What’s up?

What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?

What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?

This is the Immortal quote from arguably the greatest book written on any sport, in this case, cricket from “Beyond the Boundary” by CLR James. This was obviously inspired by Kipling’s poem, “The English Flag “where he asks “And what should they know of England who only England know?” to celebrate the British Empire’s global reach. James says what he said to convey that it’s always in one’s interest to evolve and never stagnate. I was thinking about this after today morning’s seemingly bitter argument between two friends in one of these ubiquitous cricket themed WhatsApp groups about the primacy of IPL versus Test cricket with the conversation getting increasingly heated and personal. I am assuming thousands if not more such groups will be having similar debates and wanted to think this aloud – I don’t expect any brilliant new insight to emerge but sometimes writing this out may clarify our collective thoughts, or that’s the aim!

At the outset, comparing the two formats is blasphemy, one is a 150-year-old sporting institution with a rich history and legacy and IPL is a15 odd year young upstart that shocks the purists. A lot argue that these two are in fact two entirely different games. I wouldn’t go as far as that but let us see where they get together and where they differ.

Tests with their ebbs and flows almost mirror life, you lose the toss and have a disastrous first session, why the whole first and second day as well or like the first test in the England series that concluded recently, be behind the match so much but still Pope scores an all-time great or freak innings and England win. That causes all of us tragics to rant and rave but suddenly India turns up and beat them 4-1. Or the last Australia series where after the 36 all out ignominy of Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney and Gabba became classics for the ages! Similarly, all the Ashes rivalries, Bodyline Series, India Pakistan test matches and so on, each cricket lover will have 20 test matches close to their heart for a variety of reasons.

IPL in contrast is an Indian Bollywood like affair with auctions, mix and match of foreign and Indian players, owned by celebrities – Movie stars and businessmen and rules like Calvinball , sort of made up as we go along the tournament over the years . The impact player in the last 2 versions is an example – last year it was a novelty. This year the think tanks of the teams have got a plan to exploit it and we have seen an immediate impact already – scores of 270 plus are common and we may see a 300 soon. The theory is having an additional hitter mentally frees up the other batsmen to bat more freely than they may otherwise. Is this tinkering with the basic structure of a playing eleven – sure it is! However, the crowds love it and so we enjoy the hitting and feel mildly sorry for the bowlers. The cult following of certain teams ( CSK – my team!) is something else. Anyone who has been in the ground at Chepauk especially if not any ground when MSD Dhoni enters to bat this year will have an experience of a lifetime!

Has the IPL rubbed off positively on the traditional form of cricket – Tests? Let us examine the evidence. The scoring rates of tests this millennium is way higher than it was ever before. The number of draws is also very few and far in between and mostly we see a draw only in case of a weather exception. (The Sydney- one arm and one leg Horatio Nelson like stand of Ashwin and Vihari being a glorious exception!). It has also enabled batsmen to be way more adventurous in tests – Rishab Pant reverse scooping Jimmy Anderson in a test and Bumrah using slower balls to get Bairstow out in tests in England come to my mind. There are numerous such examples where the innovation, cheekiness and variations of the IPL are brought on to the test matches making them exciting. New talent from the hinterland is unearthed, the kids make their name and fame in IPL and do well for their countries in tests as well. Jurel being the latest case in point. Fear of losing and playing under huge pressure with a lot of crowds is something young Indian players learn very young to adapt and that stands them in good stead in tests too. range and power hitting as seen by the Indian youngsters as well as foreign players and the 150 km and more speeds cranked up by young bowlers is a treat to watch !

Is it all roses then and IPL has no faults? The age-old virtue of grinding out a session appears to be a bit lost but there are still players like Pujara who do it to great success ( He does not play much of IPL or no one selects him much !) . Much was made of the Bazball hype by England but when all all-time great test batsman like Joe Root reverse scoops Bumrah to the slips when the series was in balance , the idea lost its hype I would imagine even though the English and their cloying press still cling on to it. The Ashes later this year should settle that argument once and for all!

From Indian cricket point of view, there has been interesting ramifications. In Tests since the inception of IPL, the Indian test team for most parts has done exceptionally well, have been the no 1 test team for long periods of time, have won two away series in Australia and only South Africa has been the last bastion yet to be conquered. However, we have lost both the WTC finals, on the face of it that cannot have anything to do with IPL. More worryingly after 2008 we have not won any ICC white ball trophy, the cruelest cut being the final we lost to Australia last year at Ahmedabad. I do not fancy much our chances in the T20 WC as well later this year in the Americas. Can this too be correlated to IPL – let us see what is the evidence again if any.

One worrying trend is players prioritizing IPL over national duty – classic case seems to be Hardik Pandya, I do not remember him missing any IPL but in national colors, he seems to twist an ankle or pull a muscle even while sneezing. While the Aussies seem to have a party at the IPL almost appear to take it as a lark , earning big money in millions while in national colors, they seem to give their blood and more to win. Maxwell being the case study for this, RCB his team is the butt of a million memes and he does precious little for them on most occasions while for Australia he plays impossible knocks to win them tourneys! I cannot think of any Indian player like that while like Pandya we may have several examples. Similarly the IPL spin offs owned by the same franchises have undermined test cricket in other countries as well. South Africa sent a third XI to New Zealand to play a test series as their main players were busy with their version of the T20 league. This can be explained away as a scheduling issue, though players can only play for so many days in a year and need to rest and recuperate. The balance between the pride from national Duty to the commercial windfall from T20 leagues is a tricky one. BCCI to its credit has tried to address this by specially incentivizing players for test wins, though the other boards may not have the financial muscle to do that.

IPL has done a lot to popularize cricket with women and children, it has brought a new demographic who hitherto were cold to cricket and made them follow the game and its nuances. Sure, it can be described as a pure tamasha but the basic skills of the game are on display and the next generation is getting hooked on to the game. Given cricket was always a game played by a handful of countries this is important for the game to survive for the next 50 years and more. There was a recent survey in India amongst kids younger than 10 years and for the first time ever football was rated as the game that they followed or played most! That means IPL is necessary for even tests to survive in a manner of speaking.

In summary IPL has its utility, it is more entertainment than pure sport but some elements of the sports are sharpened due to it and the benefits spill over to make the oldest format of the game, test cricket, more interesting. The caution is young players prioritizing one for the other, it is perfectly fine that a young player prefers IPL over national test duties but the commercials and risk reward mechanism should be structured in such a way that the decision does not become a heavily skewed one to favor League Cricket . We still will have a Bumrah , a Rishab Pant and a Travis Head making an impact in all formats of the game and entertaining us !

Modi 3 and the fruits of fiscal Tapasya

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

Modi does the unthinkable – goes to polls with a non-populist (revdi-free) budget

At the start of this year, I had written about Modi’s excellent economic stewardship during his second term amidst a period of extreme economic turbulence globally – a once-in-a-century pandemic followed by a major war which roiled energy markets and rapid rate hikes in the West to combat inflation (Modi’s fiscal masterclass). I had noted then that Modi:

“has achieved the near impossible of following a disciplined fiscal policy while not just maintaining his political capital, actually expanding it”

But I had fully expected that he would open up the purse strings during the election year budget this February notwithstanding his public remonstrations against the growing revdi (freebies) culture. And for good reasons. One, Modi had gone in for a ‘revdi’ at the end of his first term in 2019 (the cash transfer scheme for 120 million farmers). And the economic scenario in 2024 was decidedly more mixed compared to 2019 with greater level of economic distress among the poor. Two, recent state elections had seen parties winning based on extremely aggressive freebie promises. For example, Congress won handsomely in Karnataka last year with promises of a slew of freebies (or welfare programs if you like) amounting to more than 2% of the state’s GDP. So I must not have been the only person who was stunned to see that Modi had decided that the normal rules of politics does not apply to him. And as of today, his judgment appears to be spot-on because the only debate about the 2024 elections appears to be what his margin of victory will be. The reasons for this – the so-called “akshat-wave” after the Ram mandir inauguration, the opposition being in absolute shambles, the ever-increasing political stature of Modi – calls for a separate discussion. In this post, I peer into the future and see what Modi’s fiscal statesmanship could potentially mean for the country.

A 10-year long fiscal tapasya….

For reasons that are not entirely clear, fiscal conservatism has been an article of faith for Modi throughout his career as an administrator. He has held on to it steadfastly during his entire 10 years as the the Prime Minister. For anyone familiar with Indian politics, it is easy to appreciate how challenging it can be to stick to fiscal discipline even during times of buoyant revenues. This makes his unrelenting fiscal focus all the more remarkable considering that for most of his tenure, he has been hemmed in by weak tax revenues. Therefore, to call Modi’s 10 year long commitment to financial discipline as a tapasya (penance) would not be out of place.

…might finally yield a Rs.20T (~$50bn) -sized fruit during Modi-3

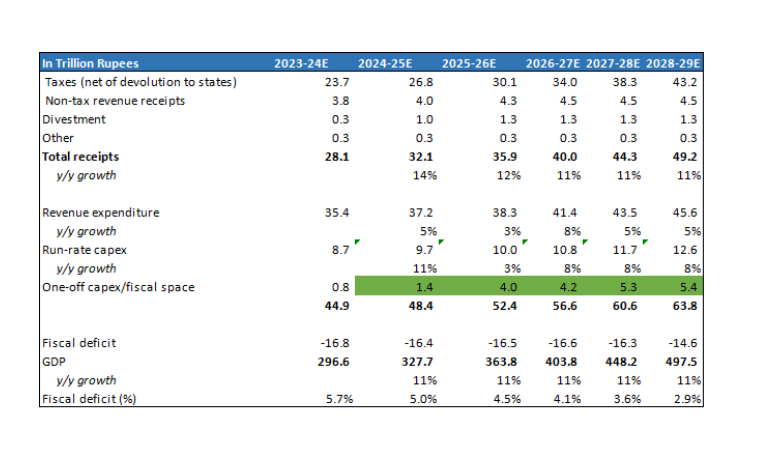

And Modi is on the cusp of reaping the fruits of that tapasya in his third term. Barring unexpected shocks – electoral and economic – he could be presiding over a period where the economy has sizeable fiscal resources to pursue its socio-economic goals; a rare event in independent India’s economic history. Underpinned by a solid cyclical recovery in the economy and strong buoyancy in tax collections (direct taxes likely grew at 20% in 2023-24, twice the pace of nominal GDP growth), Modi-3 is not only placed very comfortably to meets its 2025-26 fiscal deficit target of 4.5% (vs. 5.8% in 2023-24), it will also have its disposal, up to Rs.4 trillion of fiscal space during 2025-26 for spending on new programs or projects (or >1% of GDP) after meeting its regular revenue and capital expenditure obligations. That is the base case which assumes direct taxes grow at 15% annually. In a bull case of direct taxes continuing to grow at 20%, the above figure could be as high as Rs. 5.5 trillion. Further, this figure will continue to swell with each succeeding year as the economy expands and revenue growth outpaces the growth in base expenditure. During Modi’s third term, I estimate that the central government will have up to Rs.20 trillion of aggregate fiscal space for new programs/projects. Also, note that many of the programs of the central government include contribution from the states, which means the total fiscal resources available could be well higher than Rs. 20 trillion.

(For those interested in the math behind the above numbers, I discuss the same at the end of the post) .

Potentially transformative, but availability of funds is not enough

What can one do with an annual budget of Rs.4 trillion? Well, for perspective, the Jal Jeevan Mission which was initiated in Modi’s second term with an annual budget outlay of Rs.0.7T (Rs.3.5T over 5 years, 60% funded by centre) will have provided tap water connections to 160 million households by end of 2024 (110 million connections provided as of April 2024). No commentary required on how transformative this project has been for the 100s of millions of beneficiaries.

In the first two terms, Modi’s focus was primarily on building physical infrastcucture – road building under Gadkari has been an unqualified success while in case of Railways, huge investments have been made, it is still a work-in-progress with mixed results so far. Even welfare schemes had a physical asset bias – from toilets to piped water to housing. While the government deserves a lot of credit for strong execution, it has to be underlined that these are relatively low-hanging fruits from a governance perspective. As the priority areas inevitably shift from road and railways to more complex ones, quality of policymaking, human capital and management will be the key drivers of outcomes, and not just availability of funds. To wit, it is way more difficult to develop 20 high quality IITs or a few hundred Kendriya Vidyalayas compared to building 100K kms of roads. Or just throwing around money into PLIs will not deliver a successful industrial policy.

An opportunity for Modi to cement his legacy – a wide range of focus areas to choose from

What areas Modi will prioritize with the Rs.4 trillion per year (~$50bn) of additional resources is anyone’s guess because this is one government which revels in keeping its plans a total secret. One can only say two things with certainty -one, Modi will be extremely keen to cement his legacy with a couple of flagship projects/programs which has a transformational impact on society. Two, the consummate politician that he is, he will have his eyes firmly on what programs will drive the optimal political benefit for the 2029 elections (and all the state elections over the next few years).

The list of potential programs is endless. Below, I discuss briefly a few ones which I see as critical ones. I classify them into 3 categories: A) long term strategic B) medium term economic growth and C) quality of life. Obviously, most of these programs will tick all three boxes, the classification is based on how a politician like Modi would want to see it. Admittedly, some of the resources might also simply get used up in standard fiscal management as well – ie Modi might simply want to reduce fiscal deficit at a faster pace, or execute the long pending reduction on tax surcharges on the rich or fill up the job vacancies in the government.

- Long-term strategic

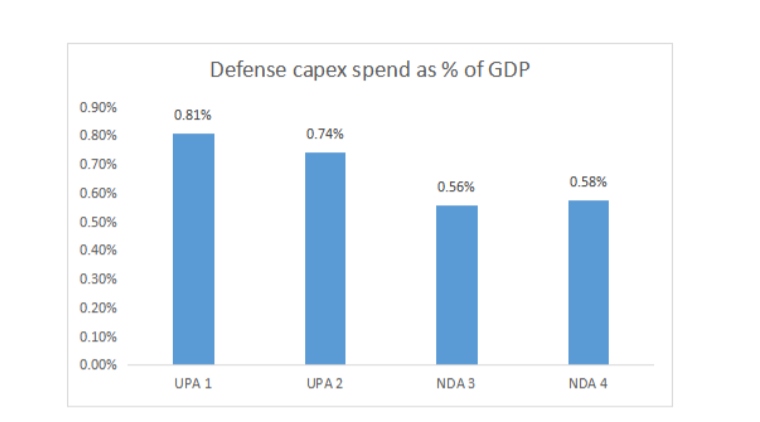

- Increase defense capex spend – In contrast to his public image as a hawk on national security, the the spend on defense capex has been rather modest. In fact, as a % of GDP, it has dropped from the levels seen during UPA. With the China threat escalating in recent years, Modi would want to increase defense capex by at least 10 bps (100 bps = 1%), if not 20 bps and get back to UPA levels. That would be 0.35-0.70 trillion increase in annual outlay.

- Increased R&D spend – India’s R&D spend is abysmally low at around 0.6% of GDP compared to 2.4% for China. The spend has seen a steady decline from the 2008 peak of 0.9% and private sector has shown very little inclination to spend on R&D with their contribution being only around one-third of the total spend whereas in countries like China and Korea, the figure is more than two-thirds. A key policy objective for the government, apart from increasing its own direct spend, should therefore be to bring in major policy incentives to crowd-in private investments in this area. As it happens, the government has already signaled that this will be a priority area in the third term, announcing a Rs.1 trillion fund to provide long-term interest free loans for R&D work. But much more needs to be done.

- Energy security – There are two parts to this. One, as a major importer of oil & gas with demand continuing to grow for the forseeable future, the country needs to own equity in oilfields and LNG plants abroad to enhance its energy security. For example, if India wants to secure say ~20% of the nearly 5 million barrels/d of crude it will import this year, that will mean an investment of $40 billion. Of course, the investment will be done via the government owned oil companies and it will be partly funded via debt. But it might still entail the government infusing a $5-$10 billion of equity.

The second part is investment in energy transition. So far, the Modi government has bet big on solar but now it has also stated its intention of expanding its nuclear fleet (add 15 GW by 2030). While investments in solar power has been largely driven by private players, the government will need to play a big role in setting up nuclear plants. A back-of-envelope estimate for the cost of the plants would be $50 billion and it would be reasonable to assume that the government will have to invest close to half of that amount.

- Medium-term economic growth

- A PLI-powered industrial policy – An easy prediction to make is that a turbo-charged PLI program will be the topmost priority for Modi-3. After all, the biggest failure of Modi- 1& 2 has been the inability to kickstart growth of the industrial sector and deliver well-paying manufacturing jobs to to a burgeoning labor force. Success or failure to deliver on this during the third term will likely be the most consequential factor in 2029. With the success of the modest sized PLI programs so far, Modi will look to bet much bigger sums on the program. But, at the risk of repetition, PLI itself will not be sufficient. A lot more work needs to be done in terms of improving ease of Doing Business, bringing down land costs, labor laws, building a skilled workforce and so on. One specific area where I really hope Modi-3 focusses on is building a vibrant EV industry (nah, not the two-wheelers, cars are the real deal). We are already a few years behind almost every major auto market globally on EVs. If China is the undisputed leader in EVs today, it is because the government has pumped in nearly $200bn into the industry via subsidies, grants and incentives over the last two decades.

- Agriculture – The government would be keen on doing something transformative in this sector, not least because it is still the largest vote bank, but I am not sure ploughing in large sums of money will solve the structural issues bedeviling the sector. Having got their fingers burnt during the second term with the farm laws, it is unclear to me what major policy action they could take up for this sector.

- Quality of life

- Urban housing and infrastructure – Another easy prediction to make is this (especially urban housing) will be one of the biggest focus areas in the third term given Modi’s penchant for physical infratsrructure. The political dividends will be way higher than what he has received for roads since the change will not just be very visible to the average voter, it will also have deeply positive impact on his day-to-day life. Modi has already delivered well on rural housing but urban housing will be way more challenging, not least due to scarcity of land and a large, ever-increasing migrant population. It will require well-thought out policies and mich greater co-ordiation with the state and local governments

- Health and education – The public investment in health and education has been woefully short forever and that trend has continued thru the Modi years. Between the two, I think Modi will focus on health because the political benefits accrue faster and it is also relatively less difficult to execute compared to education. On paper, both these sectors can easily absorb, individually, an additional 0.5% of GDP (I.e. almost the entire Rs.4 trillion fiscal space) given the historical underspend in the sectors. But, more than any other programs, funding is a much lesser factor compared to the ability to build quality organisations which can deliver.

The fiscal math

Assumptions

- Nominal GDP grows at 11% (6.5% real and 4.5% inflation)

- Direct taxes grow at 15% annually while GST grows at 13%

- Divestment (both PSU equity and physical assets) per year of Rs1.25 trillion

Fiscal deficit falls to 4.5% by 2025-26 and below 3% by 2028-29.

A few points:

- 2024-25E total capex was Rs. 11.1T but this included equity infusions to BSNL and funds for the Science Fund which will not be repeated.

- The Jal Jeevan Mission wich has an outlay of Rs 0.7T in 2024-25 comes to and end during the fiscal year, hence lower growth in revenue expenditure in the next year. That, in turn, adds to the fiscal space.

- Run-rate capex is for ongoing projects across various sectors – more than half of it is for Roads and Railways. The assumption is that the allocation to the two sectors have peaked and will see more a modest 8% growth growth forward.

- Higher growth baked into 2026-27 revenue expenditure to factor in 8th Pay Commission.

Modi’s fiscal masterclass

The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

Fiscal management has been one of the most critical parameters for evaluating the central government’s economic governance as far back as I can remember — and I have been a amateur observer of the Indian economy for more than two decades. And not without reason. In the Indian context, fiscal management goes well beyond the classical approach of fiscal as a countercyclical force — i.e. government spends more during economic downturns and dials back when the economy is doing well. For India, there has been a strong case for a structural reduction in the government’s fiscal deficit primarily for the following reasons:

A) The most obvious reason — uncontrolled fiscal deficit can result in a debt trap. The Indian government has already been spending between one-third and half of its total receipts towards interest payments since 2000.

B) The fiscal deficit is funded by borrowings in the domestic market. This in turn, crowds out investment by private sector who are competing for the same funds.

C) High fiscal deficit risks macro-economic instability — high inflation and a Balance of Payments (or foreign exchange) crisis . High government spending flows into higher income for households which drives higher consumption demand. If there is not enough supply, it leads to inflation. If you think about it, it is related to B). It boils down to the fact , in many instances, government spending is not economically efficient and therefore is not generating commensurate economic output.

Indeed, we saw the macro-economic instability play out in UPA 2 as high fiscal deficit contributed to persistently high inflation, an out-of-control trade deficit (imports less exports of goods and services).

That being said, economic theory is not like the laws of physics. There are those who have argued that both During the Vajpayee and Modi years, the governments missed a trick by being too fiscally conservative and thereby stifling growth. But even most of these critics argue only about the scale of fiscal tightening, not the principle itself that fiscal tightening is a good for the long term.

As is to be expected, the ideal amount that any government would prefer to spend is…….infinite. The more a government spends, the more popular it will be with the voters, in the near term at least. Fiscal management for a ruling party, therefore is a tightrope walk between preserving one’s political capital and an economically optimal fiscal policy.

In these series of posts, I plan to analyse Modi’s record of fiscal management during his second term. I posit that Modi has delivered a masterclass in fiscal management — he has achieved the near impossible of following a disciplined fiscal policy while not just maintaining his political capital, actually expanding it. All this, amidst times of high economic turbulence globally. In good part, this is because we have, arguably the most incompetent and out-of-touch opposition since independence. But this is also a story of how a politician put his popularity at stake and took the more difficult economic path and the average voters’ willingness to look past their near term pain due to their abiding faith in the man’s intention (the Hindi word is neeyat, I think) and ability to deliver in the long-term**. That is what it is all about — because let us be honest, Modi has, after all, not delivered all that well in terms of the promise of acche din so far.

**Critics will argue this is because voters are prioritizing Hindutva over economic development. There is some truth to it as well and as a Hindutva supporter, I see it as a good thing. But I believe they are exaggerating the Hindutva factor but that is a separate debate.

Fiscal deficit is simply the difference between the total expenditure of a government and its total receipts. This is typically measured as a percentage of GDP.

Both expenditure and receipts are classified as revenue and capital. A capital expenditure is something which results in the creation of a long term asset — a road, a railway track, a port and so on. Spend which does not result in a long term asset is revenue expenditure — things like salaries for government employees, fertilizer subsidy given to farmers, interest on borrowings etc. Revenue receipts are primarily either taxes or dividends from government-owned companies or from RBI. Capital receipts are inflows from divestment of government companies, sale of telecom spectrum etc.

Revenue deficit is the revenue expenditure less revenue receipts. Again, this is measured as a % of GDP.

Total debt as a % of GDP is another key measure of fiscal management, which is self-explanatory.

Internal and Extra Budgetary Resources (IEBR): The government can also spend money outside its budget books via the companies that it owns. For example, if NHAI takes a Rs. 1 lakh crore loan to build roads, that borrowing will not be reflected in the government’s books. But ultimately the government is responsible for the debt, so it needs to be factored in.

Quality of spend — revenue vs capital expenditure

It is generally understood that, in the Indian context, the government should be spending more on capex considering how deficient we are in terms of infrastructure. And on the other hand, contain revenue expenditure which is a less efficient use of fiscal resources. But this is just a high-level view and I will have to warn upfront that not all revenue expenditure is bad and not all capex is good. For example, this government is spending 70K crores this year on Jal Jeevan Mission — all of this is revenue spend. On the other hand, the government has allocated over 50k crores as capital infusion to BSNL. Difficult to argue that this is actually for the creation of productive assets and not just covering the losses an inefficient public sector operator.

But for a big picture view, we assume that capex spend is qualitatively better and then as I drill down further, we look more closely at the specific areas of spend.

What is good fiscal management?

Tax revenues, which constitute the bulk of total receipts, are generally a function of the economic cycle. The government can, of course, raise or lower tax rates. Further, in the Indian context, growth in tax revenues also reflects on the effectiveness of the government’s taxation policies and administration in bringing in greater formalisation of the economy (what is called bringing black money into the tax net, in popular parlance).

Most of the revenue expenditure is either non-discretionary or semi-discretionary. Whether the economy grows 8% or declines 6% (like in 2020–21), one will have to pay the salaries, service the debt and so on. Even spend that is discretionary on paper, is de facto non-discretionary. No political party will touch the fertlizer subsidy, for example. Further, there is constant political pressure to increase revenue spend because that is an easier way to reap political dividends. On the other hand, while capex is discretionary, it is also critical for the long term.

The performance should therefore broadly be judged on the following parameters:

A) What is the overall level of fiscal deficit? With the caveat that it should be seen in the changed global context due to a once-in-a-century pandemic.

B) Receipts growth and especially tax buoyancy — ie how much has tax collection growth out/underperformed economic growth?

C) Quality of expenditure — Ability to keep revenue expenditure in check and focus resources on capex.

But I cannot emphasize enough that good fiscal management is the ability to balance the above political vs economic imperatives in an optimal way. A good example of how not to do it was provided by the BJP government in Karnataka which went to polls last year boasting of a disciplined fisc and record capex allocation, only to be swept away by the voters who chose the opposition party which announced a slew of pro-poor welfare measures (or freebies or revdis, as critics would call it).

Alright, now we get down to the numbers. Here, I analyse Modi’s fiscal management at a high level for the period 2019–20 to 2023–24. Keep in mind that we had a major global pandemic which dramatically pulled down economic growth the world over and this also meant governments had to expand their fiscal spend substantially. So fiscal metrics go awry — higher numerator and lower denominator (i.e. GDP).

Fiscal deficit expands, as pandemic hits growth

Modi started his second term with a fiscal deficit of 3.4% (2018–19), which was quite moderate then, but looks like an unreal number in a post-pandemic world. The number is also low because a good part of the spending was done via IEBR (ie outside the budget books). He will end the term with a fiscal deficit of close to 6%, which is a pretty good performance overall, considering how the pandemic has ravaged public finances worldwide.

GDP during the period grew at just 4.2% annually. If expenses grow faster than GDP growth, it leads to a widening of fiscal deficit while if it is slower, it leads to a reduction. The converse is true in case of receipts. As you can see in the table below, receipts grew only modestly faster than GDP, so the widening of the fiscal deficit is largely attirbutable to higher expenditure.

Note: 2018–19 GDP has been indexed to 1000 and all figures are based on real growth (i.e adjusted for inflation)

Budgetary capex spend grows sharply

Next, we drill down to the expenditure. What do we find? Both revenue and capital expenditure has outpaced GDP growth but it is capex which has grown at a furious pace. But since revenue expenditure accounts for more than 4/5 of total spend, it contributes to 100 bps (100 bps = 1%) of the widening in fiscal deficit while capex contributes to 170 bps.

Capex spend trend solid even after factoring in IEBR

But wait, the capex growth is not as dramatic as it sounds. A large part is simply because Modi government moved from IEBR to budgetary support for road and railway capex. Combining both budgetary capex and IEBR spend, the numbers still look pretty solid though. Optically, it increases only by 20 bps to 5.0% but 2018–19 was also an extremely strong year for capex spend. If one compares the overall capex spend for Modi’s first and second term, the trend of improving capex spend is clear. And this is during a period of aneamic revenue growth.

The fiscal masterclass — strong discipline in revenue spend (ex-interest)

Drilling down further into revenue expenditure, we find that the increase in spend has been entirely driven by higher interest expense. This is because, like most other governments, India had to suffer big fiscal deficits in the first two years of the pandemic — so higher overall debt levels. This was further exacerbated by rising global interest rates.

Excluding interest expense, revenue expenditure has actually been a net positive for the fiscal deficit, moving down by 40 bps. This forms the crux of the fiscal masterclass that I keep referring to. In a period of economic turmoil, Modi government has been able to hold the line on revenue spend, amidst immense political pressure for populist measures. Revenue expenditure (ex-interest) annual growth was contained at just 3.2% — we will drill down further on this later but this low growth is despite significantly higher outlay for food subsidies and the Kisan DBT (2019–20 was first full year of the program).

Receipts — modest growth supported by high fuel taxes

Receipts have only modestly outperformed GDP growth though we are finally seeing signs of a turnaround in private sector profits as the sector comes out of the twin balance sheet crisis (high bad loans in banks and high debt levels in businesses). Meanwhile, Modi has held the line with high fuel taxes, inarguably an unpopular decision politically. While it was easier to do when oil prices had collapsed in 2020, to continue those taxes even as oil has moved back to $80/bbl shows great political fortitude. And he has maintained those high taxes with just a few months to go for the national election.

(On a tangent, I have written about why fuel prices should be reduced and it has no impact on the fisc)

Higher fiscal deficit but fiscal internals and outlook positive

To summarize, fiscal deficit widened by 250 bps during Modi’s second term but this was driven by a 170 bps increase due to capex and 150 bps increase due to higher interest expense. Revenue expenditure (ex-interest) actually came down by 40 bps.

Admittedly, a fiscal deficit of 5.9% is still quite high but the government has set itself up pretty well for a meaningful reduction in the medium term. For one, there are clear signs of a corporate profit recovery and strong bouyancy in personal tax collections. Two, the burden of interest expense should keep progressively coming down given an exapnding GDP base. Three, the government has the option of flexing down on capex spending over the next couple of years contingent on a revival in private capex spend.

Counterfactual — what if it was UPA-3 instead of Modi-2

One way to think of the scale of Modi’s achievement is to think where the fiscal deficit would have been if we had a UPA-3 in 2019 instead of Modi-2. How much higher would the revenue expenditure spend have been? And how much lower would the fuel taxes have been? And what that would have translated into in terms of fiscal deficit, inflation and growth. Admittedly, the difference between a UPA-3 and Modi-2 does not just boil down to Modi — a large part is simply because BJP has a majority while UPA would have been an unstable coalition. But, again Modi deserves a lot of credit for running the first non-Congress majority government.

Browncast: Indic Modernity

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

This episode was recorded a month ago, but we had some delay in uploading it, our apologies to Vineet. Vineet is very active on social media and runs the Indic explorer channel on Youtube. Please do check it out for interesting stuff on India. In this episode Mukunda Raghavan and I talk to Vineet about Indic modernity. What is it? what is it likely to become? and so on..

Abhinav Prakash: How Savarkar and the RSS won

A previous discussion on this topic with Kushal Mehra of the Carvaka podcast:

Is Brahmin a controversial word

Brown Pundits on 2024 election in India

Another Browncast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

Omar, Mukunda, Maneesh, Gaurav and KJ have a freewheeling chat on the upcoming elections in India.

The Brown Pundits stick to the prevailing consensus, they don’t see NDA losing this election. View from California and Rawalpindi. A BP bets his shirt on the outcome in one particular state. We wrap up the episode with thoughts on the coverage of India in the western media.

Elamo-Dravidian and the Koraga

Novel 4,400-year-old ancestral component in a tribe speaking a Dravidian language:

Research has shown that the present-day population on the Indian subcontinent derives its ancestry from at least three components identified with pre-Indo-Iranian agriculturalists once inhabiting the Iranian plateau, pastoralists originating from the Pontic-Caspian steppe and ancient hunter-gatherer related to the Andamanese Islanders. The present-day Indian gene pool represents a gradient of mixtures from these three sources. However, with more sequences of ancient and modern genomes and fine structure analyses, we can expect a more complex picture of ancestry to emerge. In this study, we focus on Dravidian linguistic groups to propose a fourth putative source which may have branched out from the basal Middle Eastern component that gave rise to the Iranian plateau farmer related ancestry. The Elamo-Dravidian theory and the linguistic phylogeny of the Dravidian family tree provide chronological fits for the genetic findings presented here. Our findings show a correlation between the linguistic and genetic lineages in language communities speaking Dravidian languages when they are modelled together. We suggest that this source, which we shall call ‘Proto-Dravidian’ ancestry, emerged around the dawn of the Indus Valley civilisation. This ancestry is distinct from all other sources described so far, and its plausible origin not later than 4,400 years ago on the region between the Iranian plateau and the Indus valley supports a Dravidian heartland before the arrival of Indo-European languages on the Indian subcontinent. Admixture analysis shows that this Proto-Dravidian ancestry is still carried by most modern inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent other than the tribal populations. This momentous finding underscores the importance of population-specific fine structure studies. We also recommend informed sampling strategies for biobanks and to avoid oversimplification of ancestral reconstruction. Achieving this requires interdisciplinary collaboration.

Not definitive, but I think this shows the value of greater sampling in Indian subcontinental populations.

A Conversation on Politics in Tamil Nadu

Dr Omar Ali joins me and we talk to K Jayaraman (KJ) on political movements and politics in Tamil Nadu.

KJ talks about the origin of the Dravidian movement, the evolution of the movement to a political force, the decline of Congress and BJP’s chances in the upcoming Lok Sabha elections.

Dharma in the Bhāratīya Frontier – Multan

Carl Sagan famously said that you have to know the past to understand the present. As the inheritors of the Dhārmika civilization, to understand the present, we must go back to where it all began – Mūlasthāna, a place we are guilty of forgetting.

An Old Fort of Dharma

The origin of the great Bhāratīya civilization is widely acknowledged to date back to antiquity. However, the question of which city in the region of Bhāratavarśa has been continuously inhabited for the longest period, remains unresolved. Multan, formerly known as Mūlasthāna, Sāmbapurā, Kāśyapapuri, and Prahlādapurī, is widely believed to be the oldest city in the Indian subcontinent, with an estimated antiquity of 3000-2800 BC according to Ahmad Nabi Khan’s book “Multan: History and Architecture”. This estimation, however, is just a glimpse into Multan’s distant past, as its true age has been muddied by the passage of time. Today, the city of Multan finds itself in Pakistan, following the partition of India in 1947, and for most Indians today, the memory of this city itself has become a hazy one.

Multan was historically a bustling city located at the crossroads of important trade routes. To get a sense of what ancient Multan was like, imagine a city with narrow, winding streets lined with vibrant bazaars, populated by merchants and traders, selling everything from exotic spices and textiles to precious gems and jewelry. The air is filled with the sounds of bargaining and the smell of spices. In the center of the city stands a majestic temple, a symbol of the city’s religious importance. Around the temple are grand buildings and mansions, constructed from gleaming red bricks and decorated with intricate carvings and mosaics. The city is surrounded by high walls, giving it a fortress-like appearance and providing protection from invaders. Beyond the walls are lush green fields, dotted with farms and orchards, stretching as far as the eye can see. The Chenab River flows nearby, providing a source of irrigation and water for the city’s residents. In this ancient city, one can see the blend of different cultures, reflected in the architecture, art, and customs of its people. Ancient Multan was truly a city of great beauty and importance, and a visual feast for the senses.

So, what do Dhārmika scriptures tell us about the origins of Multan? According to tradition, the city was founded as Kaśyapapurī by the sage Kaśyapa, a descendant of Brahma, and the son of Manu. Its ancient heritage is confirmed by numerous archaeological sites in the area dating back to the Early Harappan period of the Sindhu-Sarasvatī civilization. This same city is described as Kaspapuros by Hekatues, Kaspaturos by Herodotus, and Kaspeira by Ptolemy. The Mahābhārata mentions Multan as the capital of the Trigarta Kingdom, ruled by the Katoch dynasty, during the Kurukṣetra War.

Additionally, Multan is considered to have been the capital of King Hiraṇyakaśipu of the Kāśyapa gotra and was later renamed Prahlādpurī after his son Prahlāda became king. It is thought that the Hindu festival of Holī originated from the Prahlādpurī Temple in Multan. (Gazetteer of the Multan District, 1923-24 Sir Edward Maclagan, Punjab (Pakistan). 1926. pp. 276– 77.)

The name Multan is derived from the Sanskrit word “Mūlasthāna,” meaning “the place of origin.” Some believe that it was one of the earliest settlements in the region and may have even been the birthplace of Hindu Dharma. Dr. D.S. Triveda, for instance, proposes that the original home of the Vedic Aryans, who considered the Sapta-Sindhu their home, was near the Devikā River in Multan. This is not a consensus view, however.

Another version of the city’s origin story involves King Uśīnara of the Ānava (Anu lineage), who divided a kingdom on the eastern border of the Punjab among his five sons. Śibi, one of the sons, eventually became the ruler of Multan. He went on to conquer the entire Punjab region, except for the northwest corner, and established four separate kingdoms through his sons: the Vṛṣadarbhās in Multan, the Sauvīras in Sind, the Kekayas in the districts of Gujarat and Shahpur between the Jhelum and Chenab rivers (the Chaj doab), and the Madrakas, with their capital in Sakala (modern-day Sialkot), in the Lahore division of Punjab. According to the Mahābhārata, Śibi was renowned for his honesty, and a story about his truthfulness and compassion is recorded. The tale recounts how Śibi protected a dove from a hawk that sought to make it its midday meal, offering his own flesh from his thigh as a substitute meal for the hawk.

Multan has also uncovered coins belonging to the Yaudheyas. The Yaudheyas were a powerful and influential republican tribe in the area who claimed to be a warrior clan descended from King Yuddhiṣṭhira of the Pāṇdavas. The warrior-related forms Yodheya and Yaudheya are descended from Yodha. (Majumdar, R. C. (Ed.). (1973). History and culture of the Indian people (Vol. 2). Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.)

Looking up to Sūrya Bhagavān

Multan in antiquity was home to a saṃpradāya dedicated to the Sun God Sūrya, centered around the Multan Sun Temple. The significance of the Sun Temple was such that it was noted by Greek Admiral Skylax during his journey through the region in 515 BCE, as well as by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th century BCE. (R. C. Majumdar, J. N. Chaudhuri, G. S. Sardesai, The History And Culture Of The Indian People (11 Vol. Set), 1977.)

The earliest Hindu text that mentions a Sūrya-worshiping sampradāya is the Sāmba Purāṇa, and the associated legend can also be found in the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa and a twelfth-century inscription in Eastern India. The story says that Sāmba, who was cursed and had become a leper, sought Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s help to restore his youth. Kṛṣṇa told him that only the Sun God Sūrya had the power to do so. Following Ṛṣi Nārada’s advice, Sāmba went to the forests of Mitravan on the banks of Candrabhāga, which was already considered a sacred place for Sūrya worship. There, he propitiated Sūrya and received boons of cure and eternal fame, with the condition that he build Sūrya temples. According to the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa, Sūrya specifically instructed that the temples be installed at the banks of Candrabhāga, where he would reside permanently. The next day, Sāmba received an icon of Sūrya while bathing and established the first Sun Temple in Sāmbapurā. Sāmbapurā is believed to be the same as Multan, and the temple is referred to as the eponymous institution. A different legend suggests that the temple was built by the Hindu king Vikramāditya. This temple is also known as the Ādityanātha temple. (Jain, M. (2019). Flight of Deities and Rebirth of Temples: Episodes from Indian History. Aryan Books International.)

The belief in the divinity of the Sun has been passed down from Vaidika times and is still practiced today by the Saura tradition. Ancient coins and medallions, such as a human bust of the Sun with stamens representing his rays, suggest that Sūrya was a widely worshiped deity as early as the third century BC. Greek writers and Kuṣāna coins featuring the name and image of the Sun attest to Sūrya’s continued popularity in later periods. Sūrya is a prominent figure in Itihāsas, with descriptions of his ornaments and family life, including his wives and children, as well as his various adventures. The Gāyatrī Mantra, one of the most sacred in Hinduism, is dedicated to the Sun. Additionally, the Chaṭh Pooja is a popular religious event in Bihar that involves prayer and fasting in honor of the Sun, has been practiced for centuries and continues to this day, further emphasizing the historical significance of sun worship.

The people of Multan are believed to have been protected from conquest and subjugation by the blessings of Sūrya. Even Alexander’s invasion of the city proved to be his downfall. Legend has it that during the battle for the city, Alexander was struck by a poisoned arrow which eventually led to his illness and death. The exact spot where the arrow hit Alexander can still be seen in the old city, as recorded by the Chinese traveler Xuánzàng during his visit to Multan in 641 AD.

During Xuánzàng’s visit in 641 CE, it was the only Sūrya temple in the region. He wrote: “Very magnificent and profusely decorated. The image of the Sūrya-deva is cast in yellow gold and ornamented with rare gems. Women play their music, light their torches, offer their flowers and perfumes to it. The kings and high families of the five Indies never fail to make their offerings of gems and precious stones. They have founded a house of mercy, in which they provide food and drink, and medicines for the poor and sick, affording succor and sustenance. Men from all countries come here to offer up their prayers; there are always some thousands doing so. On the four sides of the temple are tanks with flowering groves where one can wander about without restraint.” (Li, R. (2006). The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions (W.M. Keck Foundation Series). BDK America.) The records of Xuánzàng and various Arab travelers from the 7th to 8th centuries shed light on the significance of the Multan temple during that time. Expensive aloe-wood, imported from Cambodia, was offered to the Sūrya God at Multan.

So what happened to the Sūrya temple in Multan, considering that it no longer exists? It’s intriguing to consider how a temple of such significant repute, known throughout the subcontinent as a wealthy pilgrimage site, can be erased without a trace, to the point where its exact location is unknown today, and even its memory no longer exists. To understand this, we must look forward to the 7th century CE.

The Arrival of the Arabs: A Temporary Setback

During the 7th century, Multan, which had been ruled by the Rāi and Chacha dynasties for centuries, experienced its first incursion by Muslim armies. Before that, it was a flourishing town with a booming textile industry. Armies led by Al Muhallab ibn Abi Suffrah and Abdool Ruhman Bin Shimur conducted several raids into India, reaching as far as Multan. However, their raids were largely unsuccessful and their progress towards the east was halted. The Arabs were unable to penetrate India through the Khyber Pass, the Bolan Pass, or along the Makran coast. (Asif, M. A. (2016). A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia.)

A few decades later, however, Muhammad ibn Qasim would launch another invasion on behalf of the Arabs, marking a turning point in the history of Multan. Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the governor of Iraq, sent Muhammad ibn Qasim into Sindh and Multan to start the Muslim conquest of India. Hajjaj gave strict instructions to kill anyone belonging to the combatants, arrest their children for hostages, and give protection only to those who convert to Islam. (Derryl N. MacLean, Religion and Society in Arab Sind (Brill, 1989), 37.)

In the early 8th century, the Arab armies invaded Sindh, which had recently ended a period of civil wars and was ruled by Rāja Dahīr. Muhammad ibn Qasim faced strong resistance while conquering Sindh, which took him approximately eight months. He encountered difficulties in several towns, including Alor and Brāhmanābād. During the process, he killed many and enslaved thousands of people. Those who were capable of bearing arms were beheaded, while the rest were put in chains.

The Muslim invaders treated the native population harshly and offered the choice of conversion to Islam or death. (Derryl N. MacLean, Religion and Society in Arab Sind (Brill, 1989), 37.) Brāhmanābād’s residents abandoned the fort out of fear for their lives. However, not all Sindhis were willing to surrender, and the invaders massacred thousands of them. As the religious war continued, it proved impractical to offer all Indians the choice of conversion or death, and an adjustment was made to grant the Hindus the status of People of the Book (Ahl al-kitab). The jizya was demanded from the Hindus and their submission was accepted, with the ultimate goal of converting them to Islam. Hindu temples were considered to be centers of idolatry and were destroyed whenever possible. At Daybul, Muhammad ibn Qasim destroyed a Hindu temple and had the Brāhmins circumcised and converted to Islam. However, seeing their resistance, he ordered all those over 17 to be executed. (Arun Shourie, Harsh Narain, Jay Dubashi, Ram Swarup, and Sita Ram Goel, Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them, vol. 1, A Preliminary Survey (Voice of India, 1990), 264.)

The main cities of southern Sindh, Nehrun and Siwistan, showed the least resistance. The conquest of these cities was facilitated by the lack of loyalty among the Buddhist section of society, superstition among some sections of the population, and weak leadership among the ruling dynasty. Muhammad ibn Qasim began encouraging the locals to surrender, but this irritated Hajjaj who wrote to him and criticized his policies. (B. R. Ambedkar, Thoughts on Pakistan (Thacker and Company Ltd., 1941), 50.)

Following his conquest of Sindh, Muhammad ibn Qasim crossed the Beas and laid siege to the city of Multan for two months, as it was one of the most important trading centers of the Indian subcontinent at the time. However, the city was heavily fortified, and its inhabitants were not willing to lay down their arms so easily. Despite facing a shortage of supplies, the local ruler Rāja Dahīr managed to hold off Muhammad’s army. During the prolonged siege, Muhammad’s army had run out of provisions and was resorting to eating donkeys. Despite the Hindus’ refusal to surrender, a traitor from the city eventually betrayed Multan.

This Multanī informant told Muhammad about an underground canal that provided sustenance to the city. (Flood, Finbarr Barry (2009). Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval “Hindu-Muslim” Encounter) Taking advantage of this information, Muhammad had the canal blocked, which led to the surrender of Multan. The able-bodied men were massacred, but the children, women and temple ministers, numbering 6,000, were taken captive. The Muslim invaders discovered a treasure of gold in a chamber that was ten cubits long and eight cubits wide and took it home. Muhammad ibn Qasim infamously looted and transported to Basra 330 chests of treasure, including 13,300 pounds of gold, from the Adityanath temple. The city became known as the “City of Gold” or the “Frontiers of Gold” among Arab geographers until the 14th century due to the acquisition of wealth, either through looting or revenue.

In the 9th century, Aḥmad Ibn Yahya Ibn Jabir Al Biladuri wrote in his work Futuhu al-Buldan about the Arab conquest of Multan and how they acquired a substantial amount of gold from the temple’s halls. He writes, “The Musulmans found there much gold in a chamber 10 cubits long by 8 cubits broad, and there was an aperture above, through which the gold was poured into the chamber.”

Despite the conquest, most of the city’s population remained non-Muslim and resisted conversion for several decades under Umayyad rule. After this initial victory, the Arabs struggled to maintain control, and in a short amount of time, much of Sindh was lost. They were eventually limited to the small states of Brāhmanābād and Multan in the 9th and 10th centuries. That is all the Arabs had to show for three centuries of relentless effort. This limited success, compared to their conquests in the Middle East, Europe, and Persia, was due to the superior military strength and political organization of the Indians.

The Arab conquest of Sindh was not due to their superior military might, but rather, it was their only successful campaign on Indian soil. After their conquest, they faced defeats in conflicts with powerful Indian states. For instance, one Arab army sent to invade North India suffered a major defeat at the hands of Nāgabhaṭṭa I of the Imperial Pratihāra dynasty that was ruling the region then, while another army that entered Lata in South Gujarat was defeated by Pulakeśina Avanijanāśraya in a battle near Navsari.

An Emirate, and a Site of Blackmail

After Muhammad ibn Qasim’s conquest, Multan was ruled by Muslims, but it functioned as an independent state known as the Emirate of Multan from 855 AD. The 10th-century Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi noted that the Multan Sun Temple was in a bustling area of the city, between the ivory and coppersmith bazaars (Shourie et al., Hindu Temples.). The temple was a major source of revenue for the Muslim rulers, drawing large numbers of pilgrims and contributing up to 30% of the state’s revenue. They allowed the temple to exist but hung a piece of cow’s flesh on the deity’s neck in order to humiliate the Hindus to whom the cow was sacred (Shourie et al., Hindu Temples.).

Al-Biruni in his book Kitab al-Hind described the temple’s deity as a wooden statue covered in red leather and with two red rubies for eyes, and even stated that it was built during the Krita Yuga. Abu Rihan relates that the temple and the statue of the Sun, which existed before his time, were said by the people to be 216,432 years old.

In addition to being a major source of revenue for the Arab state, the mūrti of Adityanāth in Multan was also used as a defensive measure. Whenever Hindu Rajas attacked to reclaim the city, the Arabs would display the revered deity on the fort wall and threaten to break it. The Pratihāras were influential in North Indian politics at the time and served as a barrier against the Muslims in the Sindhu valley. Muslim writers believed the Pratihāras were the greatest enemies of the Muslims and could easily defeat them. Al-Masudi writes, “When the unbelievers march against Multan and the faithful do not feel themselves strong enough to oppose them, they threaten to break their idol and their enemies immediately withdraw.” Istakhri, who makes a similar statement, adds that “otherwise the Indians would have destroyed Multan.” (Majumdar, R. C. (1956). Arab invasion of India. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.)

The Muslims leveraged the Hindu Pratihāras religious beliefs to avoid destruction. It seems that the Pratihāras were not fully aware of the Muslim threat, as they let their religious beliefs stop them from defeating the Muslim rule in India, which they had the ability to do. The Hindu leaders of the Pratihāras and Shāhi dynasties failed to act against the Muslim conquerors due to their lack of foresight, statesmanship, and rationality. They could have easily conquered Multan and defended India against the danger of Muslim invasion, but either they were ignorant of the political situation or too parochial in their thinking. The lack of knowledge of the outside world or failure to understand contemporary events, of the kind of societal storm that Islamic rule was, was the main cause of their indifference to the danger that eventually overwhelmed them.

The Rāṣṭrakūṭas (who ruled over large parts of the Deccan at the time), however, took a different approach and befriended the Muslims, giving them opportunities to settle in their territory, build mosques, and be governed by their own governors. This attitude of religious tolerance was uncommon in the world at that time and showed a stark contrast to the destructiveness of the Muslim invaders.

Multan was later captured by the Qarmatian chief, Jalem, the son of Shaiban, when the priests of the Sun Temple were massacred, the deity was broken to pieces, and the temple itself was turned into a mosque. (Shourie et al., Hindu Temples.)

Slipping Away: The Slow Retreat of Dharma

In the early 11th century, Multan was attacked twice by Mahmud of Ghazni. Later, it is believed that a mosque known as Jami Masjid was constructed on the same site as the temple. A single traitor had initiated this entire sequence of events.

The Sun Temple and its deity were however soon restored by the religious zeal of the Hindus. When Al Idrisi of Morocco wrote about Multan in 1130 AD, the worship of the Sun God was as flourishing as ever. The extract from Nuzhat al Musthak of Al Idrisi reads, “Multan is close upon India; some authors indeed, place it in that country. It equals Brāhmanābād in size and is called the house of gold. There is an idol here, which is highly venerated by the Indians, who come on pilgrimages to visit it from the most distant parts of the country, and make offerings of valuables, ornaments, and immense quantities of perfumes. This idol is surrounded by its servants and slaves, who feed and dress upon the produce of these rich offerings.

It is in the human form with four sides and is sitting upon a seat made of bricks and plaster. It is entirely covered with a skin like red Morocco leather, so that only the eyes are visible. Some maintain that the interior is made of wood, but others deny this. However it may be, the body is entirely covered. The eyes are formed of precious stones, and upon its head there is a golden crown set with jewels. It is, as we have said, square, and its arms, below the elbows, seem to be four in number. The temple of this idol is situated in the middle of Multan, in the most frequented bazaar. It is a dome-shaped building. The upper part of the dome is gilded, and the dome and the gates are of great solidity. The columns are very lofty and the walls colored. Around the dome are the dwellings of the attendants of the idol, and of those who live upon the produce of that worship of which it is the object.” (Elliot, H. M. (1867). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians (Vol. 1).)

In 1175, Muhammad of Ghor captured Multan and in 1178, he attempted to invade the Chālukya Kingdom. He sent his envoy to the court of Prithviraj Chauhan to persuade him to come to a peaceful agreement, but Prithviraj refused and Muhammad of Ghor decided to invade his Chāhamāna kingdom. The first battle of Tarain was fought in the winter of 1191 CE, where the Ghurid army was defeated by Prithviraj , who was accompanied by other rulers. Muhammad of Ghor was wounded in the battle, but he retreated and left a garrison at Tabarhindah. Prithviraj Chauhān captured the fort, but did not pursue the Ghurid army. According to the Hammira Mahākāvya, Prithviraj even captured Muhammad of Ghor in the battle but later freed him and let him return to Multan. This proved to be his undoing years later. In 1192, Muhammad of Ghor invaded again, and the second battle of Tarain was fought, ending in a decisive victory for the Ghurids.

The Battle of Tarain is considered a turning point in medieval Indian history as it resulted in the temporary downfall of Rajput power and the establishment of Muslim rule in Northern India, leading to the formation of the Delhi Sultanate.

Multan went on to be ruled by various empires, including the Mamluks and the Tughlaqs. The countryside surrounding Multan was reported to have experienced significant devastation due to the overly high taxes imposed during the rule of Muhammad Tughlaq. Even the Mongols laid siege to Multan at one point. In 1445, it became the capital of the Langah Sultanate and was later conquered by the Mogul Empire in 1526. Under the leadership of the Mogul Akbar, Multan was made into one of the largest provinces of the Mogul Empire.

Saqa Mustad Khan, a Muslim historian, compiled a comprehensive record of Aurangzeb’s military activities using the emperor’s state archives shortly after Aurangzeb’s death in 1707. Benāres, Nādia, Mithilā, Mathurā, Tirhut, Pratiṣṭhāna, Karhaḍa, Ṭhaṭṭā, Multan and Sirhind were the famous seats of Hindu learning at the time. (Roy, S. K. (2018). Education system in India during the Mughals. Research Review International Journal of Multidisciplinary, 3(9), 109.) Multan was famous as a center of specialization in astronomy, astrology, mathematics and medicine.

Khan wrote, “In 1669, the Lord Cherisher of the Faith learnt that in the provinces of Ṭhaṭṭā, Multan, and especially at Benāres, the Brāhmaṇa disbelievers used to teach their false books in their established schools, and that admirers and students both Hindu and Muslim, used to come from great distances to these misguided men in order to acquire this vile learning. His Majesty, eager to establish Islam, issued orders to the governors of all the provinces to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels and with the utmost urgency put down the teaching and the public practice of the religion of these misbelievers.” (Shourie et al., Hindu Temples, 279; Goel, The Story of Islamic Imperialism in India, 280.)

In 1666, Jean de Thévenot visited Multan during Aurangzeb’s reign and described a Hindu temple that attracted pilgrims from far and wide, whose offerings contributed to the provincial treasury. He writes, “At Multan there is another fort of Gentiles, whom they call Catry. That town is properly their country, and from thence they spread all over the Indies; but we shall treat of them when we come to speak of the other sects: both the two have in Multan, a Pagod of great consideration, because of the affluence of the people, that came there to perform their devotion after their way; and from all places of Multan, Lahore and other countries, they come thither in pilgrimage. I know not the name of the idol that is worshiped there; the face of it is black, and it is clothed in red leather; it has two pearls in place of eyes; and the Emir or Governor of the country, takes the offerings that are presented to it.” (Thévenot, J. (1687). Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant (English translation: Travels into Diverse Parts of Asia and Africa). Printed for H. Bonwicke, T. Goodwin, M. Wotton, S. Manship, and J. Nicholson.) The description of the idol was similar to that of Istakhri’s description of the Multan Sun Temple, though Thévenot claimed ignorance about the deity’s identity. Al-Idrīsī’s claim that the Sun Temple had been restored was thus corroborated.

In 1853, Alexander Cunningham visited Multan and noted a local tradition blaming Aurangzeb for destroying the temple, though no one could identify its location. There are also contemporary accounts from earlier centuries that corroborate that the Sun Temple again regained its eminence as one of the most important Hindu places of pilgrimage. It is believed to have continued so until it suffered its final destruction at the hands of Aurangzeb in 1666. Cunningham was told that when the Sikhs occupied the town in 1818, they couldn’t find the remains of the temple and converted a venerated tomb into a Gurdwara. Based on etymological arguments, Cunningham believed the recently destroyed Jāmiʿ Masjid to be the most probable site of the temple. (Cunningham, A. (1873). Report for the Year 1872-73. Archaeological Survey of India.) Notably, a stone image of Sūrya was found at the location and is currently kept in an English museum. (Jain, M. (2019). Flight of Deities and Rebirth of Temples: Episodes from Indian History. Aryan Books International.)

An Afghan incursion, a Sikh fightback

Despite repeated invasions, Multan remained northwest India’s premier commercial center throughout most of the 18th century. In the realm of commerce and trade, Hindu merchants still dominated, with merchants from Multan being particularly renowned for their expansive business dealings and abundant wealth. They were frequently sought after by nobles and the bourgeoisie for financial assistance in times of need.

In the following years, it was ruled by the Durrani empire before finally being conquered by the Sikh Empire in 1818. The siege of Multan, as part of the Afghan-Sikh Wars, took place from March to June of 1818, resulting in the capture of Multan by the Sikh Empire from the Durranis. It was the first time in over a millennium that Multan was liberated from Muslim rule, except for the brief period between 1758 and 1760 when the Marathas under Raghunathrao had seized Multan. At the time of the Sikh conquest, its population was still slightly more than half Hindu or Sikh.

In the past, the Sikh Empire had launched multiple assaults on Multan, with the most significant one occurring in 1810. Despite their victories against the defending forces, the governor of Multan, Muzaffar Khan Sadozai, would retreat into the Multan Fort. In previous sieges, the Sikhs accepted large one-time payments of tribute, while the 1810 attack resulted in Multan being required to pay an annual tribute.

In early 1818, the Sikh Empire’s leader, Mahārāja Ranjit Singh, dispatched Misr Diwan Chand to the southwest frontier of the empire to prepare for an invasion of Multan. By January, a robust supply chain was established from the capital, Lahore, to Multan, using boats to transport supplies across the Jhelum, Chenab, and Ravi rivers. Rani Raj Kaur, the consort of Ranjit Singh, was tasked with overseeing the provision of food and ammunition, and ensured the steady flow of grain, horses, and ammunition to Kot Kamalia, a town located between Multan and Lahore.

Misr Diwan Chand launched the campaign in early January by capturing the forts of Nawab Muzaffar Khan at Muzaffargarh and Khangarh. In February, the Sikh forces, led by Misr Diwan Chand and nominally under Kharak Singh, arrived at Multan and demanded that Muzaffar pay the outstanding tribute and surrender the fort. However, Muzaffar refused, and a battle ensued, with the Sikh forces emerging victorious. Despite this, Muzaffar retreated into the fort, and the Sikh army requested additional artillery. Ranjit Singh responded by sending the powerful Zamzama and other artillery pieces, which began bombarding the fort’s walls. Muzaffar and his sons attempted to defend the fort but were killed in the subsequent battle. The successful siege of Multan marked the end of significant Afghan presence in the Peshawar region and eventually led to a series of events that ended in the capture of Peshawar by the Sikhs. When the Sikhs took possession of Multan, there was not a trace left of the old Sūrya Temple. Enraged by this, they turned the tomb of Shams-i-Tabrez into a hall for the reading of the Granth.

After this, Multan came under the control of a Hindu vassal, Dewan Mulraj Chopra. In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War broke out, and was won by the British East India Company. Three years of uneasy peace were spent trying to keep Multan practically independent under Mulraj while ostensibly under the control of the East India Company.

Multan had 80,000 residents in 1848. It was renowned for its richness and served as the regional trading hub for spices, silks and other treasures. Early in 1848, Sir Frederick Currie, the newly appointed Commissioner in the Punjab, asked that Mulraj pay back taxes and levies that had been owed to the Sikh Empire’s central Durbar. Mulraj abdicated in favor of his son in an effort to prevent a full annexation of Multan. Nonetheless, Currie made the decision to install Sardar Khan Singh as the Sikh monarch, who would be accompanied by Patrick Vans Agnew, a British political agent. (Charles Allen, Soldier Sahibs, Abacus, 2001)

In April 1848, the two British officers, Vans Agnew and Lieutenant Anderson, arrived in Multan to take control of the citadel from Mulraj. They were attacked by Mulraj’s troops and both officers were killed. Mulraj saw himself as committed to rebellion and presented Vans Agnew’s head to the local authorities. The British political agent in Bannu, Lieutenant Edwardes, took steps to suppress the rebellion but was hindered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Bengal Army, Sir Hugh Gough, who did not want to expose European troops to a campaign during the harsh weather. In June, Edwardes led an army against Multan and defeated Mulraj’s forces. General Whish was ordered to begin the siege of Multan, but the East India Company’s forces were too weak to maintain it and were forced to retreat.

Sher Singh Attariwalla, a detachment of the Khalsa, rebelled against the East India Company in September, leaving the siege vulnerable. The Sikh Khalsa Army, under the command of General Sher Singh, inflicted a significant defeat on the British Army at the Battle of Chillianwala. Both sides claimed victory, but the Sikhs were eventually seen as the victors. This was one of the toughest battles fought by the British Army and led to the loss of British prestige, contributing to the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

In November, General Whish was reinforced by a large force from the East India Company’s Bombay Army and was able to easily supply the large force. Inside the city, Mulraj had 12,000 troops and 54 guns.

Whish ordered four columns of troops to attack the suburbs of a city. The attack resulted in Mulraj’s forces being driven back into the city and the city walls being breached. The main magazine in the citadel exploded, killing 800 of the defenders, but Mulraj maintained his fire. Whish ordered a general assault on January 2, 1849, leading to a bloody house-to-house fight in the city. The Nawab of Bahawalpur was a key ally of the British in this endeavor. Whish ordered civilians to be herded into the main square, resulting in further casualties. The citadel held out for another fortnight, but eventually fell on 22 January after heavy bombardment and an explosion of three mines under its walls. Mulraj surrendered with 550 men, but only after Whish insisted on unconditional surrender. It then fell to the British Empire and became part of British Punjab.

Corporal John Ryder of the (European) Bombay Fusiliers later wrote of the city after the siege, “Mountains of dead lay in every part of the town, and heaps of human ashes in every square, where the bodies had been burnt as they were killed. Some were only half-consumed. Many had been gnawed and pulled to pieces by dogs; and arms, legs, heads and other parts lay in every place. The town swarmed with millions of flies.” (Ian Hernon, Britain’s forgotten wars, Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2003)

The British acquired significant amounts of plunder. The value of Mulraj’s treasury was estimated to be three million pounds, a substantial amount for the era. The already damaged castle was further destroyed and washed away after a massive overflow of the Indus and Chenab rivers in August of 1849, and it eventually turned into an island of muck in the middle of the floodwaters.

After the establishment of British control in Punjab, the British were worried that a strong leader like Sher Singh Attariwalla could spark a large-scale conflict with them again, so they exiled him. The fall of Multan was a key event in consolidating British rule in India for a century afterwards.

Role in the freedom struggle

Surendra Nath Banerjee, a pioneer in demanding full independence from British rule, founded the Indian Association as a forum for discussing national matters. He embarked on a nationwide tour with the aim of fostering a robust public sentiment, unifying India’s diverse communities based on shared political goals and aspirations, promoting goodwill between Hindus and Muslims, and engaging the masses in the key public movements of the time. Multan was one of the key stops on his tour.

Henry Cotton, a member of the Indian Civil Service (ICS), but sympathetic to the political aspirations of India, describes his impression at the time: “The educated classes are the voice and brain of the country. The Bengalee Babus now rule public opinion from Peshawar to Chittagong; and, although the natives of North-Western India are immeasurably behind those of Bengal in education and in their sense of political independence, they are gradually becoming as amenable as their brethren of the lower provinces to intellectual control and guidance. A quarter of a century ago there was no trace of this: the idea of any Bengalee influence in the Punjab would have been a conception incredible to Lord Lawrence, to a Montgomery, or a Macleod, yet it is the case that during the past year the tour of a Bengalee lecturer, lecturing in English in Upper India, assumed the character of a triumphal progress; and at the present moment the name of Surendra Nath Banerjee excites as much enthusiasm among the rising generation of Multan as in Dacca”. (Mittal, S. C. (1977). Freedom Movement in Punjab, 1905-29. Concept Publishing Company.)

The tour of Surendra Nath Banerjee brought a wave of hope and inspiration to the Indian community. It showed that politics could be just as captivating as religion and that there was a greater unity and shared interests among the different regions of India than previously believed. This realization paved the way for the creation of a nationwide political organization within a decade. The tour also proved that it was possible to unite the masses under a common political goal to improve India’s political condition.

By 1907, Multan had become one of the sites of political agitation in favor of home rule in Punjab along with Lahore, Amritsar, and Ferozepore. Nationalist factions advocated for the assassination of high-ranking British officials, as well as calling upon the public to revolt and overthrow English rule. In addition to this, an active effort was launched to turn the yeomanry, a primary source of recruitment for the armed forces, against the British. This was done through the spread of seditious literature and public meetings where the attendees, many of whom were military pensioners, were openly encouraged to join the cause of rebellion.

The Demographic balance shifts

During colonial times, Multan’s industrial potential went largely untapped due to the British building only a few railway lines, as well as the unequal distribution of canal colonies. This led to high unemployment and low wages, which was exacerbated by the alteration of the land by the government. (Ahmad, A. N. (2022). Infrastructure, Development, and Displacement in Pakistan’s “Southern Punjab”. Antipode.) As a result, many people decided to voluntarily leave Multan. Furthermore, communal riots in the 1920s and the violent actions of Muslim attackers against the Hindus, which included plundering, massacres, and dishonoring of women, shocked the nation and caused many Hindus to flee Multan. **These two factors, along with the differential in fertility rates between the communities, combined to result in a Muslim majority in Multan during British rule.

The Hindu Mahasabha came into prominence with an active program by way of reaction to the horrible atrocities perpetrated by Muslim aggressors on Hindus in Multan, Malabar and other places where rioting had taken place. Madan Mohan Malaviya advocated for the formation of Hindu Sangathan in order to promote the interests of the Hindu samāj.