanded in their politics, the Congress and the UPA allowed themselves

to be seen as the embodiment of this elite.

Modi’s voters make for a complex set of emotions.

There is undeniable ambition here, completely justified for

talented people who have simply not been given the opportunities they

deserve. There is also a degree of resentment and an anger, sometimes

overdone. Yet, it is equally true that this cohort, this middle India,

represents a far greater section of the Indian population than the

narrow apex of the pyramid that surrounds the Nehru-Gandhi family,

constitutes its reference points and writes its policies and legislation

in chambers in Delhi.

In that sense, this class divide is not between Bharat and India — it is between Delhi and the rest of the country.

Such a binary has caused upheaval in other societies as well. In

several countries of Africa and Asia, the first generation of genteel

post-colonial leaders and elites usually gave way to more angular native

(or nativist) politicians who grasped popular hopes and fears more

easily simply because they had lived these themselves. India has been

lucky and has landed on its feet. It has accomplished a similar change

through the voting machine.

Where other second-generation leaders of post-colonial societies

can be populist and even dictatorial, Modi is cut of a different cloth.

He has been schooled in Indian democracy and sculpted by a decade

of tests in governance and storms in politics. These have made him an

economic change-agent, not an economic waster; these have made him

authoritative, but not authoritarian. Fifty years after Jawaharlal Nehru

died, in the very month, Narendra Modi may as well have inaugurated

India’s second Republic. – See more at:

http://www.hindustantimes.com/comment/analysis/modi-may-be-inaugurating-india-s-second-republic/article1-1220071.aspx#sthash.HQizgfEB.dpuf

In the early 1990s, three social

trends came to capture political imagination in India. There was the BJP’s

ascent on the back of Hindutva, of Hindu anger, prejudice and assertion.

There was the Mandal project that

symbolised the political empowerment of the OBCs, particularly in north India,

a phenomenon later extended to Dalit pride by Mayawati and the BSP.

….

Finally,

there was liberalisation and economic reform, the explosion of expectations and

the politics of growth. Mandir, Mandal and Market: So often in the 1990s,

political assessments in India resorted to that lazy phrase.

Narendra Modi’s dramatic rise to

power in 2014 and the impressive mandate he has won have made that three-way

split and that careful separating of one motivation from another completely

redundant. He is a Hindu leader and mascot. He is an OBC from a traditionally

underprivileged caste background.

He is also the most passionate

advocate of market-based solutions, of enterprise and of the energies of the

citizen — as opposed to the eviscerating qualities of statism — that mass

politics in India has seen in a long, long time.

There is no point arguing whether

Modi would be Right-wing or capitalist in a western economic context, and

whether he agrees with every semicolon of Milton Friedman and every paragraph

of Margaret Thatcher. He doesn’t; but he shares their essential instincts and

buys into their broader logic much more than any other mainstream and electable

political leader in India today.

While Modi has made those abstruse

debates about an ideological battle between three (or more) ideas of India seem

silly if not irrelevant, what has he actually introduced and brought to the

table? The principal appeal of Modi in contemporary India is not religion or

caste or even hyper-nationalism.

It is class. The narrative of a

self-made man, of the son of a father who sold tea at a railway station and a

mother who went house to house washing dishes to pay school fees for her

children, is a compelling and extraordinarily powerful one.

If this election was about Modi

capitalising on a class revolt, that expression has to be understood. The

reference here is not to class in a Marxian sense.

It is simply to primarily young,

small town, semi-urban people — or even rural folk, exposed to or associated

with city life and the city economy — usually from non-English speaking

backgrounds. They are hungry to learn the language, though — not to read Milton

and join the Anglosphere but simply to get a job.

They are too well-off to be

satisfied by the rural employment guarantee programme but too poor to be

genuinely middle class. They see themselves as socially underprivileged and

perceive their progress to be thwarted by an elite that has shut the gates and

framed complicated, impossible rules for entry — for professional advance as

much as political office — that usher in only the initiated. Remarkably

hamhanded in their politics, the Congress and the UPA allowed themselves to be

seen as the embodiment of this elite.

Modi’s voters make for a complex set

of emotions.

There is undeniable ambition here,

completely justified for talented people who have simply not been given the

opportunities they deserve. There is also a degree of resentment and an anger,

sometimes overdone. Yet, it is equally true that this cohort, this middle

India, represents a far greater section of the Indian population than the

narrow apex of the pyramid that surrounds the Nehru-Gandhi family, constitutes

its reference points and writes its policies and legislation in chambers in

Delhi.

……

Link(1): john-kerry-just-visited-but-should-we-just-forget-about-india

Link(2): modis-focus-on-indias-neighbours-is-welcome-but-he-must-not-ignore-the-west/

Link (3): modi-may-be-inaugurating-india-s-second-republic

……..

regards