British East India Company signaled the end of Purani Dilli…..For over 200 years the Red Fort and neighbouring areas housed both

Mughal nobility and ordinary citizens…..The capture of Delhi in 1858 led to Shahjahanabad being changed forever…..city was torn apart by the British….Muslims were hounded out….their properties looted and destroyed…..

……

…….

From the (mythical???) all-glass capital of Indraprastha (Pandavas, Mahabharata) to the modern times and modern-day New Delhi, the valley marked by the Yamuna river to the east and the Aravalli hills to the West and South-West has been privileged as the seat of political power in India.

…..

…

Take any train that terminates in the old (original) Delhi station (for example, Mussorie Express from the eponymous Hill Station) and at journey’s end you cross the river and trundle past the magnificent Red Fort. You will not easily forget the experience (we promise).

….

….

Shah-Jahan-abad is being gentrified one public toilet at a time. We would not really recommend shopping in Chandni Chowk. Try Pahar-Gunj instead, for cheap hotels and cheap finery, a brief walk from the New Delhi Railway terminus (modern one). The Delhi Metro is a wonderful thing, so you can get lodgings in posh Ramakrishna Puram (RK Puram) or Vasant Vihar and still manage to catch the sights, sounds (and most importantly flavors) of the old city. But remember what the old lady had warned about- please be home by night-fall.

…….

After over seven years of bureaucratic apathy, confusion,

indifference and lack of long-term planning to revive the once Mughal

capital, work on the redevelopment of Shahjahanabad has begun.

The name ‘Shahjahanabad’— the place itself laid out by the Mughal

Emperor in the middle of the seventeenth century—might conjure romantic

images of a bygone era, but the reality is far more cruel. A walk down

Chandni Chowk makes this no easier to accept. Except for tourists, both

foreign and domestic, most of those in New Delhi look down upon Old

Delhi as a crowded and noisy place that is best avoided.

Their lack of

an emotional connection with a part of the city that was for over 200

years the actual capital can be blamed on the fact that successive

governments of independent India have looked at Shahjahanabad the same

way it was viewed by the British colonial government.

…

From the Red Fort, one has to cross the busy Netaji Subhas Marg

towards Gauri Shankar Mandir; hopping over piles of garbage and pools of

urine that have leaked out of broken public urinals and onto the uneven

and broken pavements that have long since given way under pressure of

encroachments and temporary stalls selling everything from unbranded

inner-wear to footwear and flowers. One has to negotiate one’s way while

getting elbowed by eager buyers, pushcarts and rickshaws, with motor

cars honking wildly to get past the chaos and confusion under the

decaying facades of Mughal-time and Art-Deco structures made uglier by

the hoardings and billboards of umpteen commercial outlets.

…

In 1911, King George V announced that the capital of British India

was to be shifted away from Calcutta, at an extravagant Delhi Durbar

held in what is now Coronation Park next to Nirankari Sarovar in north

Delhi.

The monarch had desired that a new capital—called New Delhi— be

built, one that would be contiguous with the Mughal city of

Shahjahanabad. His wish, however, was never fulfilled as the team of

architects found the area in north Delhi marshy and full of swamps. They

instead suggested that the area around Raisina and Malcha be developed

into the new capital.

But, even as New Delhi arose in the 1930s, Shahjahanabad remained the

main shopping area for Indians living in the city, while the upcoming

Connaught Place would have stores selling imported food and wines to

English administrators. New Delhi looked antiseptic and devoid of colour

and life.

My mother, now in her mid eighties, recalls visiting Chandni

Chowk with her own mother in the early 1940s, travelling from Pusa

(where her father was heading the Imperial Agriculture Research

Institute), to shop for clothes and groceries. “The driver was

instructed to get back to Pusa before sundown as the area between Old

Delhi and Pusa was a jungle where jackals and hyenas lived,” she

recollects.

….

The end of Mughal rule hastened the end of Shahjahanabad in many ways. ‘Dilli’,

the capital of Mughal India, would soon witness a brutal transformation

that would not just change its demographics but also its geography,

social norms, language and cuisine. In a sense, the victory of the

British East India Company signalled the end of the primacy of what has

come to be known as Old Delhi or ‘Purani Dilli’ today. For over 200 years before this change, the Qila

(renamed the Red Fort) and the neighbouring areas that housed both

Mughal nobility and ordinary citizens, together with the kilometre-long

Chandni Chowk from the Qila to Fatehpuri Masjid, had been the veritable centre of India.

….

The capture of Delhi in 1858 led to Shahjahanabad and Chandni Chowk

being changed forever. The city was torn apart by the British army and

its administrators as they unleashed a vendetta against the people.

Makeshift gallows in front of what is today the Sis Ganj Gurudwara were

set up, and large numbers of men, both Hindu and Muslim, were hanged for

their ‘complicity’ in the uprising of 1857. Muslims were hounded out of

the Mughal city and their properties looted and destroyed, while many

mosques were ruined. A few that were spared—like the Fatehpuri Masjid—

were sold off to Hindu traders like Lala Chunna Mal.

….

The exodus of a large number of Muslims from the Chandni Chowk and

Chawri Bazar areas saw Hindu traders buying and then occupying their

properties. In the early decades of the 20th century, a loan waiver

announced by the government of undivided Punjab led many Hindu traders

to settle down here as well.

…..

According to official records, most of the British officers stationed

at the Red Fort garrison sought early retirement after this posting.

Being posted at the Qila meant that treasures like royal

turbans, illustrated manuscripts, royal furniture and the like were all

up for grabs; and officers and soldiers had the entire fort and its

palaces at their mercy. After the Red Fort was pillaged and royal

artefacts looted, auctions were held for days on end in what is called

Meena Bazar today.

….

The palace of the last Mughal ruler, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was

demolished along with several other buildings; and in its place was

built an army barracks, which, until recently, was occupied by Indian

Army soldiers. A visitor to the Red Fort today will see standalone

buildings that remain disconnected and offer little idea of what a

thriving royal city was like.

Few know that not a single piece of paper

was left by the British that either mapped or located the royal palaces

inside. Even the Diwan-i-Khas, where Mughal emperors once sat on the

Peacock Throne and presided over an empire that included most of modern

South Asia, was first converted into a courtroom for the trial of Zafar,

and later, to denigrate the memory of Mughals, converted into an

Officer’s Mess. Sepia tinted photographs of the period chronicle the sad

decline of the Fort.

….

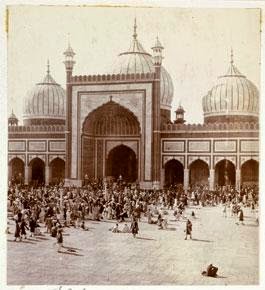

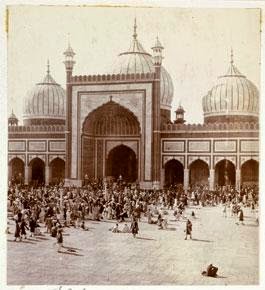

Even outside the fort, the character of Shahjahanabad was changed

when the minarets of the mosques that dotted the skyline were pulled

down one after the other. Some overzealous Englishmen were keen to pull

down the Jama Masjid as well, to build a Christian cathedral in its

place. While Muslims remained persona grata in the area for

over a decade after 1857, Englishmen themselves fancied the vast

courtyards of Jama Masjid as a probable party area, holding frequent

evening parties and balls.

….

Documents well preserved in a little known building of Delhi’s

Archives reveal the city redevelopment that the British had planned.

Official orders of the Delhi Commissioner dating to middle of 1858 state

that Darya Ganj and Dariba (areas containing silverware shops) were

drastically altered. Shops and encroachments were cleared to make way

for roads.

In fact, the road in front of the Red Fort was created after

the capture of Delhi. Soon, the road connecting the Red Fort to

Fatehpuri Masjid—now called Chandni Chowk—was targeted for a makeover.

Divided into four parts (Urdu Bazar, Phool Mandi, Jauhari Bazar and

Chandni Chowk), the area boasted single storeyed shops on either side of

a tree lined water channel. This is the place where Mughal nobles went

to shop in the evenings, and according to an English traveller writing

before 1857, cheetahs and handsome boys were on offer for nobles to buy.

….

The water channel was covered up to ease movement of traffic, while

the octagonal pond was demolished. In its place came up a clock tower

and, in true Victorian style, a railway station that took shape on the

ruins of a royal garden right next to the Red Fort. The beginning of the

Calcutta-Kalka train service in 1861 and the building of a railway

station changed the skyline and look of the medieval city.

….

The introduction of trams soon saw tracks criss-crossing what we know

as Chandni Chowk. Gurbaksh Kaur, now in her eighties, recalls the

excitement among students as they hopped onto modern trams and visited

Paranthe Wali Gali to tuck into stuffed paranthas. Two of the eateries still selling paranthas

are over a hundred years old and find prominent space in tourist

brochures, but this trip is not for the faint hearted as the rundown

look of the area is hardly inviting.

….

Over the years, Chandni Chowk and other historic areas have been

allowed to degenerate. Unlike many old cities across the globe where

both government and local communities join hands to preserve and

conserve the past, there has been no such success here. The

Shahjahanabad redevelopment plan needs to ‘think local’, and municipal

agencies need to be made accountable. After all, basic cleaning services

do not require any parliamentary or executive decision. Shopkeepers

have to be made responsible for waste disposal, pavements have to be

repaired and made user-friendly.

Unlike VIP areas controlled by the

NDMC, which, flush with funds, re-lays pavements regularly to justify

its budget, Chandni Chowk has quite possibly never seen basic repair

work take place despite tens of thousands of people visiting and living

in the area. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has rightly identified garbage disposal

as a major challenge, and the Government has promised to take steps to

boost tourism. Chandni Chowk, visited by every tourist entering Delhi,

could be the place to start with.

Like in the UK, India needs stringent

laws on heritage conservation and the creation of a single window agency

for locals who need to rebuild in heritage areas. The exteriors of

buildings in Chandni Chowk need to be restored and protected; and for

this, any rebuilding or renovation required should be allowed within

reason, in keeping with the requirements of modern life. This has been

successfully undertaken in historic London. In this manner, the historic

nature of the area and its buildings would be preserved while letting

people living within it create new spaces.

….

The absence of public toilets needs to be addressed as well. Many a

foreign tourist can be seen clicking away at men lining up outside a

rundown urinal at Chandni Chowk where little is hidden from public view.

….

At the same time, surely no Delhiwala or Indian proud of her heritage

would like the more-than-300-year-old city of Shahjahanabad to be

replaced by hideous multi-storeyed commercial buildings. Government

intervention and strong accountability are urgently needed. Excuses of

population density and pressure from the local business community cannot

be bandied about by corrupt, inefficient and incompetent government

agencies while an important slice of India’s heritage is destroyed.

…..

Link: http://www.openthemagazine.com/article/nation/power-and-glory

…..

regards