This post was inspired by an earlier post of X.T.M where he mentioned that this question generates a lot of traffic for BP.

If we consider the literal definition of Paganism, the question becomes quite simple. Historically, the term “Paganism” was not used to describe religious beliefs prior to the 20th century. It first emerged in the context of Early Christianity, serving as a pejorative for the folk religions still practiced in the rural regions of the Roman Empire. By this definition, it’s clear that Hinduism does not fit the label of Pagan.

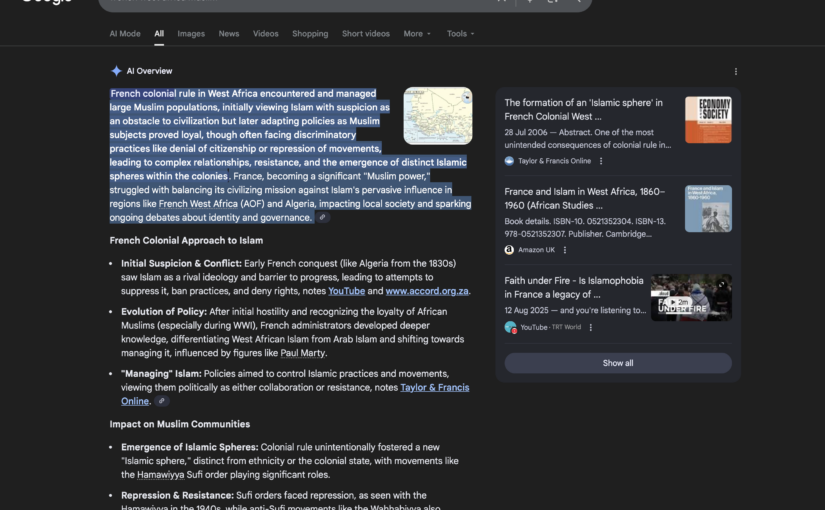

However, in contemporary usage, many Neo-pagans view Paganism as a neutral descriptive term, applicable to all cultures that are philosophically incompatible with the three Abrahamic faiths. The question whether Hinduism can be considered Pagan in this broader sense is not so simple since most Hindus assert belief in a singular God or multiple manifestations of one God (30 percent and 60 percent, according to PEW surveys).

To start answering this question, we need to pinpoint the philosophical foundation of Hinduism. Thankfully, this isn’t too complicated, as several Vedic verses touch on this theme (e.g. Brihadaranyaka 4.4.18 and 4.4.22), all leading to the same conclusion. These verses indicate that the essence of all spiritual paths in ancient India revolves around Adhyatma (the doctrine of enlightened self). The central concept of Adhyatma is Atman—an ancient, observer consciousness believed to be deeply embedded within each of us. The ultimate aim is to attain Moksha, i.e. to awaken and realize this concealed enlightened self. Now, if we were to bring the God of Abraham and Atman together on a talk show, asking them to explain their doctrines to the audience, it might go like this:

God : I am the all powerful God.

Atman : I am your peaceful inner self.

God : I am the true creator of everything that you perceive.

Atman : I am the true experiencer of all that you perceive.

God : Submit to me unconditionally and obey all my commands.

Atman : Become one with me and be liberated.

God : If you are loyal to me I will take to heaven after you die.

Atman : Whenever you see yourself as me, the Earth looks like heaven.

God : Initiate force against others if they oppose your faith.

Atman : Mix with others if they oppose initiation of force.

Even in these highly simplified versions one can clearly see that the Atman doctrine is Pagan if we apply the more inclusive definition of Paganism. It can also be viewed as a branch of Pantheism. In Adhyatma the analogue of impersonal supreme God is Brahman, the entire universe seen from an enlightened perspective. Since experiencing Brahman is same as experiencing one’s Atman, many experience oriented spiritual traditions use them as interchangeable terms. So when Hindus talk about one God, the are referring to the impersonal God, not the God of Abraham.