Recently, we’ve seen some heated debates in parliament around Vande Mataram and electoral issues, a visit from Russian President Vladimir Putin, and a vicious online campaign against critics of the film Dhurandhar. Jahnavi Sen is joined by lawyer Shahrukh Alam and The Wire’s political editor Ajoy Ashirwad Mahaprashasta to discuss all of this.

Dhurandhar showcases Bollywood’s New Obsession: The Sexy Pakistani Villain

We watched Dhurandhar last night at Apple Cinemas (the last time we went to see Ishaan Khatter’s Homebound). It is the best mass-market Bollywood film I’ve seen since Animal, and far more immersive. What struck me most was not the action, nor the plot, but Bollywood’s new formula: a full-scale fetishisation of Pakistan.

Kabir keeps claiming that Bollywood casts Pakistanis as villains. This misses the point. The villain is always the sexiest figure in any film. Bollywood has finally realised this. Raazi hinted at it. Animal stumbled on it with Bobby Deol’s star stealing turn. Dhurandhar perfects it.

For the first time, Hindu actors are not performing cartoon versions of Pakistan. They are cosplaying Pakistanis with forensic precision; the clothes, the diction, the swagger, the social codes. In earlier decades the attempt was clumsy. Now the calibration is exact. Pakistan, in these films, becomes the Wild West of the subcontinent: familiar enough to feel intimate, distant enough to feel dangerous. Continue reading Dhurandhar showcases Bollywood’s New Obsession: The Sexy Pakistani Villain

Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s Powerfully Insightful JNU Lecture on “Reflections on Global Political Thought”

This video presents an extraordinary intellectual experience with this powerful lecture delivered by Pratap Bhanu Mehta — Senior Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research and Lawrence S. Rockefeller Distinguished Professor, Princeton University. Recorded by me (Samim Asgor Ali, the owner of this YouTube Channel) on Monday, 1st December at 3:30 PM in the SSS-1 Committee Room, JNU, under the banner of the JNU Lecture Series, this talk titled “Reflections on Global Political Thought” dives deep into some of the most urgent questions shaping our world today — The global crisis of ideas reshaping modern political landscapes, how shifting political imaginations influence democracy and governance, the profound dilemmas of contemporary political theory, why global political thought must reinvent itself for a radically changing world.

When was India’s Golden Age?

When people claim that India and Pakistan are “equally artificial,” they erase the long, uneven civilisational trajectories that produced both. Kabir, who is generally more courteous than the average Saffroniate imagines, still falls into this conceptual trap. But the question this raises is larger than contemporary geopolitics:

When was India’s Golden Age, and for whom?

A Golden Age can be political, cultural, philosophical, or civilisational. The answer depends on what we measure: scale, radiance, confidence, or continuity. Asking it forces us to examine whether India is a recent invention or a very old organism repeatedly broken and reconstituted.

Pakistan complicates this picture. As the Indus zone, it has deep civilisational roots of its own; older than Islam, perhaps as a geographic expression even older than the Vedic world. This is why, despite its ideological volatility, Pakistan will likely persist: it sits on a basin that has generated coherent cultures for five millennia. Its anti-India posture gives it political definition, but its underlying geography gives it durability. Continue reading When was India’s Golden Age?

What does it feel like to be a Muslim in Modi’s India? Have they become second class citizens?

In the context of X.T.M’s post “Who can speak for the ‘Muslim minority’ of India?” , this video is extremely relevant.

I am often accused on BP of having an “anti-Indian” agenda when I state facts such as that the BJP doesn’t have a single elected Muslim parliamentarian. Yet, these are the exact same arguments being made by Najeeb Jung, who has been the Lt. Governor of Delhi and the Vice Chancellor of Jamia Milia Islamia and thus is not at all a Pakistani.

Today we focus on questions that few people are likely to address yet they are important and need to be honestly answered. What does it feel like to be a Muslim in Modi’s India? How do Muslims feel when they are lynched in the name of cow protection, accused of love jihad, hear calls to boycott their businesses, pilloried in campaign speeches and told to go to Pakistan? Does this suggest that Muslims are becoming second class citizens in India? As a result has the fraternity that binds India’s communities been fractured and weakened? And what is the Prime Minister’s response to this?

Where Do Brahmins Come From?

The Historical, Genetic, and Mythic Answer

The idea that “all Brahmins come from Kannauj” is neat, flattering, and wrong. Kannauj is one important node in a much older, wider story. Brahmins do not descend from a single tribe or city. But they do share ancestry. That ancestry is older than Kannauj, older than caste, and visible in both texts and genes. To understand it, we must keep two truths in view at once: Brahmins have many regional origins, yet they descend—paternally—from a small circle of Vedic founders whose lineages spread across India.

This is the cleanest way to explain it without euphemism or ideology.

1. What the Kannauj Narrative Actually Refers To

When groups claim origin from Kānyakubja (Kannauj), they refer to the medieval centre that produced, housed, and exported Brahmins—especially after the Ghaznavid and Ghurid invasions pushed scribal and priestly families south and west. These migrants seeded communities in Maharashtra, Gujarat, the Konkan, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra. Their prestige shaped memory: “coming from Kannauj” became a shorthand for ritual pedigree. But Kannauj was only one centre among many. It cannot explain the full map of Brahmin origins.

2. The Real Landscape: Many Independent Lineages Continue reading Where Do Brahmins Come From?

Has Indian democracy entered a one-party era? Pratap Bhanu Mehta explains|SpeakEasy-Episode 2

In the second episode of Frontline’s SpeakEasy, independent journalist Amit Baruah speaks with political scientist Pratap Bhanu Mehta about the future of Indian democracy and the global turn towards strongman politics. Mehta examines whether India is drifting toward one-party dominance, why Hindutva has become the ideological centre of gravity, and how political fragmentation, weakened institutions, and a fading opposition have reshaped the democratic landscape. He warns that India’s constitutional norms are being stretched to “infinite elasticity”, that authoritarian trends are deepening, and that the ruling elite may no longer find it easy to relinquish power if pushed into opposition. From the collapse of AAP’s political promise to the Congress’s leadership crisis, from institutional capture to the dangers of partisan citizenship, Mehta draws parallels between India and other democracies sliding toward executive overreach—including the United States and France.

Who can speak for the “Muslim minority” of India?

Public debates on Indian Muslims often make one basic mistake: they collapse all minorities into a single category and then declare that “everyone is thriving because a few individuals have done well”. This flattens history, erases structure, and turns civilisational questions into census arithmetic.

1. Minorities Are Not Interchangeable

Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists offer no meaningful analogy to Indian Muslims.

-

Jains were never politically central to the subcontinent.

-

Sikhs built a regional power, not a pan-subcontinental order.

-

Buddhists have been demographically marginal for a thousand years.

Indian Muslims were different. For centuries they formed the civilisational elite of North India; shaping courts, languages, music, etiquette, food, architecture, and the ways Indian states understood power. Delhi, Agra, Lucknow, Hyderabad were not enclaves. They were the centre of the political and aesthetic world of the Indo-Gangetic plain. A fall from centrality is not comparable to never having been central at all.

2. Individual Success Is Not Structural Health Continue reading Who can speak for the “Muslim minority” of India?

Cyclone Ditwah November 2025

Cyclone Ditwah may have been a once in a 1,000 year event. However the Oceanographic and Atmospheric Physics implies this could be in all probability a regular even, may be a once in 10 years event.

First, energy for cyclones comes fir the ocean. Usually sea surface temperatures higher then 27 degrees is required. The ocean around Sri Lanka is currently more than 30 degrees. More than sufficient energy.

Second, more importantly the formation history of TC Ditwah. This is from the analysis of Dr Sarath Wijeratne.The system started with the formation of two low pressure systems: one to the south-east of the Island and the other south-west. The one to the south-west was stronger and moved to the east whist the one south-east moved slowly to the west. Ultimately they joined together to form TC Ditwah. This merging of two low pressure system is called the Fujiwhara effect. This very rare event and has not been documented in this region. The merging of the two low pressure systems intensified TC Ditwah. Now we know the result. (Charitha Pattiarachi)

Watch video

https://web.facebook.com/511554041/videos/pcb.10164281956204042/828565176728130

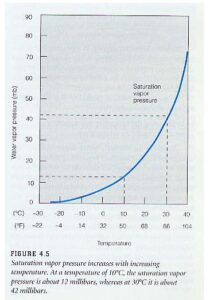

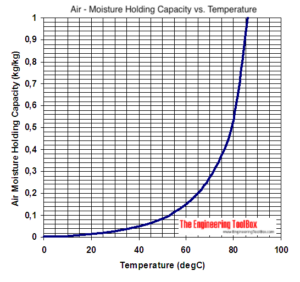

There are two basic Physics that make the current condition conducive to devastating storms

a) Evaporation becomes exponential around 30C

b) Water holding capacity of Atmosphere too turns exponential around 30C

Thus a small change in air temperature results in a large change in amount of water vapor that can be held in the Atmosphere

The larger the amount of water held in the atmosphere, bigger possibility of it condensing i.e. becoming rain. Worse because bigger amounts, it will come down in buckets,

Increases in atmospheric water vapor also amplify the global water cycle. They contribute to making wet regions wetter and dry regions drier. The more water vapor that air contains, the more energy it holds. This energy fuels intense storms, particularly over land. This results in more extreme weather events. (This was known by Year 2000 from Climate Models) For South Asia means wetter Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka. Drier North India.

Nehru bashing has become very old but is it ineffective yet ?

Priyanka Gandhi Vadra targeted PM Modi over the latter’s repeated Nehru bashing, and i felt a some happiness that someone was voicing what i had felt for 6 odd years now, and done so in a rhetorically effective way (unlike her brother).

“When Done Nehru Bashing, Debate Unemployment”: Priyanka Gandhi’s Top Quotes

You can find the entire speech on YouTube : LIVE: Smt. Priyanka Gandhi ji speaks in Parliament on the 150th anniversary of ‘Vande Mataram’.

Ram Guha has said multiple times that if Rahul and Priyanka were to leave the INC, the charge of dynasty and sins Nehru and Indira (real and alleged) wouldn’t pull the INC back as much as it does. But i think we are at a point where even firm BJP supporters are fed up of BJP’s Nehru bashing and its bound to have diminishing returns.

Its been 12 years and Nehru bashing brings cheers from only the hardcore supporters and none others. Maybe we are at an inflection point, maybe not.

Personally I remain an admirer of Nehru while disagreeing with his decisions profoundly. Maybe i will expand upon my criticisms and praise at some point but i do not think Gandhi erred massively in choosing Nehru over Patel. While i do think Gandhi shouldn’t have gone against democratic nature of congress (which had chosen Patel), I do think Nehru would have been a better PM had Patel remained alive longer into Nehru’s term. A bit cliched but Nehru’s life kind of reminds me of famous lines from Dark knight trilogy.

You die a hero or you stay alive long enough to become a villain.

I am not into fortune telling but i think the path Modi is following is very similar to his great opponent (atleast in his own mind), Jawahar Lal Nehru. I think they’re a bit more alike that their followers think. But all thats for another time.